PAIDE STATE SECONDARY SCHOOL

Location: Posti 12, Paide, Estonia

Architecture: Maarja Kask, Ralf Lõoke, Helina Lass, Ragnar Põllukivi, Martin McLean / Salto AB

Interior Architecture: Birgit Palk, Tarmo Piirmets ja Raul Tiitus (OÜ Pink)

Commissioned by: haridus- ja teadusministeerium

Represented by: Riigi Kinnisvara AS

Construction: AS Megaron-E

Total area: historical building 935 m2, extension 1922 m2

Competition: 2019

Project: 2019–2022

Completed: 2022

Paide State Secondary School is an excellent example of the mutually complementary dialogue between a historic space and contemporary architecture. Liina Jänes sheds light on the complex background of the building’s evolution highlighting the multifaceted nature of spatial design.

Paide Secondary School began their work in the new building in December 2021. The school actually operates in both the old and the new building. The architecture competition yielded a solution allowing to add an extension to the historicist school building constructed in 1910 in order to accommodate a contemporary state secondary school. The school is located right below the rampart slope in Paide old town. In the north, there are the ruins of the Order Castle with the rampart tower, bastions and the moat, while the central square with the church and town hall is only 100 metres away. It would be hard to find a location with a more central and liable role in Paide. It is also a heritage conservation area with the protected building arousing strong sentiment in the locals as even in its most miserable condition, the former girls’ school was considered one of the most scenic buildings in the town.

Renovating a building in the town centre and giving it a public function will attract new users to the old town and activate the urban space. Such a building has several roles: it densifies and brings new life to the centre, improves the urban scene and living environment, instils optimism and encourages the reconstruction of neighbouring buildings.

It thus seems surprising that the new building has no problems placing itself in the location entrusted to it, giving new life to the heritage object and invigorating the old town. With the secondary school, Paide not only finally gained a new building featuring contemporary architecture but also the culturally relevant schoolhouse was restored and the old town given a denser use. How can one small building do all that? It was decided to take the opportunity to intervene in the more general urban space by means of one house. Renovating a building in the town centre and giving it a public function will attract new users to the old town and activate the urban space. Such a building has several roles: it densifies and brings new life to the centre, improves the urban scene and living environment, instils optimism and encourages the reconstruction of neighbouring buildings.

Moving a public function into the old town and into an old, abandoned building should not be a feat, however, the decision came only after tedious lobby work1 accompanied by immeasurable disputes and court cases. The story of Paide State Secondary School illustrates the current situation in spatial design in Estonia—there is nobody to manage the whole picture and it is thus nobody’s responsibility. It also highlights the most acute concern of heritage protection at the moment—unused buildings.

Use it or lose it

Empty buildings and the fact that much of the building stock is left unused while new ones are regularly built obviously constitute a broader problem than mere heritage protection. According to statistics, 23.4% of protected buildings are out of use with more than a third (36.5%) in a technically poor condition.2 The statistics about Paide are distorted by the very small number of buildings under heritage protection—the old town is protected as a complete urban environment or heritage protection area. Unfortunately, there are very many unused buildings in the heritage protection areas of small towns. For several reasons. Resettlement of population, demographic development and (the lack of) regional policy are social processes affecting the building stock regardless of the value of the building. These processes cannot be influenced by the means of one field only.

Then again, the development of heritage conservation areas has so far not been in the focus of the cultural heritage policy. During the Soviet years, the shift from the protection of individual objects to valuing environments accompanied by the establishment of the first urban conservation areas was considered highly innovative,3 however, there has been no significant comprehensive development of the given areas in the past thirty years. The daily life of heritage conservation has been beating to the rhythm of individual buildings. Urban development is within the competence and responsibility of local governments, but over the years, the state has failed to resort to some softer means that heritage protection offers: to promote old towns as cosy living environments on human scale, the local heritage as the regional catalyst or simply the reuse and recovery of old houses as part of economical and green thinking. We have seen such renaissance only in so-called milieu areas. It is only in the last decade when shrinkage and empty buildings became part of our daily news that the reuse of buildings has also become a strategic goal in heritage protection with assistance provided in every way by means of solutions, compromises and grants.

