Designation of the status of a valuable individual object in a spatial plan could be considered as a reference to an architectural value that should not be unknowingly destroyed and that will be provided with specific conditions upon issuing the building permit or the design provisions.

Alongside the concept of areas of cultural and environmental value, the Planning Act entering into force in 2015 includes also a new term “valuable individual objects”. The explanatory memorandum accompanying the act provides no explanation to its content, thus, I will hereby attempt to uphold the tradition and analyse the possible ways to interpret and implement the new concept in hindsight and in the form of an article.1

A valuable individual object as a mini-area of cultural value

The areas of cultural and environmental value included in the Estonian legislation since 2003 has become a widely-used planning tool regulating the construction in areas with valuable historical buildings both in cities and in the countryside. Although areas of cultural value are mainly housed with buildings from the Tsarist or the interwar period, it is no longer a surprise to come across also more recent heritage in the given areas. To the best of my knowledge, the area of cultural value with the most recent architecture may be found in Harku municipality – the pyramid buildings constructed in the early noughties.

The vast differences in what is permitted or prohibited in areas of cultural value depend entirely on the fastidiousness and competence of the local government – the decision is made on the local level with no involvement of the National Heritage Board. Some complaints have been heard in Tallinn saying that the requirements in built-up areas with cultural value are even stricter than in national heritage conservation areas while it may happen in some other local governments that the most important historic buildings in the areas designated with cultural value are allowed to be demolished.

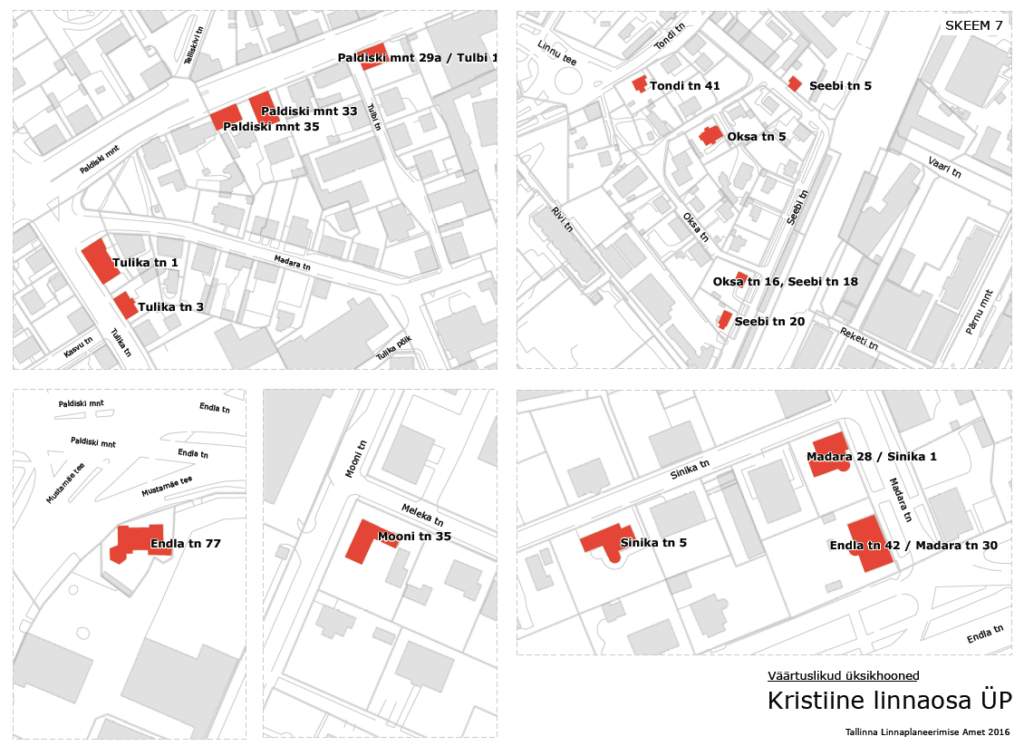

In recent years, a number of spatial plans stood out for their one-building areas of cultural value that do not quite fit the definition of a built-up area of cultural value as an “integral environment”. One of the reasons for the concept of a “valuable individual object” was to legalise the practise of one-building areas of cultural value by providing it with its own term and basis within the law.

