In recent years, environmentally sensitive apartment buildings have been constructed in Tartu city centre that timidly yet vigorously test the boundaries of the current way of life.

When you ask residents of Tartu why it is good to live in Tartu, the reasons given may be surprisingly similar whether the answer is given by a spatial planner, developer or a citizen. They always mention the compactness of the city and the unique interconnection of the urban and rural lifestyle right in the heart of the city. However, the poor planning of the boom years has left its mark on the city and Tartu is not unaffected by the pressure of urban sprawl either – whether it includes moving buildings with an important public function to the edge of the city, suburban apartment building developments or the preference of the growing middle class for a house in neighbouring municipalities. Fortunately, the economic crisis allowed the given problems to be left on the desk for a longer period of time and it may perhaps be said that a complete turn in terms of the spatial worldview has taken place in the spatial planning in Tartu.

The focus of the new comprehensive plan adopted in 2017 is on empowering the city centre including, for instance, the densification of the centre with new mixed-function residential and commercial premises and giving further priority to high-quality public space.1 The aim is to establish a bustling pedestrian-friendly centre and a cosier living environment for everyone. However, as the city’s resources for construction are microscopic, the actual physical environments are built by private developers who have the capital and thus also the power to decide what and where is actually established. However, in case of Tartu, it is important to highlight and set as an example for other municipalities the persistence of the city government to demand architecture competitions which is the basis of a successful development and the best means for promoting high-quality spatial design. When adding also the active neighbourhood associations and the preparedness of the local people to demand high-quality urban space, it may be said that the social control over the planning and construction processes in Tartu clearly exceeds the Estonian average and thus also forces the developers make further efforts. However, can development based on private property generate social diversity and spatial balance?

The present article will consider the more recent residential architecture in Tartu with its activity now back on the level of the economic boom years. There is a huge number of approaches to the topic of living in the city from home decoration to social issues. The present article addresses apartment buildings in the context of urban space studying extent to which the environmental sensitivity has contributed to successful architecture while also attempting to figure out who all the new homes in Tartu are built for…

Enriching the old town

The comprehensive plan sees the old town of Tartu primarily as the centre of the university city of international importance but also as the venue of active and alternative cultural life. The few gaps in historic street fronts are planned to be filled with buildings with commercial premises on the ground floor and residential functions on upper floors to keep the old town as an active living environment. A large majority of the new or renovated residential housing in the old town now function as short-term vacation rentals – primarily for the employees of the universities and the related institutions (and wealthier students) but also for the visitors. The new buildings in the old town of Tartu tend to be boldly contemporary for a number of reasons. Firstly, the architecture in the old town is highly varied for historic reasons – the dense urban fabric features various eras side by side providing the national heritage officials with more open-mindedness than in Tallinn. Modern solutions considering the historic environment are also conditioned by the above-mentioned requirement of architecture competitions.

Good examples in this respect include the aparthotel Konrad2 in Küütri Street (OÜ Sport, 2016) and the apartment building with serviced apartments in Lutsu Street (AB Eek & Mutso, 2017) that use different means to blend in with the neighbours in the dense urban fabric. The angular form of Konrad, having received widespread attention yet hidden in the courtyard, stems directly from the location of the plot and the heritage protection requirements, with clever touches added by the external staircases and the garden lifted up on the roof that compensate for the lack of light in the narrow plot. The building would have a truly enriching effect on the urban space if the metal fence to the courtyard and roof terraces was open for citizens. If Konrad with its dark concrete panels is manifestly contemporary, then the building in Lutsu Street with its concrete façade imitating the pink cladding of the neighbouring house and its sloping eave has a somewhat insecure yet flaunty effect, but it is nevertheless an exciting addition to the spatial variety of the old town.

Hopefully also another “gap filler” will soon be completed at the corner of Gildi and Rüütli Streets – the modern extension by architecture office Kauss Arhitektuur to the bold corner house with bulwark balconies by Arnold Matteus. After the renovation, the building from 1930s will have flats on the top floors and a new narrow volume with commercial premises on the ground floor and rental apartments on upper floors, there will be a small courtyard between the two volumes with the façade of the new building covered with perforated metal layer drawing patterns of light and shade. The old town would be given an added value and an unexpected vertical dimension by the roof terrace suggested by the architects that is connected with the commercial premises on the ground floor.

