What would an architectural journal be without photos to explicate architectural space? Can a photo be more revealing and polyvalent than the architecture it conveys? In an attempt to understand what distinguishes actual space from its photographic counterpart and the role of photography in architecture, I asked architectural photographer Tõnu Tunnel, architect Ott Kadarik, architect-photographer-artist Paco Ulman and artist Paul Kuimet, what makes for a meaningful image.

Tõnu Tunnel is known to the readers of Maja primarily because for several years in a row now, there has probably not been a single issue where his photos would not have been used. His trademark is a resourceful eye for composition and sensing the environment around a building. Not many Estonian architects would hesitate to ask him to capture their work. The images he produces are often better than the architect’s vision of a completed building.

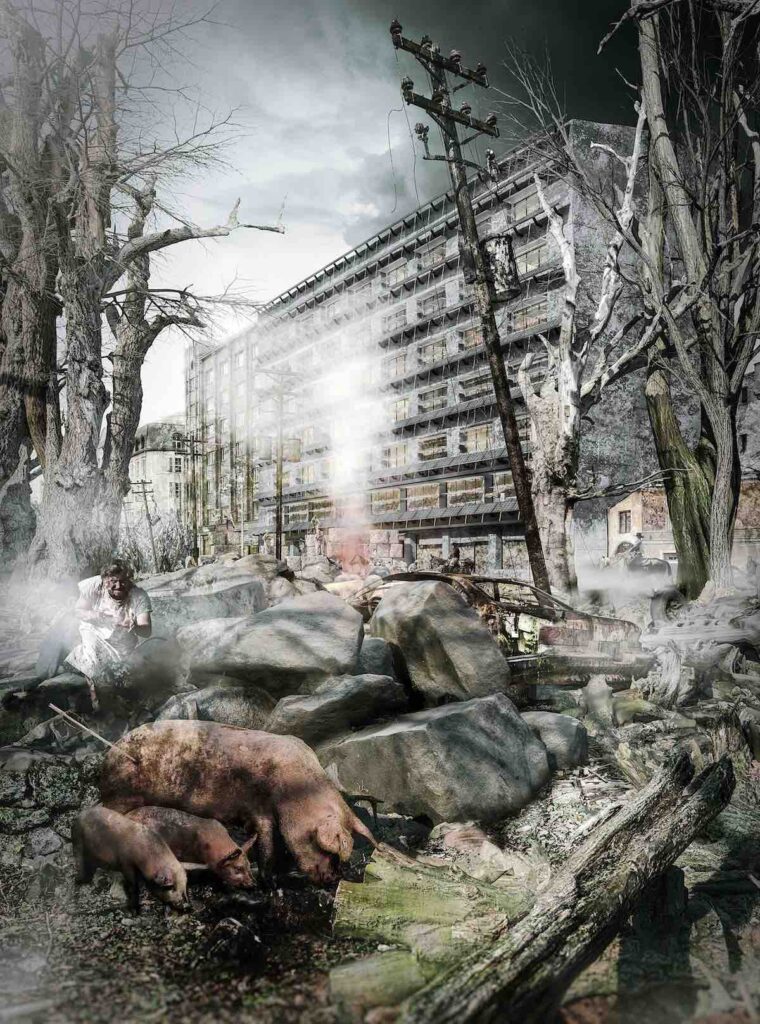

Ott Kadarik is a camera-endowed architect who takes shots of things that interest him and if the lens happens to be missing a fascinating scenario, his creative impulse affords him the ability to create one either by rendering or photo editing. His Instagram account @Kodarik is embellished by shots framed beyond this realm, accompanied by succinct contextualising captions.