What is permitted and prohibited is again decided entirely by the local governments much as in the case of larger areas of cultural value. Overall, the valuable individual objects could be treated similarly to the valuable buildings in areas of cultural value, as by their very nature, they should be classified no less than in the same value category.

A valuable individual object vs a proposal to place an object under protection

The common practise in the noughties was to accompany comprehensive plans with numerous recommendations to place buildings under protection which were never realised as there were no expert appraisals needed for it and, let’s be honest, the National Heritage Board has no such resources to proceed hundreds and thousands of buildings at once either.

The comprehensive plan of the city of Pärnu alone included a proposal to designate around 300 buildings as architectural monuments and, on the whole, there must be thousands of similar proposals in various comprehensive and detail plans. On the one hand, it is only admirable that we have such a large quantity of valuable cultural heritage and that planners recognise it. On the other hand, the overwhelming amount of such proposals in the spatial plans has generated ambiguous unawareness and constant inquiries, such as: do you intend to place the building under protection or can it be demolished?

Heritage protection and demolition are by no means the only options. Instead, these could be regarded as the two extreme ends of the spectrum allowing numerous other possibilities in between, including the renovation work on buildings based on reasonable resource efficiency (especially the instinct of self-preservation of buildings with individually privatised flats), the built-up areas of cultural value designated by spatial planning (local protection), the owners’ emotional ties with their ancestors’ heritage (the so-called owner’s protection) and now also another possibility for local protection in the form of valuable individual objects.

Instead of making proposals in the planning to place some objects under protection, it is now possible to designate the given buildings as valuable individual objects. It is considerably more specific than the recommendation for an architectural monument as the conditions for the protection and use can be imposed immediately with no need to wait if and when the object is taken under protection. At the same time, it is also considerably more flexible and softer than the national heritage conservation as it can be amended and specified with the next planning and why not even cancelled in case there is an urgent need to expand a road, military base or even the zoo.

With the given concept, the local protection left out of the Heritage Conservation Act in 1993 is basically restored in the Planning Act. The decisions regarding the designation of local protection are taken to the level of spatial plans adopted by the local government as it is commonly done in the Nordic countries. It brings about some confusion but at the same time also shared responsibility – broad-based heritage conservation that does not rely merely on a handful of state officials but also becomes the interest of the local governments and communities.

An old building vs street extension

The designation of valuable individual objects is inescapably accompanied by the good old dilemma of preserving historic buildings and widening streets, as older houses often extend over the building line of the more recent buildings – on the street line before the cars.