Singularity rooted in the context

Large city centre apartments are an alternative for wealthy middle-class families with a fast-paced life and appreciation of comfort, who are tired of commuting and mowing the lawn and only wish to enjoy the comforts offered by the heart of the town. As the purchase decision in such cases is more based on emotion than on needs and also the buyers are more informed and demanding, the developers are forced to make an extra effort for the sake of quality and added value. A good location and larger number rooms are no longer enough, you also need high ceilings, spacious balconies, storage, high-quality materials and something extra – something that makes it an identifiably unique home in a balanced dialogue with the environment. One of such high-end luxury apartment buildings in Tartu that diligently strives for meeting the above-mentioned baiting criteria is located in Kitsas Street at the edge of the old town (Salto AB, 2017). The building stands out for the grand staircase bathed in light that separates the large volume into two and also for its location in the pedestrian street with a prominent relief that is further animated by the doors and gates placed on the various levels of the steps forming the enclosure wall. It is also a highly photogenic building, however, on closer inspection on site, the profusion of details comes across somewhat overblown and awkward.

On the other side of the old town, similar living standards but in a more minimalist key better aligned with the context are provided by a small outbuilding with three flats on Kloostri Street (OÜ Sport, 2017) that was developed by the residents of the house. The building attached to the firewall of the neighbouring house on a narrow plot seems like a small relative of Konrad – also here, the highly simple architectural form directly derives from the shape and location of the plot with further characteristics added by the diagonal of the glass stairway crossing the side façade. The flats extend throughout the building and allow the residents to choose whether they prefer to adopt the rhythm of the old town overlooking the tower of St John Church or the more peaceful wavelength of Supilinna district. The requirements for new developments in the adjacent Supilinna district are highly strict, thus the dark concrete building with wide glass surfaces in Kloostri Street illustrates well that the quality of cultural and environmental value does not necessarily come from the selection of materials.

Tähepargi development

Within the past twenty years, the wooden building areas in the town centre, primarily Karlova and Supilinn have evolved from dodgy ghettos into some of the most desired residential districts in Tartu. Active people seeking for an alternative lifestyle began reconstructing old buildings thus bringing new life to the area, they were soon followed by the developers seeing the profit potential in the increased cultural and environmental value – precisely as it always happens in urban regeneration with the development of welfare society. Today, the gentrification of the wooden building areas in Tartu has reached a stage where the prices are still increasing and the people who revived the neighbourhoods have a hard time protecting the areas of cultural value from the pressure of developers and from turning them into posh city districts. The given battle is well illustrated by the lengthy dispute over Tähepargi development that is about to reach its eventual urban form after fierce clashes, including in court, between the developer, city and neighbourhood associations. Pursuant to the earlier comprehensive plan while running over the thematic plan of Karlova, the developer managed to place 12 new apartment buildings into the urban park and sledging hill loved by the locals and push the public area to its minimum at the corner of Tähe and Pargi Streets. The only victory on behalf of the city is the construction of Öö Street across the quarter connecting the new buildings better with the urban space. There was a vision competition for the architectural solutions of the quarter, however, due to the meticulous requirements stipulated in the detailed plan, the architects could only provide the constructions with an appearance that would consider the cultural value of the area. The attractive buildings with well-considered layout designed by Anu Tammemäe are undoubtedly comfortable places to live and enjoy nature and birdsong from the balcony, however, it is doubtful whether the monofunctional and semi-private environment replacing the beloved urban park will add something to the general urban space and, as we know, only time will tell. It would also be interesting to know how well such “urban oases” sell – according to statistics, the sales numbers have reached the peak and new apartments sell at the rate of 50 per month, while precisely four homes costing more than 200,000 euros were sold in 2018. Considering that Tähepargi quarter includes more than 20 apartments in the given price range, it begs the question of who they are built for.

