What kind of relationship between a space and its surroundings would help to avoid the objectification of space—i.e., treating buildings or areas as sculptures or fully controllable objects?

Objectification or becoming-spatial?

Thinking about space from the perspective of contextuality, we soon run into a slew of paradoxes. This is because the context of something is what surrounds it; yet, space itself is also what surrounds. Attempts to contextualise some space—to surround the surroundings—might be well-intentioned, but it can easily happen that this turns the surroundings into an object.

This probably calls for clarification. For a while now, I have been fascinated by the idea that our engagements with things in the world can take place in two different modes of perceiving, thinking and doing. The first and more familiar mode could be called the objectual mode. In this mode, we make a focused effort to separate some phenomenon or being from a broader field of phenomena and either imaginatively or actually turn it round to inspect its different facets, just like an architect examining the model of a building in a computer programme. The same mindset can be used to study very large areas by mapping them out on a reduced scale to get an overview, or non-physical phenomena by considering them on the backdrop of a broader notional map (like when discussing the significance of some recent novel in the context of 21st-century world literature).

Yet, there is also another mode that is just as familiar to us in our everyday lives, but much less discussed in, say, philosophy. This could be called the spatial mode. In this mode, we are not attending to some object on a background, but the background itself, which manifests in its complete form as surroundings. Background in a more narrow sense is something that could still be captured in a single glance, but surroundings can not—some of its parts will inevitably be left behind the viewer. When we talk about experiencing a milieu, we are already in the mindset of having e n t e r e d somewhere and letting ourselves be surrounded.

In this process, experience has transformed its nature. Instead of focused seeing what has become more important is the peripheral, so-called corner-of-the-eye vision, which is more blurry and linked to the perception of movement. But the sense of sight might no longer even be primary here. Much more importance is gained by other senses that function more holistically, such as hearing and smell, but also various subspecies of the bodily sense, like the sense of balance and proprioception.

In our daily lives, we switch from one experiential mode to the other quite seamlessly and combine them skilfully in all sorts of ways. For some reason, however, Western thought has steadfastly emphasised the objectual mode of experience. This gives the impression that space is likewise something to be experienced in an objectifying way—from the perspective of an active master. In the case of architecture, there has been much discussion of the fact that spatial presentation and design are increasingly dominated by the kind of visuality that objectifies space. To be sure, this can sometimes be inevitable. Spatial practitioners often have no way around it, using renderings, models and drawings to better imagine the space that is being created. But something strange happens with the space in the course of objectification. Namely, if this objectification is fully successful, we have erased the spatiality from the space.

Thus, it seems that in order to become a truly excellent spatial designer, the objectifying disposition needs to be complemented or replaced by another disposition, which could be called becoming-spatial. Paradoxically, in this case we could no longer speak of activity in the ordinary sense. To experience space as space, it is necessary to let it affect u s . This means that we can no longer be the active party. While in the case of objectifying experience, it is we who concentrate something before our eyes, in the case of becoming-spatial this works the other way around—it is space that concentrates us, and no longer as experiencers, but rather as someones whose selves are lost in the diverging, irreducibly pluralistic effects of space.

Just as objectifying experience also encompasses non-physical phenomena, so does the experience and the corresponding knowledge of becoming-spatial go beyond the physical aspect. For example, one can also lose oneself in the story space of a novel or a play. In one way or another, we are immersed in something that exceeds us and cannot be understood by any other means than entering it and submitting to its logic. Yet, this does not necessarily entail a passive state—for example, we can very well be actively creative through being carried by inspiration.

With these observations in mind, let us return to the paradoxes mentioned in the beginning. How to think about space qua surroundings (i.e., to contextualise it) and design it in a way that its surroundings-related aspects would be amplified rather than lost? What kind of relationship between a space and its surroundings would help to avoid an easy relapse into the objectification of space—i.e., into treating buildings or areas as sculptures or fully controllable objects?

Everything begins with the way the spatial practice and its history are taught. If this is done primarily with photos or renderings of exteriors, elevations and plans, then the objectifying perspective dominates. This is consonant with the notion of buildings and their facades as bearers and determiners of social status. For conveying the specifically spatial experience, many architectural pedagogues have emphasised the importance of the section (especially perspective section), which at its best can convey milieu and feeling, spatial events and imagery by involving the human body.1 Still, this observation obscures the relationship the space qua surroundings has with its broader surroundings. Inappropriate use of the section can even boost the perception of the place as an isolated object that has nothing to do with its broader surroundings.