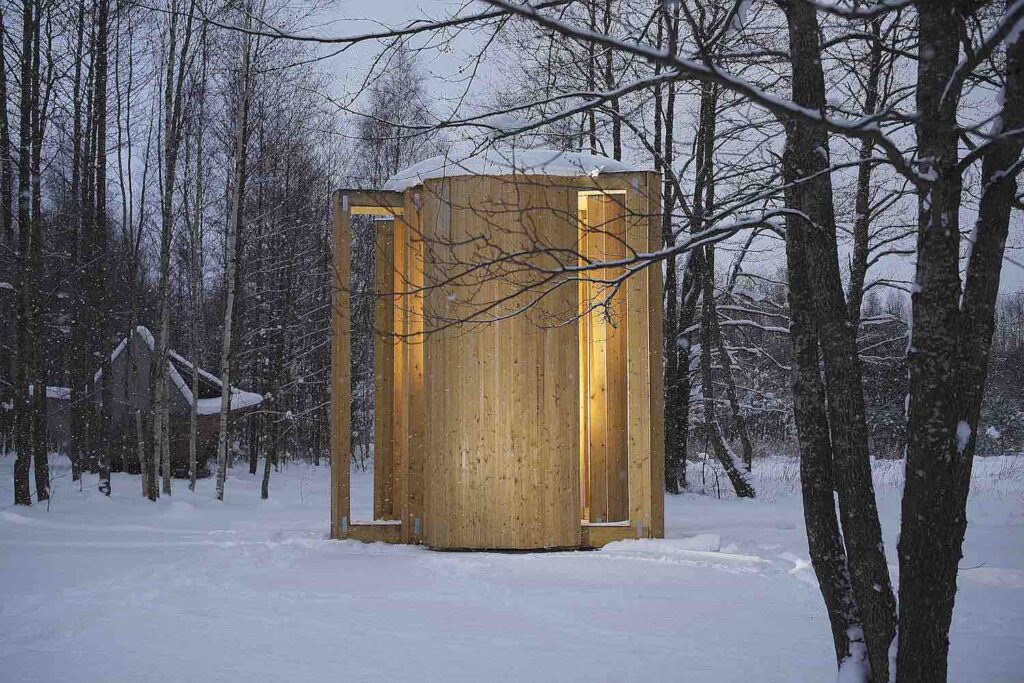

Paco Ulman is an architect and photo artist, who uses photography to describe spatial peculiarities by beginning where the architect left off and where a photographic intervention enables catching the moment to bring forth that which is spatially paramount. His image focusses on unconstrained space and spatial use.

Paul Kuimet does not describe himself as an architectural photographer, but image space, space caught in or set up in an image is largely the focal point of his contextual and conceptual art.

Tõnu Tunnel

I’m not sure I can say what is important in a photo. As Edgar Valter’s pokus say, once they arrive at the right spot, they get an overwhelming feeling and they just know. It’s important to get a feel for the space. Is it a house or a landscape or a human-sized installation? Is it interior or exterior space or a mixture of both? Or a meta-level allusion to some spatial format that doesn’t exist yet? The function of a photograph is to save, archive and convey in two-dimensional media spatial experience for those who are yet to experience it directly.

Practice has taught me that architects always want to capture the entire building. And context. And the flora and fauna characteristic to that specific lot. But they do not want to see wide-angle lens distortions. An ideal photograph should communicate the original idea of the architect and the client’s vision, without the hanging tree branches or power lines or vans parked in front of the house with emergency lights on. Although, I don’t mind a tasteful car in appropriate colour coating. Budget cuts and spontaneous contributions to architecture should be left out of a photo. Instead, I prefer getting close to the touch and feel of the material and the lighting. A photographer should consider perspectives recommended by the architect, but remain free to provide surprising and complementing interpretations and connections.

What a person considers important in an image is ultimately particular to the individual. It depends on the where, who and why. Even the function and essential meaning of an existing photograph may change over time.

When taking photos, it is important to me personally that I avoid blindly following rules that someone else may have written earlier, and that I try to have more trust in my own intuition. I want to take photographs in a way that enables getting the same feeling as on site when looking through the photos later. And photos shouldn’t make you bored, not when you are taking them or later when you are looking at them. It’s great when you manage to take a picture so multi-layered that a seemingly simple scene keeps unravelling in the second, third or fourth time that you look at it. I am yet to get to the core of why it is possible to gaze at a landscape painting for 30 minutes but not a landscape photograph. If I manage to instill the pleasure of this slow watching procedure into a single series of architectural photos, I might be ready to retire. But until then I must keep searching.

A good photographer is able take any building and produce a shot that works as an image surface and also captures the viewer. When standing behind the camera, are you able to recognise the spatial quality of the architecture and discern between good and bad practice? When you look at architecture, do you contemplate on the architectural process or try to understand the reasons why an architect may have applied specific ideas or why this or that has happened?

I am currently mainly involved with the subject of architectonics. I aim to mentally conceive and deconstruct what an object consists of. I am studying terminology and methods how to articulate and decompose volumetric space, hoping to be better equipped to grasp the architect’s thought process. Why these elements, why this location, why that scale or those proportions? Ideally, I am able to sense it or the architect provides the input on what the backbone of a project really is about. It is the sketch on the napkin that was drafted during the first meeting with the client.