The heart of the school in the new building

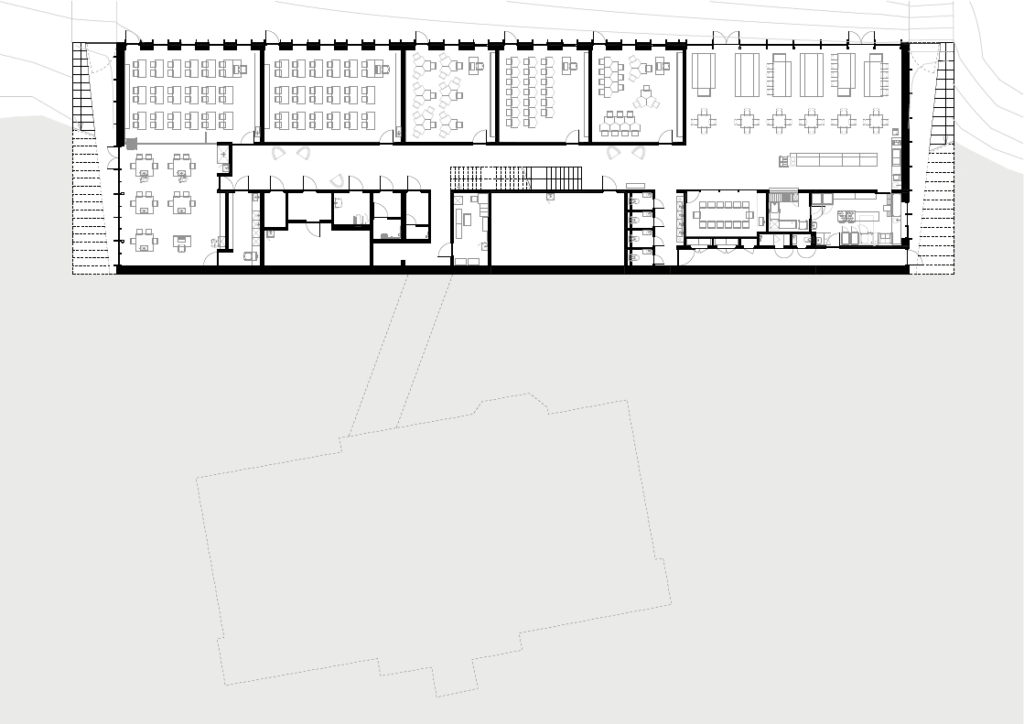

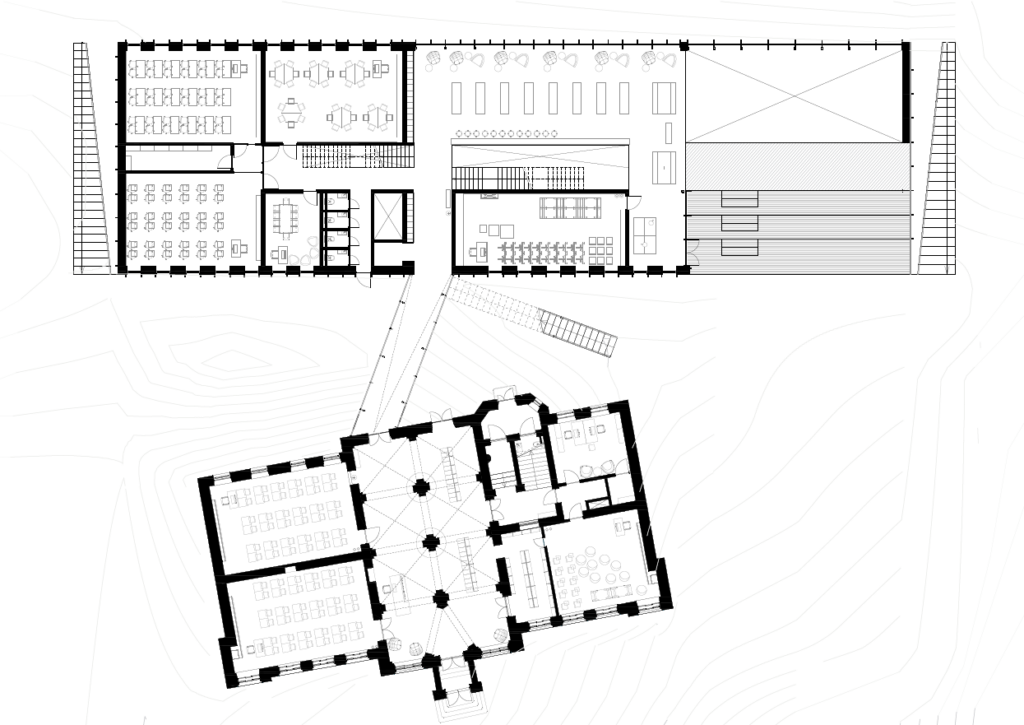

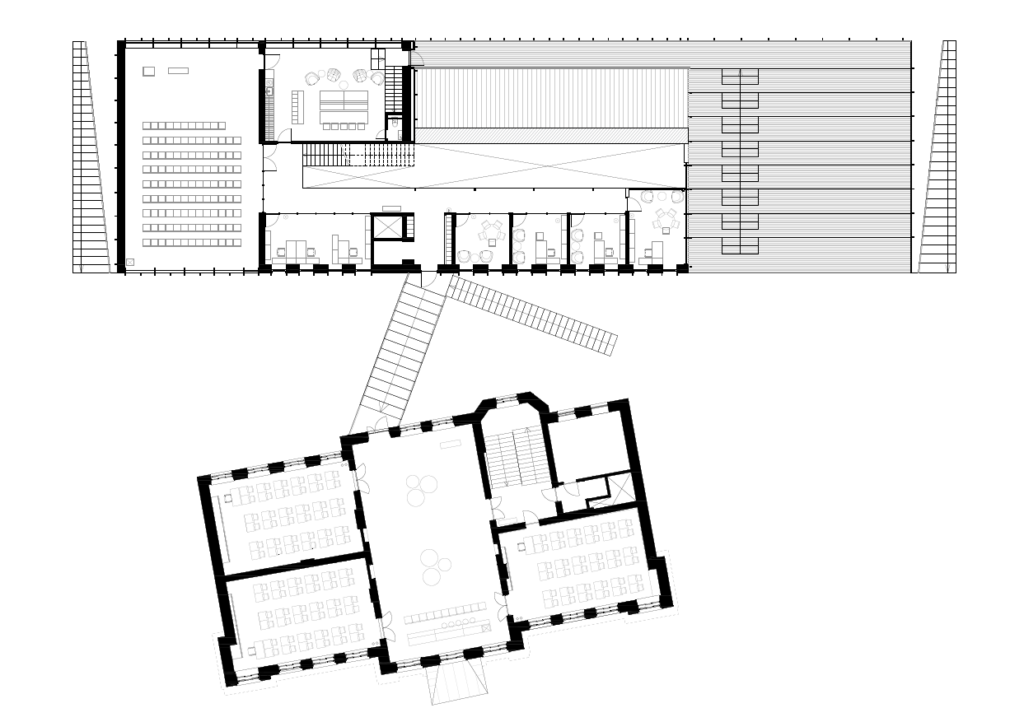

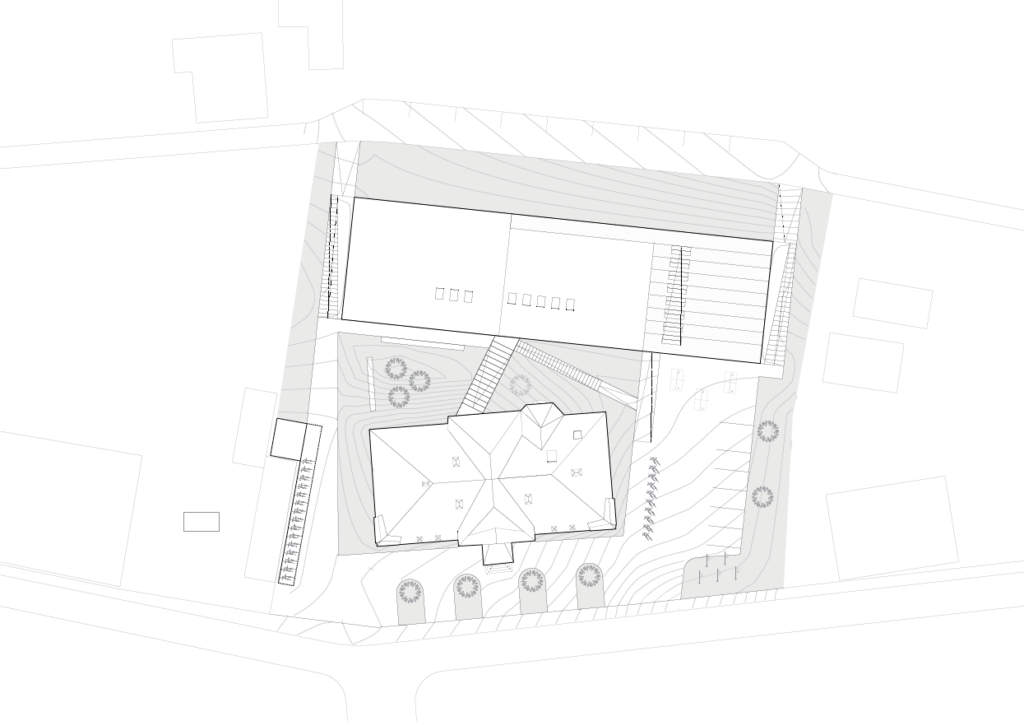

They say the school in Paide with 250 student places is the smallest of all state secondary schools. Although there had been altogether 200 students in the historical girls’ school, they now needed an extension. The combined new and old buildings perfectly fit the urban space. The parts of the building are somewhat offset to each other as one runs along Posti and the other along Valli Street. They are joined by a diagonal gallery.