The other pole of the paradox bundle just described becomes apparent from the angle of the p r o t e c t i o n of space (and more broadly environment). Protection is inherently somewhat objectifying, because it implies delimitation, which is one of the basic operations of objectification. To make matters worse, spatial protection is mediated by the concept of value. After all, it is only logical that we should protect spaces that are valuable. However, since value judgements need to be objective, they have to be based on values e x p r e s s e d i n w o r d s . Yet, everyday words, not to mention numerical indicators, have once again an objectifying effect. Spaces or milieus actively resist such attempts at verbal expression. Everyone who has ever found themselves at a loss for words when trying to describe a certain milieu has experienced this. The only kind of verbal expression that has any chance here at all is the poetical kind that conveys its sense through ambivalence, which might capture the ambiguity inherent in space. But poetic words are of no use in the courtroom. Thus, we have no choice but to protect spaces by objectifying them—by stating, for instance, that ‘the interior contains valuable details’.

Surroundings as sources of ideas

Looking at the traditional accounts of contextualism, we can notice a tendency to turn even contexts into a sort of objects. In architecture, context usually means the immediate physical surroundings of a plot, plus (with some luck) the natural, climatic, customary and cultural conditions. Context is turned into a sort of extended plot, which can be used to make adamant demands to match a new building or a detailed plan with what is already there. Understood in this way, we are talking about the protection of a milieu—i.e., the distinct features of a locality. This might seem like a laudable objective, given that contextualist approaches emerged in the 1950s as a reaction to the spread of high modernist sculptural buildings that disregarded the local conditions, and to the broader ideology that posed an opposition between tradition and novelty, inspiring people to take pride in tearing up the fabric of the past.

And yet, this view is accompanied by problems of its own. As I already mentioned, the protective stance has an inherent tendency for objectification. Surroundings as such are volatile and with fluid boundaries, whereas protection can be primarily aimed at some fixed and unequivocal identity of a well-defined area, whether it be Estonia, historical Võromaa, the town of Paide, Karlova district in Tartu or Tallinn City Hall. This brings about a tendency to view such a delimited area as a museum item that is conclusively completed, thus significantly restricting any potential further developments. Hence, critics in the 1980s were able to accuse contextualism of promoting homogenous building fabric and stifling originality, because contexts, presented as something eternal, allegedly imposed fixed solutions and formal choices on creators. This allowed the sculpturalists to present themselves as defenders of architectural avant-garde and autonomy, paving the way for the cult of starchitects that followed.2

With no intention of underestimating the past-directed dimension of surroundings, we can still wonder how to handle that dimension in a way that would not sever its connection with its futurity. After all, there is also a future-directed aspect to values—namely the positive potential of a building or an area. This aspect certainly has connections to the past and its heritage, but also some autonomy. In essence, we are asking—what would be a fruitful relationship between temporal surroundings?

I myself have sought answers to these questions from a vision that I have called, following Toomas Tammis, radical contextualism. It proceeds from the idea that previous contextualist accounts are in one way or another too narrow. First, they tend to emphasise a certain aspect of surroundings over others—for instance, physical environment at the expense of political or psychological surroundings. Second, they focus on i m m e d i a t e contexts at the expense of broader ones. Third, they highlight past-directed aspects of surroundings at the expense of future-directed ones.

Instead, radical contextualism treats surroundings as multi-layered and multi-faceted, inevitably requiring looking at from many different perspectives, using different temporal and spatial scales. Surroundings as such are unitary, but in order to emphasise their multi-layered nature, I have preferred to distinguish climatic, geographical, biological, physiological, psychological, sociological, economic, political, cultural and mythopoetical contexts, and sometimes also the i n t e r n a l contexts of spatial practice, such as structural, material, formal, logistical, aesthetic and personal.

Of course there is no way to objectively break up surroundings into these aspects. Nevertheless, speaking in this way can be beneficial, if the goal is not to give a truthful description of the surroundings, but to treat them as a source for new ideas. Speaking of different types of surroundings helps to pay attention to them in all their richness, looking for fruitful ideas outside the aspects and layers one has habitually looked at.