Since I am still fairly young and with somewhat limited experience, I am only now experiencing a certain growth in courage to have an opinion about architecture. The more I investigate, the more I learn to see spots with strange joints where the contractor has cut corners, so to speak.

Discerning between good and bad architecture is largely a matter of gut feeling, I suspect. Does the space function as it is supposed to? Do you feel good when spending time there? Am I able to identify my location within the building and am I able to navigate there without having to ask for help? During my photoshoots it is always fascinating (but tedious) when I have to explain myself to all kinds of security personnel who come to ask me what I am doing there. After hearing a satisfactory response, the bored security guard doesn’t want to leave, lights up a cigarette instead and starts talking. This is actually where the practical drawbacks of a young building surface. The pains of tuning climate control, problems with acoustics, illogical switches or details already wearing down – almost all the things that need to be covered with the architect in the preparation phase and paid attention to on site during the shoot. Flaws and failures to muffle a bit in the future, or excellent solutions to highlight.

Paco Ulman

Concept! – says the proper artist. Aesthetics! – says the photographer. Technical execution! – says the other photographer. Space! – says the architect. The cute factor! – says the Japanese architect of small houses. Story! – demands the journal editor. Likes! – sighs the influencer. I know exactly what it is but I’m not telling you! – snaps the art critic. Sometimes I feel I might know! – says the author.

A good architectural photo is a continuation of an architectural piece. Seeing that it is impossible to take a first-hand look at all the buildings in the world, the image becomes somewhat architectural propaganda or on the contrary – its judge. To think of it, most of our architectural memory is a compilation of what we have seen in journals or on websites. The photograph is one of the last links in the construction phase where drawing conclusions and contemplating on whether the job was well done or not becomes possible. An architectural photo is always contemporary, it is like the latest word in architecture, outdone only by the next photo series of the next object. Based on these photos we then interpret space, recreate the narrative of contemporary architecture. The coinciding danger here is that we may become so enchanted by the novelty effect and image quality that we lose ourselves in the picture and forget that it is in fact a space for someone to inhabit.

In my practice I have taken architectural photos mostly on commission, where I follow an established image layout and format since it is a conservative genre that adheres to fairly strict rules. The client and the audience both prefer to communicate in an established language. The photographer’s work on site is like a dialogue with the architect that is happening in his head. It is similar to the relationship between the architect and the client, where the two attempt to formulate complex spatial relations into one whole. Interpreting this volumetric abstraction into a two-dimensional shot is one of the most interesting parts of an architectural photographer’s work. A successful dialogue between the architect and client is usually apparent in the photos as well. In such cases it is not hard to highlight significant spatial nuances, since it is clear that someone has already thought through the scene and all I have to do is pick it up.

You describe spatial photo as the last phase of creating architecture but isn’t that really just the beginning of a building’s life cycle? All the lives and everyday that will be happening in that architecture – could that not be an intriguing testimony to whether the architecture is good or not? How best to navigate between the formal post-project architect-incipient image and the informal user-centric actual world? Sooner or later you will be dealing with baroque kitchen furniture. Should that be cut out from the frame?

That’s precisely what’s interesting! For the architecture audience the building is completed and ready and the time has come to place it on the history shelves and move on, but for the resident or the user, the life span of the building has just begun. It seems architecture has an incessant need to be continually new and exciting, seldom can you see analyses of 10-year-old buildings between journal covers. On the contrary, 10 years is an almost embarrassing age for an object, it is outdated. Concerning home baroque, I personally like giving life to pictures, even if it’s absurd. It enlivens the image and relates to the space better, giving clues about who might be dwelling or working there. It is problematic when design leaves no room for the inhabitant or user – when the author has tried to solve every last detail and push out the rest. It reminds me of the beginning of the 00’s when the interiors were swept over with minimalism. Stores offered lame materials and product range was limited. Everyone wanted to create open and light ambience, but the resulting image was uniform and blank. I believe in the capacity of the image to tell the story of space and I regard it as extremely important in architecture. All the more, I am intrigued by questions that delve deeper than the surface layer.