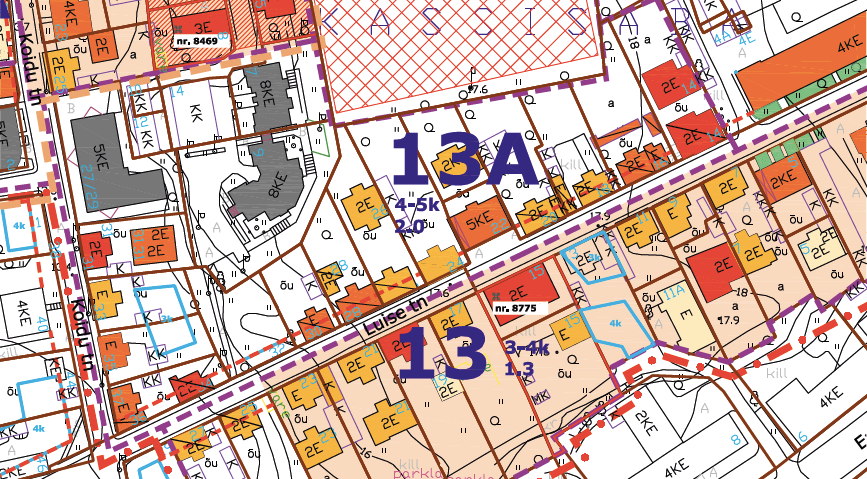

The drafting of the thematic plan of the areas of cultural value in Tallinn city centre solved the issue by designating the buildings along the street in need of widening as valuable, however, the new building line in the thematic plan was drawn across them, in other words, the buildings were to be preserved only until an opportunity arises to widen the street. The most striking example is Luise Street where altogether 16 old houses have been deemed to be demolished in the area of cultural value pursuant to the building line of the two more recent buildings.

All the old buildings are naturally still intact and no streets have so far been widened in the areas of cultural value in Tallinn, quite the contrary, some streets have actually been narrowed down to make more room for pedestrians. Now there have also been talks about making Luise Street narrower and calmer similarly to Soo and Tehnika Streets.

Considering the contemporary trends in the urban street design with recommendations to calm down the traffic in straight wide roads and to bring them down to the human scale by articulating them with various artificial bends and reductions in width, the widening of streets for the sake of increasing road capacity should no longer be the primary goal.

If we no longer consider the street primarily as a transport corridor but as a space where it is pleasant and interesting also for pedestrians, the building front of various age and exterior with alternating setback lines should be preferred to the straight and uniform row of buildings. The daily street life leaves no doubt that people in Tallinn prefer to walk in the meandering streets of the Old Town and wooden housing districts instead of the wind tunnels of Narva and Tartu Roads.

We no longer need to worry if the preservation of this or that building is really so important that the street widening should be abandoned – instead, we could ask if it is reasonable to make the roads with the current housing wider and faster and then add artificial bends and bumps to calm the traffic down again. The houses currently stepping over the building line make the road narrower and curvier in a natural way while also creating shady nooks in the urban space for a café terrace, bike rack, green hideaways and other objects diversifying the public space.

Several historic buildings are said to have been left without protection since various street extensions and grade-separated junctions were planned to replace them during the revision of the list of cultural monuments in 1990s. For instance, the summer manor of Wittenhof was to make way for a two-level junction already long ago, and in order to avoid any impediment to the construction of the interchange that was considered highly important at the time, the given building was not listed among monuments of cultural value. Times have changed – the dream of a two-level junction in place of the summer manor has been discarded and the building is designated as a valuable individual object in the comprehensive plan.

What can be designated as a valuable individual object?

The status of a valuable individual object in spatial plans can be any object or structure that deserves to be preserved in the given planning area. About half of the churches and the main buildings of manor complexes in Estonia are not under protection, let alone windmills, lighthouses, schools and community buildings with a considerably smaller proportion of objects under heritage protection. They all definitely have a high cultural value, at least in the local context. In addition to buildings, also monuments, remarkable cobbled streets, parks, bridges etc could be designated as valuable individual objects.

The given designation in the plan could also be considered as a reference to something important and valuable so that it would not be unknowingly destroyed. If it is considered as an informative note that forms the basis for the specific administrative decision only at the issuing of the design provisions or building permit, it should not give rise to any particular planning disputes.

Especially in devising a detailed plan, it should be self-evident that an analysis is conducted of the possible valuable buildings in the area and the possibilities to preserve them, much like an evaluation is always given to the respective tree. In case of buildings, replacement plantings are unfortunately not possible: once it is decided in the detailed plan to have the structures demolished, they will be gone for good even if the building becomes a popular meeting place after the adoption of the plan – our detailed plans are valid forever. In earlier detailed plans, the valuable buildings are often very carelessly overridden. For instance, in case of the recent controversy over the restaurant Umami, the detailed plan allowing its demolition (initiated in 2004, adopted in 2008) mentioned the villa from 1920s only in the following wording: “There are some small buildings in the plot covered by the detailed plan. There are no large buildings.” Hopefully, the possibility to designate valuable individual objects in the planning area will encourage planners, local governments and also communities to come together during the planning proceedings to discuss if the demolition of the area is the best solution or perhaps some of the current layers could be preserved. After the decision of the detailed plan adoption is made, such discussions are unfortunately entirely futile.