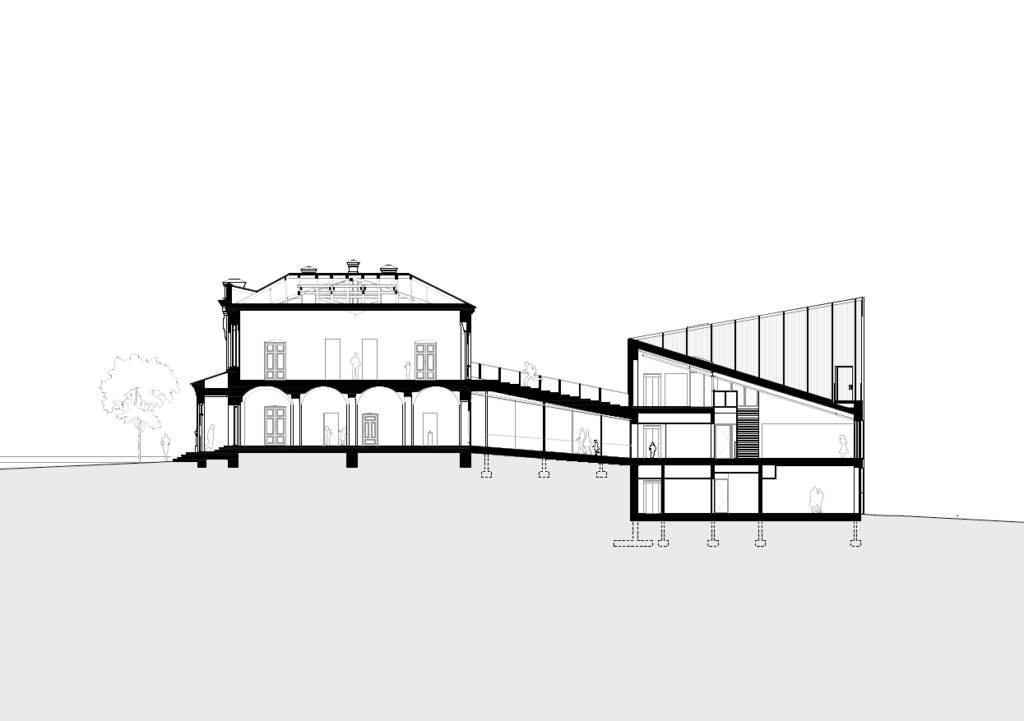

People working and studying at the school consider the new building accommodating most of the common areas as the heart of the school. The entrance is located in the historical building with the high vaulted ceiling in the lobby instilling the importance of tranquillity and traditions while the glass gallery leads you to the new building. The new building is highly inspiring with the accentuated diverse space stretching over various levels and inviting you to move, use it and communicate with its other users. One function transforms seamlessly into another as the spaces can be used for various purposes.

Buildings by Salto Architects are known for their search for and creation of new pathways making you see the well-known places in a different light (considering, for instance, the recently completed cruise terminal in Tallinn). This is the effect also in Paide school where the new extension aligns the entire plot, creates a cosy courtyard area as well as a public connecting path between Posti and Valli Streets. The new building also marks the outer slope of the moat in Valli Street thus giving the former footpath more street-like features. Looking at the competition entries now, it appears that Salto’s solution attempted to keep the extension strictly separate from the historical building. The clear distinction between the old and the new is not always necessary, however, in case of such a vibrant red-brick façade, the new building with a thermally processed pine façade seemes an excellent choice. The distinctly different features of the buildings do not necessarily mean that they cannot communicate or form a comprehensive whole.

Familiar features from Salto’s earlier works are also the connections between the building and the landscape as well as the roof landscape in the form of steps. Ralf Lõoke has said that he attempts to approach school projects from the viewpoint of the natural qualities of the plot.4 If in case of some earlier buildings they needed to create the landscape themselves (for instance, the sports building of Estonian University of Life Sciences), then the plot in Paide already included intriguing features in the relief with the difference in height near the moat reaching up to 5 metres. It allowed the new building to have three floors without overwhelming the historical two-storey building and allowing the latter to be viewed from all sides.