What gives us reason to speak of surroundings as a source of ideas? Surroundings do not have any powers of imagination themselves, of course, but they can e v o k e ours. The idiosyncracies of surroundings hold different kinds of potentials—troubles and delights, dangers and opportunities that could be either alleviated or amplified. This, in turn, gives rise to corresponding spatial ideas. The desert climate with its blazing days and cold nights demands thick walls made of heat-accumulating materials that would soften the effects of the fluctuating extremes. The climate context of a jungle, where the temperature does not change as much and the humidity level is high, demands thin structures and solutions that would enhance natural ventilation.

In this respect, people sometimes even talk about the determinism of surroundings, as if different surroundings i m p o s e d certain ideas on us. However, the advancement of technology has made it clear that a single problem can have several valid solutions—problems that used to be solved with spatial and structural means are now often tackled with technology (which most often simply pushes these problems up to the planetary scale, unfortunately). In addition, different demands made by different aspects of surroundings often contradict each other, and the spatial designer needs to play the role of a negotiator in order to strike a good balance between competing priorities, all the while not forgetting to amplify the delights.

The situation gets even more complicated and also more interesting due to the fact that surroundings are constantly changing. Climate can warm up. Populations can grow or shrink, and become more introverted or extroverted. There can be geopolitical upheavals, transformations of the legal environment and business climate, not to mention the constant upheavals in culture. This creates new (good and bad) potentials, necessitating alterations in spatial ideas. Of course, architecture as a slow art cannot go along with all the changes. Still, some patterns of change are more enduring than others, and even the short-term patterns should be taken into account in some way. Thus, while surroundings themselves do not imagine, they do prompt imaginations and spatial ideas that would have never come into existence without that push.

Interestingly, this way of thinking about different aspects of surroundings renders them similar to materials. Materials, too, can be objectified—conceived of as resources that can be used infinitely and on which to impose our ingenious ideas. On the other hand, the truly skilled craftspeople have always submitted themselves to their materials, adopting the disposition of becoming-spatial. After all, matter also has the ability to self-form and hence has its own desires and agency. For example, spontaneous forms often arise in the movement of water. The form of tree canopies has emerged as a response to wind, the self-movement of air caused by differences in air pressure. The whole evolution of life is essentially an ongoing and accumulative dance of self-formations of matter, which both reacts to and generates the potentials in the surroundings. It is this self-formation of matter that philosophers Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze had in mind when they wrote about following the materials, like in the example of a master carpenter’s relation to wood: ‘At any rate, it is a question of surrendering to the wood, then following where it leads […], instead of imposing a form upon a matter.’3

Unlike some more flexible materials that let almost anything be done to them and do not really lead their followers anywhere, wood and other difficult materials have the advantage of offering resistance and forcing anyone engaging with them to become inventive, thus increasing the likelihood of delightful unintended consequences. Similar observations also apply to surroundings, whose idiosyncratic desires and agency do not let just anything be forced upon them. It is for the spatial designer to decide what kind of stance they will adopt toward their surroundings-materials at a given moment—whether to impose or to follow. The most productive stance often lies somewhere between the two extremes, because it is namely in the intermediate space where an interactive dialogue between surroundings and creators becomes possible.

Also, this is where a dialogue between different aspects of surroundings becomes possible. This leads to the paradoxical view of spatial design as the design of the structure of junctures or details that surrounds us, where the assemblage of physical materials needs to be complemented by creating working arrangements between the ‘materials’ of surroundings. For instance, such a structure of junctures might bring together materials like concrete, a crisis economy, a largely introverted psyche of the descendants of serfs, an ageing population and a modernist admiration of light and disdain for ornament, giving rise to either bygone and worn-out or new and unexpected spatial forms, which would definitely change quite a bit if some of these materials were to be replaced.

The foregoing also suggests that the idea of a dispute between ‘tradition-loving’ contextualists and ‘originality-loving’ formalists rests on a false opposition that results from an overly narrow conception of surroundings. Even if a formalist decides to go against the immediate physical surroundings, her ideas are still based on a certain cultural, political and aesthetic-formal context. Even if a proponent of the phenomenological approach justifies her judgements of taste with past-directed aspects of the immediate context, it does not mean that surroundings could not also hold surprises, new ideas and values.

The latter observation is especially apt on the collective level. Of course, the distinctness of local architecture can be achieved through individual work, everyone tucked away in their own corner, but it is still worthwhile to also think about collective pursuits. Focusing on a few individual aspects (whether it be wooden architecture, modularity or something else) makes it easier to reach universal solutions, but will not help us stand out, because such solutions usually follow a certain global aesthetic and tend to get lost in a swarm of similar formal patterns. The distinctness and individuality can rather be found by systematically exploring the potentials in many different aspects of local surroundings and bringing them together in different junctural patterns.