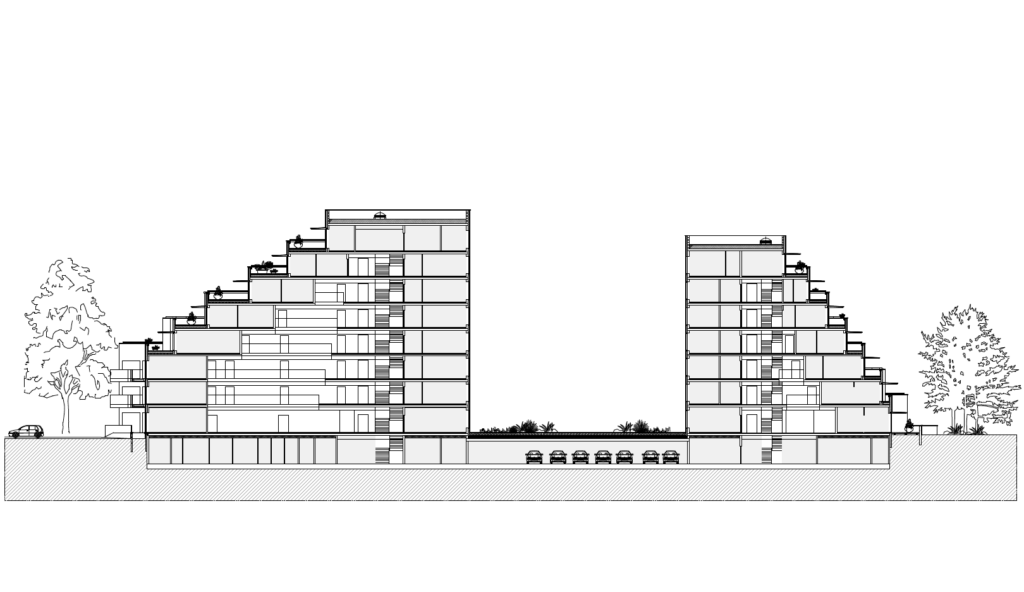

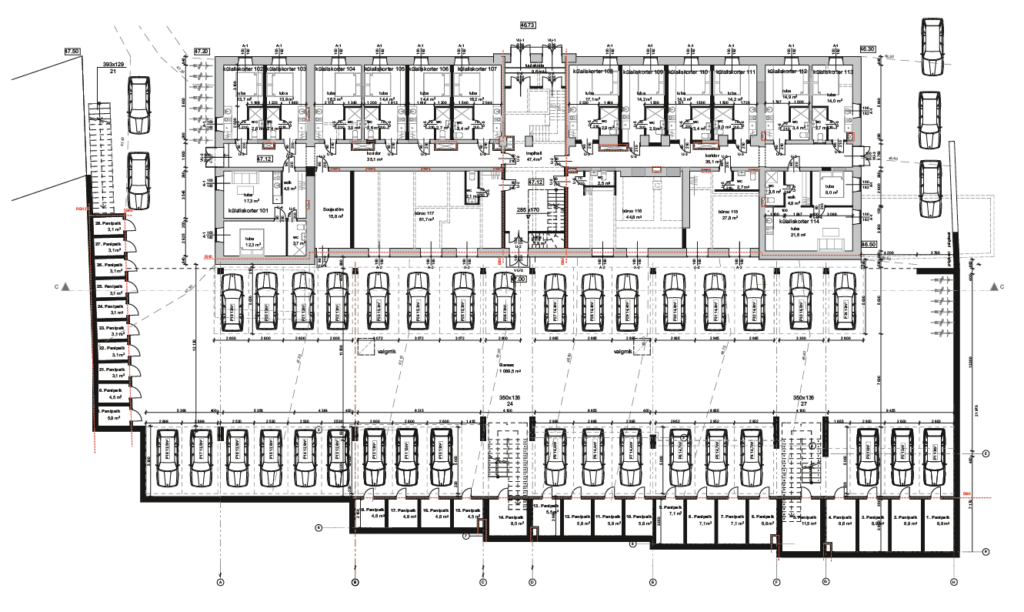

Terrace buildings in Riia Quarter

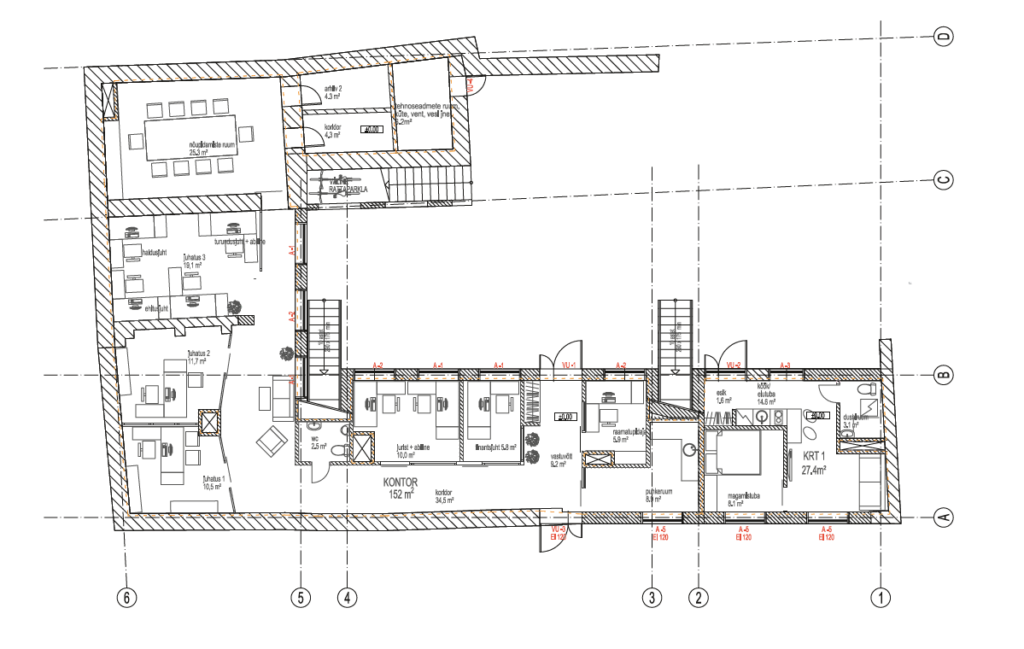

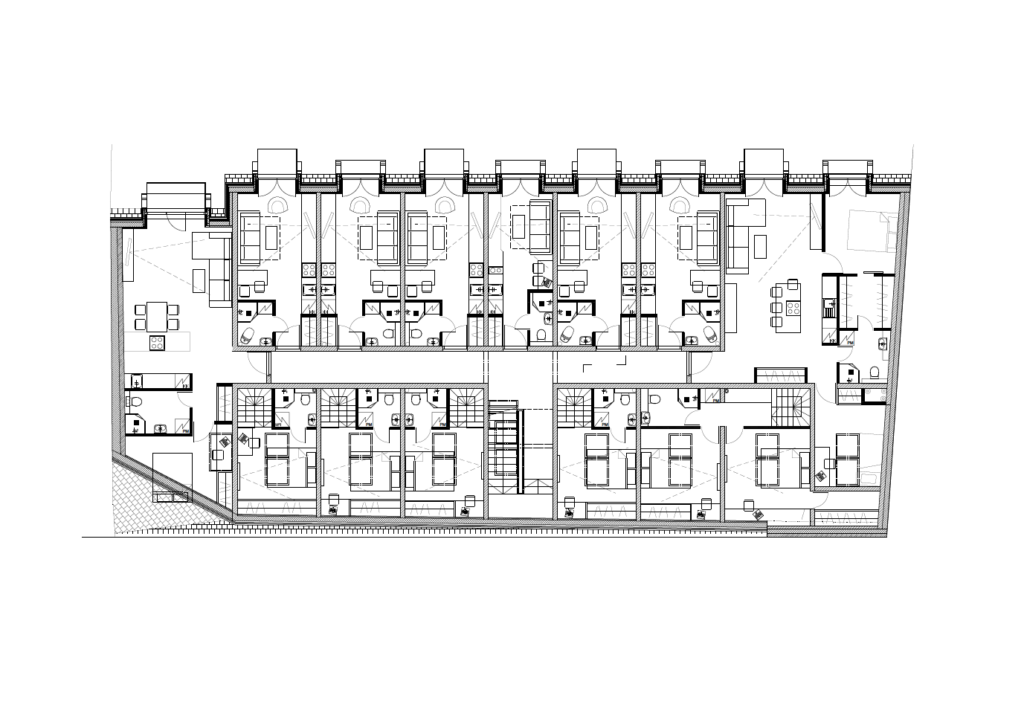

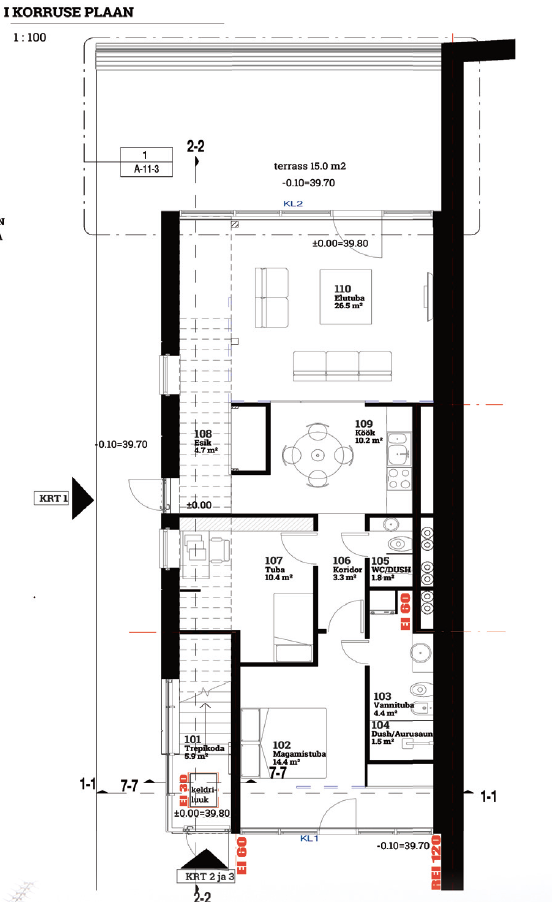

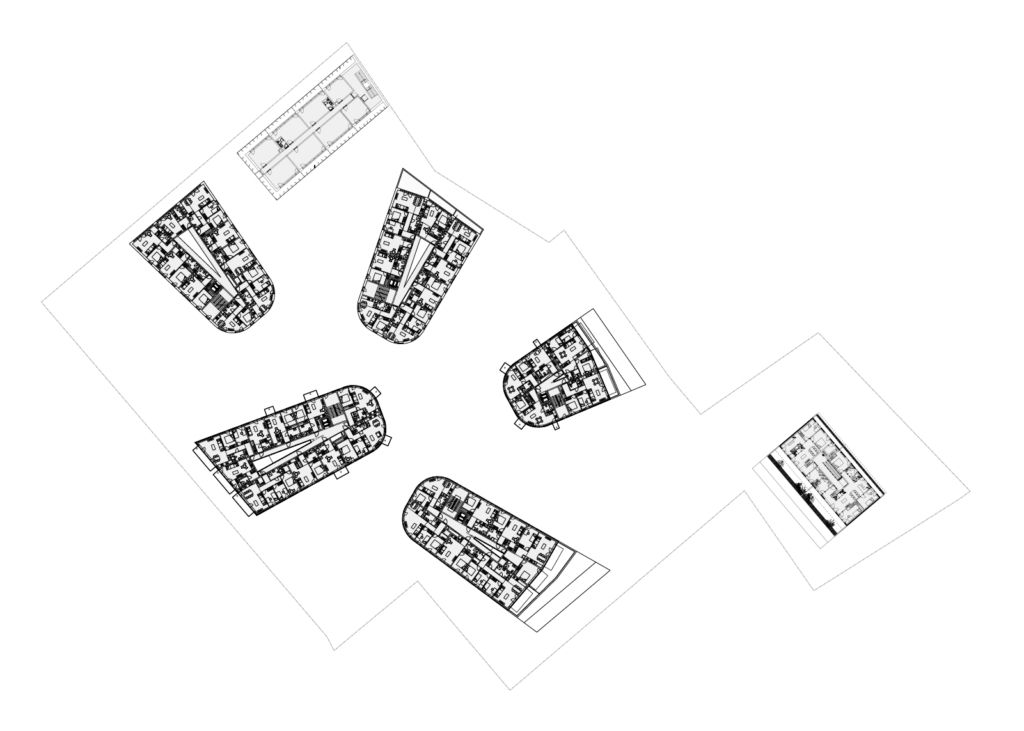

Another apartment building complex with its planning rooted in the boom years is emerging in Tartu city centre under the name of Riia Quarter envisioning seven 3-8-storey buildings on the former taxi parking lot with more than 200 flats and some commercial premises. Two buildings (with respectively three and eight storeys) are completed and almost sold out, with the next one completed in autumn 2019. Salto won the competition already in 2006, however, this project has greatly benefitted from the standstill brought about by the economic crisis – the area is now ripe for such a large-scale urban design addition (greatly enhanced by the activities in Aparaaditehas) and also the architecture has taken a clearer and more precise form. The main idea of the quarter lies in the dome-like effect created by the buildings with dual essence (combining high-rise and terraces) functioning as a kind of a switch between the dense and metropolitan Tartu and the greener garden city environment. The density of the quarter is compensated by the underground parking freeing the space between the buildings for green areas for pedestrians, with an additional touch given by the sledging hills formed by the entrances. The flowing