The new building is terraced and consists of three blocks with their roofs alternately rising and falling towards the rampart and Posti Street. The layout is well balanced affording great views both inside and outside the building. Compared to the initial competition entry, the blocks have been turned in the reverse order allowing the steps to be used for outdoor studies as well as for relaxing while keeping an eye contact with the street space. The emergency exit from the teachers’ lounge also leads to the steps that otherwise similarly offer an enviable opportunity for recreation. Below the steps is the canteen, on the same level with Valli Street, communicating with the street space through the windows. The upper block of the new building accommodates the great hall that has benefitted the most from the reversal now affording picturesque views of the rampart tower.

A historical monument and options for heritage conservation

Previously overshadowed by tall trees, the historical building now forms a distinguishing element in the street space. Continuing its use as a school building was definitely the least painful solution in the situation. Abandoned in 2001, it was bought from the town by a private owner in 2004 who had various plans to establish either a hotel with a conference centre or offices and at the peak of the economic boom even apartments, with none of them eventually coming to life. All the plans would have included also complete reconstructions with the high and extensive rooms split by ceilings and partitions. It was only after years of disputes that an agreement was reached on the establishment of Paide State Secondary School in the building and the state bought it back from the private owner.

Today, the protected building does set some restrictions on the contemporary school, for instance, the requirement to preserve the original clear layout, however, they have nevertheless managed to accommodate five classrooms there with no compromises made on modern technology, lighting or ventilation. All contemporary needs have been satisfied and given their place in the historical space.

In the course of the renovation, further murals were discovered in addition to the previously known ones, also confirming the hypothesis that their author was August Roosileht.5 The discovery was made all the more thrilling by the fact that it is an artist originally from Järva Country who remained true to Paide until the end of his life despite studies in the wide world. Although featuring also folk motifs, his murals are generally highly expressive and modern thus adding to the general grandeur of the space. High ceilings, large windows, the rich stuccowork of the great hall, murals and other values of a historical building have formed the basis for the interior architecture conveying a more presentable feel in the given part of the building.

From the point of view of heritage conservation, the approval of the given project was a manifestation of one of the above-mentioned strategic directions with several compromises made in the process. In order to find a function for the abandoned school building, the construction of the extension was approved which, in turn, meant the demolition of the archaeological heritage object—a 16th-century lime kiln—discovered on the site. It was a choice between two values—whether to preserve the earlier history of Paide in situ or document the underground findings and restore the school building from the early 20th century instead. As the school building in the given location also stood for a more compact old town and more dynamic heritage protection area, the latter option was chosen.

It was a choice between two values—whether to preserve the earlier history of Paide in situ or document the underground findings and restore the school building from the early 20th century instead. As the school building in the given location also stood for a more compact old town and more dynamic heritage protection area, the latter option was chosen.

A small house with a great impact

The school has been received well by the locals. One might think that constructing a modern building right next to the Order Castle will not go down easily, however, feedback so far has been unanimously positive. They would like it to be even more open to the locals and correspond to the content of the contemporary school which not only is responsible for school life but functions also as a community centre.

Both teachers and students are happy. According to the headmaster, the space is indeed important, however, what happens in the space is even more important, that is, the relations between teachers and students and their common values—openness, trust and developing a democratic culture of dialogue. The physical space of the school in Paide supports the given values. It seems to me that although it is a new school, it already has a strong identity with the school building playing a considerable role in this.

LIINA JÄNES is an architecture historian and heritage conservation specialist working as a heritage protection adviser at the Ministry of Culture.

HEADER photo by Terje Ugandi

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

SEE ALSO: https://ajakirimaja.ee/en/framework-of-the-paide-process/

1 The selection of the location of Paide Secondary School is discussed by Andro Mänd in his article ‘Framework of the Paide Process’, Maja, Autumn 2021.

2 As of the end of 2021. Source: National register of cultural monuments.

3 The first heritage site was established in Tallinn in 1966, protected areas in small towns, including Paide in 1973.

4 Ingrid Ruudi’s interview with Ralf Lõoke, ‘Ralf Lõoke: On Spatial Quality Beyond Excel’, Maja, Spring 2021.

5 Hilkka Hiiop, ‘August Roosileht ja Paide Gümnaasiumi maalingud’ [transl. ‘August Roosileht and the Murals of Paide Secondary School’], Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2021, (Tallinn: Muinsuskaitseamet, 2022).