Of course, we should not ignore the distinctness that has already taken shape. As the developers of large districts have (often in hindsight) discovered to their dismay, it is very easy to kill off the former fabric of surroundings, but much harder to generate it artificially. Distinctness is like an animal—unlike things that can be produced or put together, it should rather be nurtured. The good news is that, given the range of yet unexplored aspects of our surroundings, this animal should have an abundant food supply for at least a couple of centuries.

EIK HERMANN is a lecturer in philosophy and practice-based theory at the Estonian Academy of Arts, and the editor-in-chief of architecture magazine Ehituskunst.

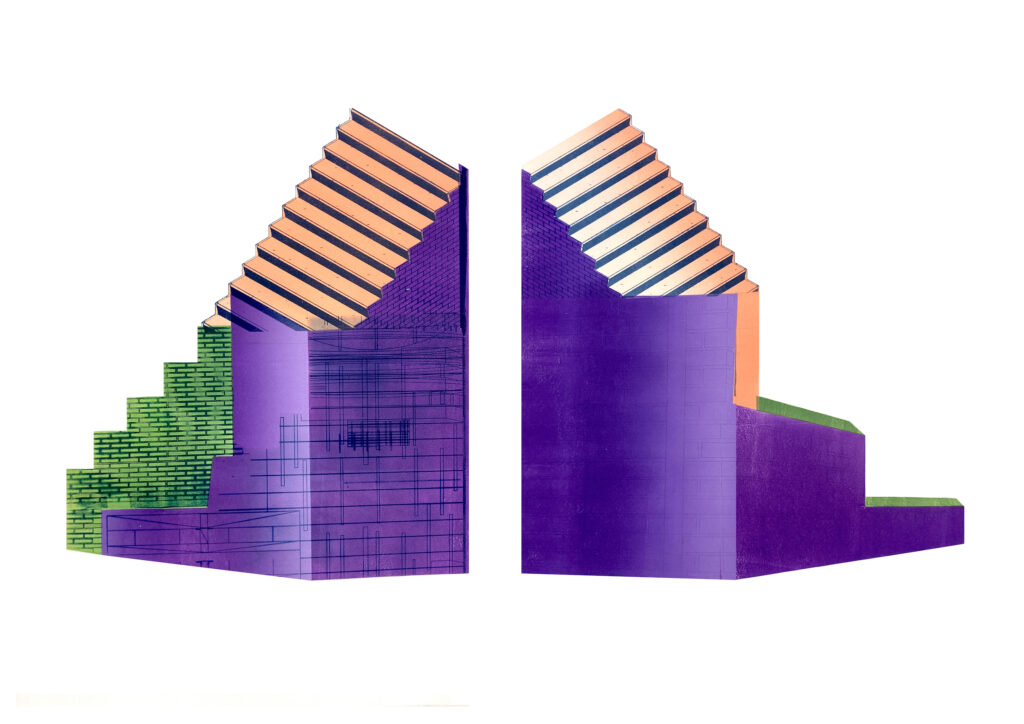

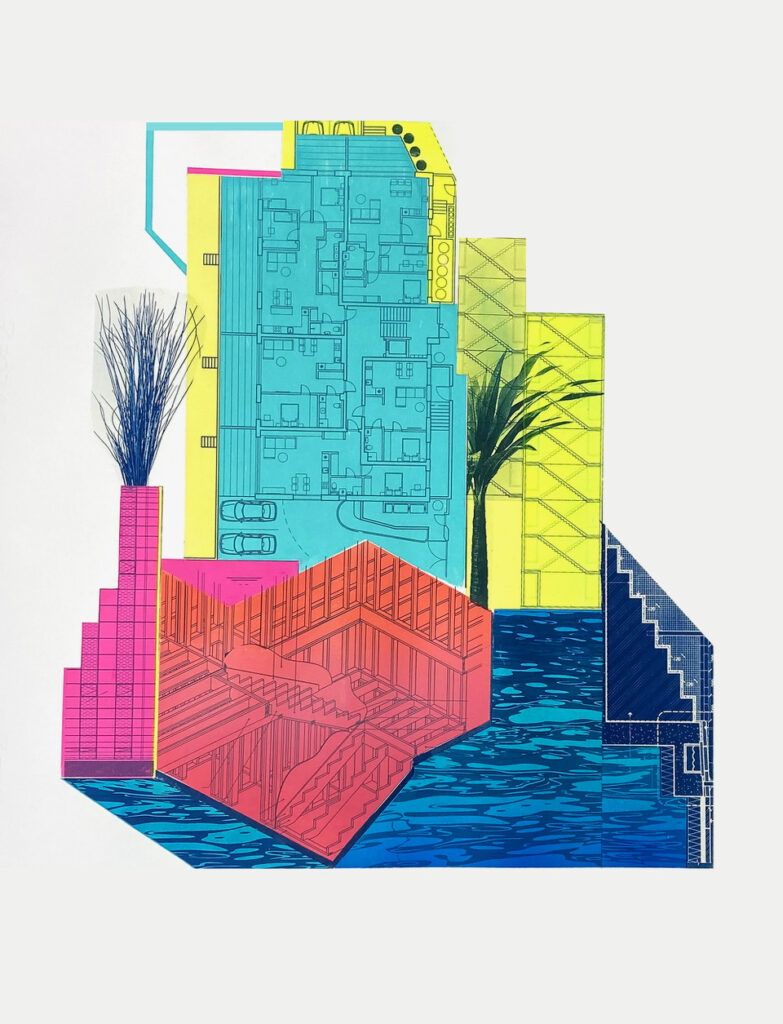