form of the architecture ensures good views from the flats facing the courtyard while the wooden and red brick surfaces of the façade provide further cosiness, but the strongest trump card includes the large balconies and the best views in Tartu. As in terms of floor plans, the buildings offer flats of various size and shape, the developers claim that the buyers are great in number and varied in profile, perhaps another sign of a good living environment is that almost all flats have been bought for buyers themselves (or children, parents), not for rental.

Three Brothers in Ülejõe

If the buzz around Aparaaditehas has somewhat unexpectedly turned the former traffic artery Riia Street into one of the key areas for the gentrification of Tartu thus extending also the development of the city centre towards Riia Hill, then on the other side of the Town Hall Square, the fight for the attention of citizens and developers has been undertaken by Ülejõe city district and its area closer to Annelinn in particular. The city held a planning competition for Fortuuna quarter already in 2004 with its urban design ideas based on a city centre that appreciates the variety and interaction between functions, social groups and urban space. The winning solution by architecture office Urban Mark that was later adopted as the detailed plan brings the buildings together as a united front on the street perimeter with private spaces within the quarter and a public green area connecting the entire area. The first development that has managed to reveal the full urban design potential of the planning is the complex Kolm Venda combining residential and commercial premises in Pikk Street. The invited architecture competition by Avaare Kinnisvara was won by the entry of Kauss Arhitektuur that articulated the massive building in the detailed plan into smaller volumes befitting Tartu while also providing the flats with more light and freeing the courtyard from the entrance to the underground garage which allowed a cosy and varied semi-private space be established between the buildings. The landscape solution and greenery consider the damp riverside climate and the potential flood hazard, for instance, there are concavities for water features left in the raised ground. The extra effort by an experienced developer for better results is clearly evident in every step – starting from the imposing balconies with complex glue-laminated timber construction up to the staircases with unique doors and plywood paintings by the architects. In terms of layout, it is worth noting the studios with high ceilings (4.5m) and a mezzanine. If the spirit of Kolm Venda is continued, Fortuuna quarter could become an excellent riverside residential environment shifting Ülejõe psychogeographically closer to the centre, especially as the previously peripheral area is actually only a 10-minute walk from the Town Hall Square. In the interest of the cohesiveness of urban space, the public space within the quarter could have been left for the city to develop, as now we can only hope for the good will of the developers.

New urban regions

Be the vision documents as they may, the majority of apartment building developments are and will be located outside the city centre with fewer regulations and more space making the prices considerably lower. A new urban region is a business project with a high profit margin and the given attitude is often reflected in repetitive commercial architecture and environments disregarding the local spatial heritage. The parking norms do not contribute to it either – around 1.4 spaces per flat requires some effort from the developer and cleverness from the architect to generate any traffic-free common areas around the buildings. There are new such districts emerging, for instance, in Kvissental, Ränilinn, Tammelinn and Ihaste. The architectural quality is varied, however, it is worth noting that in case of several developments, both developers and architects have come to set Tulbi-Veeriku district as a good example (AB Pluss, 2006) where the space between the buildings was designed as a raised green garden landscape, and most importantly with no cars. Tulbi-Veeriku quarter was one of the first areas with a comprehensive environmental planning established after Estonia regained its independence and it is important to remember that in addition to the location and good planning, today’s buyers also appreciate increasingly more the high-quality spaces between the buildings.