Ott Kadarik

My long-time experience @kodarik says that any picture is made significant by the following notions:

#abandoned #abandonedafterdark #abandonedbuilding #abandonedmilitaryplace #abandonedplaces #agameoftones #archidesign #archiloversarchilovers #architect #architecture #architecturedose #architecturelovers #architecturephotography #arhitektuur #asia #awesome_earthpix #awesomeglobe

#beach #beautifuldestinations #bonfire #broadcasting #broadmag #brutalism #brutalistarchitecture #building

#capturestreets #china #chinaculture #chinalife #chongqing #city #citybynight #cityexplorer #citykillerz #citylife #coalmine #colorphotography #colors_of_day #communistarchitecture #concrete #construction #contemporaryphoto #contemporaryphotography #countryside #createexplore #createexploretakeover

#d #decay #design #detail #discoverglobe #documentary #documentaryphotographer #documentaryphotography #documentyourdays #droneoftheday #dronephoto #dronephotography #dronepilot #dronepointofview #droneshot #dronestagram #droneview #dscvr_earth

#earth_portraits #earth_shotz #earthexperience #earthfocus #EarthOfficial #ecofriendly #estonia #europe #everydayvietnam #explore #exploresaigon #exploretocreate #explorevietnam

#fantastic_earth #feature #featuremeinstagood #fire #focus #fog #foggy #foggycity #follow #forgotten #friends #fubiz #futureoffices

#georgia #getlost #getlostwithme #globetrotter #gunkanjima #gunkanhigashishinjuku

#haikyo #haikyoist #hanoi #harasadam #heatercentral #heritage #hochiminhcity #hongkong

#idavirumaa #ig_europe #ig_landscape #igersone #igworldglobal #illgrammers #illkillers #ilovechina #ilovejapan #ilovenature #imaginatones #industrial #instadaily #instagood #instagramjapan #instajapan #instamagazine #instatravel #inthecity #istanbul

#japan #japanculture #japanesemetabolism #japanlife #japanlover #japantravel #jokhang #jp

#kadariktüürarhitektid #kenzotange #kihnu #killergrams #killyourcity #kishokurokawa #kodarik

#landscape #landscapehunter #landscapelover #landscapephoto #lasnamäe #lensculture #lhasa #livingenvironment #lostplace #lostplaces #love

#magazine #magnumphotos #manaboutmodernism #metabolist #metabolistmovement #midcenturyarchitecture #midcenturymodern #midcenturymodernarchitecture #militarybase #mining #modernism #modernismweek #modernismweek2020 #modernmovement #moodygrams #myfeatureshoot

#nakagincapsuletower #nakedplanet #natgeoadventure #natgeohub #natgeolandscape #natgeotravelpic #natgeowild #natgeoyourshot #nature #naturephotography #neverstopexploring #newdevelopment #newtallinn #newtopographics #nightlights #nightpark #nightstreet #nightvibes #noicemag

#oftheafternoon #oldbuildings #ourplanetdaily #outdoors

#peopleinsquare #photo #photodocumentary #photography #photojournalist #photomagazine #photooftheday #photoshoot #photostory #picoftheday

#quality

#reportage #roamtheplanet #roofscape #ruins #rural

#saigon #saigonhistory #saigonlandscape #sea #shizuoka #shoot2kill #shotaroundmag #shotaward #shotzdelight #socialistarchitecture #southeastasia #sovietarchitecture #spicollective #stone #street #streetactivityteam #streetdreamsmag #streetexploration #streetmagazine #streetmobs #streetphotography #streetphotos #streetshared #streettogether #stunning_shots #subjectivelyobjective #submarinebase #superhubs #sustainableliving

#taio #tallinn #tallinncity #tallinngram #tallinnonline #tallinnstreetphotography #tallinnstreets #tallinnonline #tbilisi #techno #thediscoverer #theworldshotz #tibet #timberarchitecture #tokyo #tokyotravel #travel #travelblogger #travelgram #traveling #traveller #travelling #travelphoto #travelphotography #turkey #twgrammers

#unknownjapan #urban #urbanandstreet #urbanlandscape #urbanphotography #urbanromantix #urbex #urbexpeople #urbexphotography #urbexworld #utilitarianarchitecture #utopia

#vernacular #vietnam #vietnamese #vietnamhistory #vietnamtravel #visittallinn #visual_heaven #visualambassadors #visualsoflife #vsco #vscocam

#wanderlust #way2ill

#yngkillers

#колхоз

Paul Kuimet

I don’t consider myself an architectural photographer in the classical sense, although I have depicted architecture in my imagery and used its agency in the decisions concerning presentation of my works in exhibition spaces.