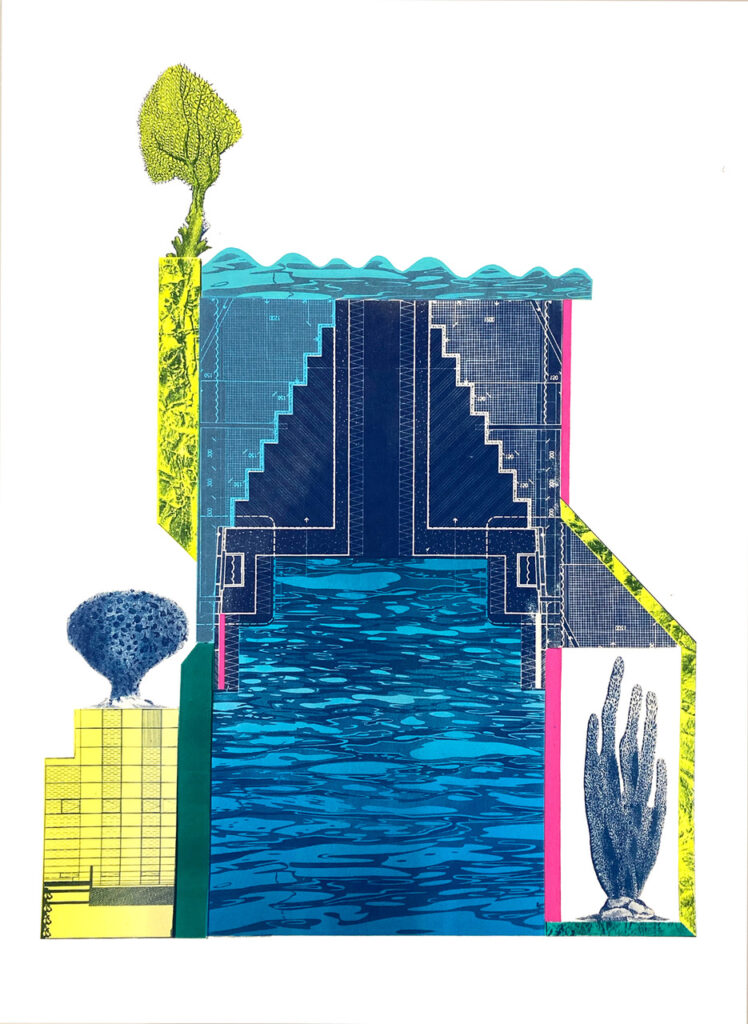

HEADER: Kadri Toom. Packaged City, 2020, cyanotype, relief printing.

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 See, e.g., Klaske Havik, ’Writing Place—Narrative Methods for Topo-analysis’, presentation at the conference Understanding and Designing Place in Tampere University of Technology, April 3rd, 2017; Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki, David Lewis, Manual of Section (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016); Atelier Bow-Wow, Graphic Anatomy (Tokyo: Toto, 2007).

2 See: Esin Komez Daglioglu, ‘The Context Debate: An Archeology’, Architectural Theory Review, 26.06.2016.

3 Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia 2, tlk Brian Massumi (London: Athlone Press, 1988), 408