Elo Kiivet revisits Tulbi-Veeriku quarter in Tartu where the friction between these two dimensions has given rise to one of the most praised new neighbourhoods of early noughties in Estonia.

In order to compensate for the bureaucratic inflexibility and sluggishness that is burgeoning in spatial design, a new methodology has evolved that enables to operate in a more democratic, playful, experimental and cost-effective way.

After the slow-burning and partly contestable success stories of Rotermann Quarter and Telliskivi Creative City, the eyes of Tallinners interested in urban design or just longing for a better urban space turned to Noblessner—the privately developed waterfront set to become one of the first chapters on the road to open the coastal areas of Tallinn to its citizens. Though far from complete, the lively quarter already offers a chance for a status report and an insight into the entrenchment of certain spatio-social tendencies in the Estonian real estate landscape.

For three consecutive summers Paide central square has provided a collaborative platform for locals, participants of the Opinion Festival and municipality to find the best possible joint space for the community.

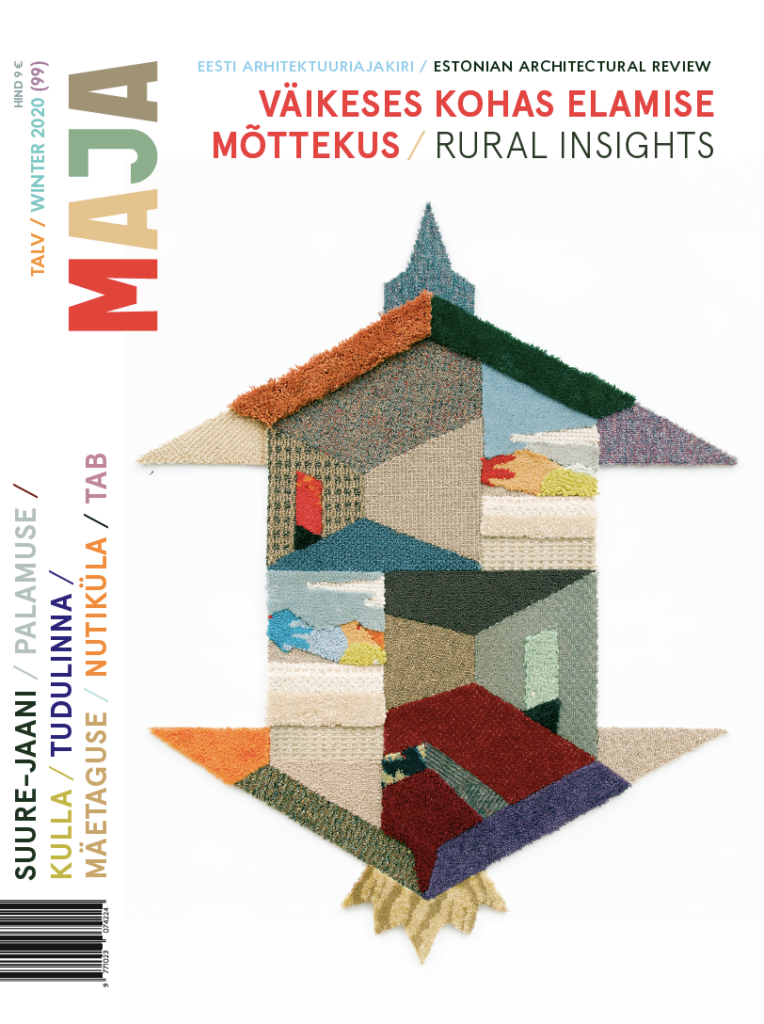

Maja 2020.a. talvenumber on ilmunud!

The monument dedicated to Lydia Koidula and Johann Voldemar Jannsen near the Arch Bridge in Tartu may be discussed primarily in two respects – in terms of sculptures and landscape architecture. The memorial square strives for the human-scale but how successful is it?

In 2007, the city council again approved the concept “Opening Tallinn to the Sea” with one of its aims including a populated urban space. The simultaneous activities – seaside arterial roads and the wire fences obstructing the sea views and the use of the coast, however, were entirely contrary

No more posts