Micro-flats

Despite the profusion of new residential premises and somewhat wider selection of locations, the flats in the market still tend to be somewhat standardised and do not really consider the changing needs of the society. They still strictly follow the norm of keeping most of the flats with two rooms, a smaller proportion with three rooms with a couple of studios and four-room flats added in. Their proportional division and the layouts recur unchangingly from development to development. Are people’s lifestyle choices really so limited as the real estate agents say?

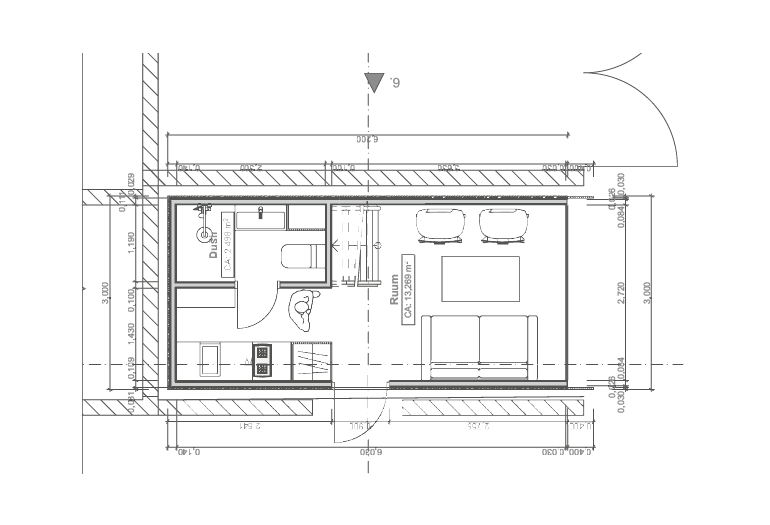

Nevertheless, there is one new trend in the housing market in Tartu – micro-flats (up to 20 m2) providing the bare minimum in a compact form spring up like mushrooms. The high property prices, changes in working and daily life as well as the increasing mobility have created a great demand for such small flats and the developers naturally strike while the iron is hot. Micro-flats are a good way to give new life to abandoned buildings – an example here is set by the former office building in Kastani Street (Sõbra Kinnisvara) that was renovated as cost-effective rental flats for students. After years of abandonment, also the ground floor of the renovated Pargi Sauna has been taken into such use. The residential housing requirements for micro-flats are more flexible allowing them to be developed also on commercial land and thus providing the developers with the means to squeeze every drop out of the sold premises. In terms of typology, small flats would be a welcomed opportunity for young people taking their first steps in their independent life and also a good landing place for the elderly, however, the current trend is primarily aimed at investors and thus merely tends to increase the average price per square metre (the price of micro-flats in Tartu is largely above 3000€/m2).