It is difficult to answer the question on what matters in a photo, because describing the success or failure of a photograph is possible using the formal aspects of an image – from the standpoint of the selected viewpoint or perspective, composition, tonality and lighting. The single image excludes context which is why it is harder to illuminate an ideology that one or the other building may be representing.

Therefore, it might be better to ask what matters in photos. The indicated plurality would facilitate discussion about image sequences and the underlying context. Every so-called real architectural photographer would probably agree that context matters. Shifting the camera half a metre to the left or right will immediately produce a very different image of any building. This context would remain invisible to the viewer if the photographer supplied only one image.

Since my work as an artist involves image contextualisation in addition to the formal aspects, then in some regard it is easier for me to work with film. The succession of film frames (and the implied contextualisation) is dense – as we well know, one second fits 24 frames. This density also means that context is in perpetual motion and amorphous by nature – despite the contemporary expectation for an artist to produce clarity, translucency and articulation.

These film frames depict the change of one architectural image over time – Infomart in Dallas morphs into its formal predecessor, London’s Crystal Palace which in turn changes into the European Parliament in Brussels. This formal link and similarity together with the frame rate (as noted, 24 frames per second) thus places these images in context and provides the chance and starting point for a discussion on ideologies surrounding these buildings.

As a viewer I sense a documentalist and conceptualist spirit in your imagery that describes occurring spatial processes. At the same time you are able to stage these processes yourself, use photography and context to manipulate and invent spatial processes even when shooting in the real world. How big is your actual contribution as an author and conceptual thinker when you are making sense of the content behind the image and are you trying to convey it as a documentalist? Or, do you reserve the right to a certain producer-writer-artist fantasy based on aesthetic considerations?

I don’t consider myself a documentalist, that is, if by that you mean the kind of documentary that prohibits manipulation with the photo or film material after shooting, or at most is limited to colour and contrast correction, adding sound and montage, which in essence are actually significant manipulations. But that wasn’t your question, was it?

It is easier for me to speak on the basis of specific works. For example the film “Golden Home“ (2017) rests on the assumption of a “documentary“ layout of buildings, referring to Toomas Rein’s “Golden Home“ and its neoliberal counterpart in the backyard of a building. In the post-production phase I have cut something out of the film, added props to a scene and ultimately the camera is „swimming“ through the walls of the building and the film starts again. Therefore, I am treating the material with extreme ease (not to say, plastically). Yet, in as much as the starting point of the film is still that one architectural reality, then naturally I reflect on the history of the depicted architecture, its (ideological) status nowadays, on Soviet and modern politics. This becomes the incentive to make the film, all formal and compositional decisions come later. At the same time, the architecture, the colours, the lighting, etc., all had to bear a certain quality from the very beginning. Otherwise, I may not have noticed the scene in the first place.

The 16 mm film „Material Aspects“ (2017) is an exceptional work in the context of my practice, since it is a direct display of the entire research and reflection process (which have all been left out in earlier works), I could say it forms the core of the film. Perhaps this film is the perfect answer to your question? It is based on actual historical events, but the material has fallen into the chain of artistic exaggerations, comparisons and connections which I have then exploited under poetic licence.

In a formal sense it is my most thoroughly composed film since it was shot in my studio from beginning to end. Therefore, each composition includes very little chance, compared to the “generosity“ of documentary approaches where the frame often retains more than the author initially planned. Composition, tones, changing light and other things are as important in this film as they are in my other works, but I must agree that this film is largely “directed“ by sound or text. For that reason (disappointedly, even) I have refrained from using sound (with one exception from a long time ago). Sound and music are emotional and sentimental manipulators which take something away from the image. In the traditional sense, the point of visual art is to depict an image. For example, Gustave Courbet’s painting “The Wave“ (1870) should elicit an “aural“ experience in the viewer just by looking at the depiction of the sea or waves, and not because an actual sound has been added to the depiction. In a sense I don’t see why an optically transmitted image (be it foto or film) should be any different.

JOHAN TALI is an architect at Molumba, a doctoral candidate and teaching staff at the Estonian Academy of Arts, and co-curator of the Open Lectures-series, organised by the academy’s Faculty of Architecture.

Header: Ott Kadarik “In a Bundle”, Tokyo, 2017.

Published in Maja’s 2020 spring edition Maja 100! (No 100).