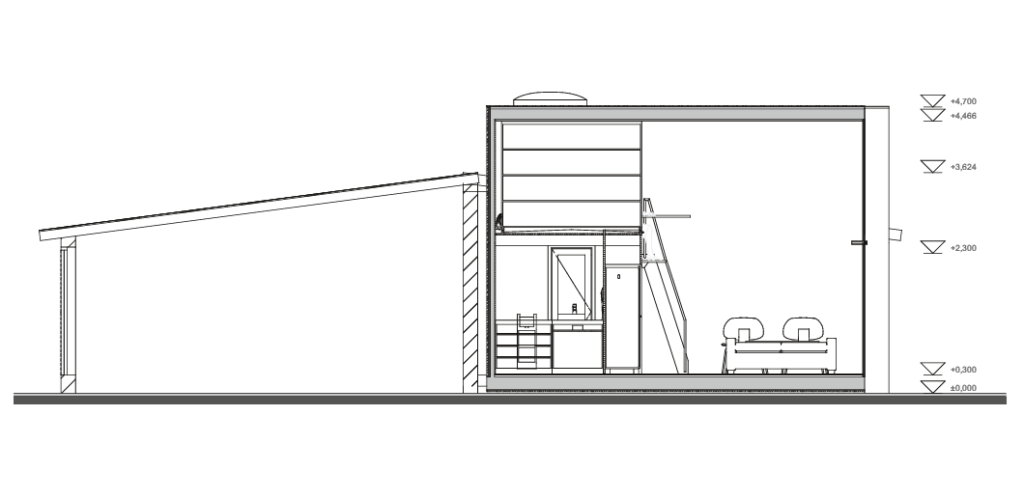

3D graffiti

As an alternative to the highly expensive short-term rental apartments, the former city architect Tiit Sild has offered a micro-building representing a completely different school of thought. One of the cells in the abandoned garage district in Lubja Street has been replaced with a manufactured module building that does not require a construction permit due to its small size but does include all the necessary means for leading a decent life. The architect of the house is dreaming of an entire quarter of such micro buildings – a kind of a micro-district that would carry the message of saving energy and space and the possibilities of interim use. The idea is by no means new in Estonia, however, differently from the exclusive luxury items such as KODA and ÖÖ, the residential box in Lubja Street carries the feel of austerity befitting Tartu and, what’s more, it is affordable. The luxury is here expressed in freedom – from excessive materiality and design and even from a permanent location, as the unit can be easily relocated by a crane when necessary.

Perhaps we need a new economic crisis to jump off the bandwagon of exclusivity hyped by the real estate market and find ourselves in a situation where clever and affordable strategic solutions must be found on the state and municipal level to provide choices that meet the needs of various social groups.

PILLE EPNER graduated from the Estonian Academy of Arts specialising in art history, she now works for the same school as the Research and Development Coordinator of the Faculty of Architecture, sometimes writing about architecture and curating exhibitions.

KALEV KASE is a board member of the real estate company Avaare Kinnisvara OÜ in Tartu. The projects developed with his contribution include Kolm Venda (2017) and Tulbi-Veeriku quarter (2006) that focus also on the spaces between the buildings.

Pille Epner: What are the latest trends in residential developments from the developer’s point of view?

Kalev Kase: The variety in residential construction has somewhat increased. There are both more expensive city centre apartments as well as more affordable and simpler suburban flats that sell the best. In addition, recently there have been several reconstructions of apartment buildings in areas of cultural and environmental value which is a highly welcomed trend. Also the developments of large-scale residential complexes are back so that an entire district or area is built up. We are developing a residential area between Ihaste and Lammi Roads next to nature reserves pursuant to Europan-9 architecture competition. I believe that despite fluctuations, the demand for new residential premises will not disappear and the volume of the present building construction will not decrease in the long run.

PE: In what direction should the residential market and construction move in Tartu so that residents, the city as well as developers would be happy?

KK: In the residential market development, it is important to provide various opportunities for people with various needs. It should be possible to construct affordable flats for young families within the borders of Tartu without overburdening them with mortgage. It would be nice to have areas not too far from the city centre where more affordable apartment buildings could be constructed. It is not easy, however. I don’t think that a financial support system for developers should be established. The city government could have a more flexible or even experimental approach to the development of some areas – with no requirement for parking norms, gross buildable area and some other regulations, reusing projects with some variation. This obviously requires a more extensive plot of land and well-considered management. The supply of flats should be sufficiently high to keep the prices low. For instance, Raadi district meets all the given requirements. We should make sure that the affordable price gives Tartu a competitive advantage over Tallinn. As the construction costs in Tallinn and Tartu are already on the same level, we must find clever solutions. Tartu city government can direct the residential market by initiating more thorough detailed plans, for instance, in Raadi districts, but then the aim should not be the maximum profit from the sale of the land.

PE: What is your experience in cooperation with the city?

KK: The cooperation with Tartu city government is generally supportive. We like to talk about the green living environment focussed on people, the development of cycling paths and public transportation, however, at the same time, the officials still hold on to the recommended standards that abruptly increased the mandatory parking spaces from one to 1.4 per flat. It would be more reasonable to take a more creative approach to all the requirements and not be afraid to make decisions on the basis of the interests of the city as a whole.

HEADER: Aparthotel Konrad, Küütri 8. OÜ Sport, 2016 (developer OÜ Fausto Capital). Photo by Silver Gutmann.

PUBLISHED: Maja 96 (spring 2019), with main topic Spatial Diversity

1 The aim was actually achieved already with the adoption of the widely discussed city centre planning in 2016 that is integrated in the general comprehensive plan.

2 A longer article on aparthotel Konrad was published in Maja 1-2/2016.