Historic buildings in the protected zone of architectural monuments and heritage conservation areas

The architectural monuments and heritage conservation areas under state protection are surrounded by protected zones. In addition to ensuring the observability of the architectural monuments or heritage conservation areas, their task also includes the preservation of constructional elements of cultural value of an immovable monument, heritage conservation area and the surrounding area thereof in the context of space. In case we wish to implement the given sentence with utmost rigour, it would be theoretically possible to prohibit any kind of new buildings in the protected zone as the context of space would change with every alteration. In practice, however, we see the other end of the spectrum with valuable historic buildings in the protected zone allowed to be demolished as they are not under protection.

The protected zone is not a building exclusion zone, but it should not be a zone of random demolition either. The line between the heritage conservation area and the protected zone often runs along the street – on the one hand, it is a clear divide between the different possibilities to implement the various sections of the law but it would be quite odd to demand that the home owners on one side of the street install wooden windows with ironwork details sealed with tow while buildings of similar age and value across the street are allowed to be demolished. The same applies also to the border areas of the built-up areas of cultural value.

The addition of valuable individual objects in the Planning Act is a clear signal that also buildings that are not designated as architectural monuments or located in a heritage conservation area can be valued. In protected zones as areas where it is important to preserve structural elements of cultural value, the self-same concept of a valuable individual object can help to preserve historic buildings by means of plannings in order to maintain the perceivable transitional area between the heritage conservation area and the new developments.

Is there now too much protection?

We have national monuments and 12 heritage conservation areas, an indiscernible number of built-up areas of cultural value and now also valuable individual objects. Some people may ask if there isn’t too much of it already and soon perhaps nothing is allowed anywhere?

The unduly restrictive and indiscriminate implementation of the law is a real danger, however, the inclusion of supplementary concepts in the law does not increase the possibility much. It may be complained that heritage conservation is restrictive and the rules of the built-up areas of cultural value are inflexible but, in fact, we can find considerably more restrictive building conditions in areas with no apparent official restrictive zones. For instance, the thematic plan presently devised by Vormsi local municipality only allows the construction of buildings with a symmetric gable roof of an angle between 35-45 degrees. Hip roofs, half-hipped roofs, mansard roofs etc are not permitted. There is considerably more freedom in designing new buildings in both heritage conservation areas and, as far as I know, in built-up areas of cultural value. The comprehensive plan is the mutual agreement between the local government and the community, and as long as the local people agree to such a fastidious approach, everything is fine. This merely illustrates that it is possible to impose highly strict limitations to construction also with no state or local protection, even significantly stricter than the ones applying to Tallinn Old Town that is included in the UN World Heritage list – here we even see new buildings with a flat roof!

The so-called local protection of individual buildings outside the built-up areas of cultural value is actually nothing new, it is at least a common practise in Tallinn implemented by the issuing of design specifications that consider the architectural value of the building. In fact, last year for the very first time, Tallinn City Government acknowledged a well-restored building that is not under protection nor in a built-up area of cultural value – Kentmanni 20a. The design provisions of the building excluded the tampering of the façade and the result is indeed very good. Mapping valuable individual objects in the spatial plan allows the indication of similar buildings in need of increased attention early on so that it would be foreseeable for the owners and a good basis for the officials.

Decisions, decisions

What should be designated as a valuable individual object and what not, when should the preference be given to the street widening and when to the preservation of current buildings – this is naturally an endless issue of consideration with no clear answers. However, it must be mentioned that if the decision is not made so to speak arbitrarily by the local official in consideration of the specialists’ evaluation, it will be made arbitrarily by the form of ownership.

The entire Soviet layer of buildings in Tallinn city centre from Kaubamaja department store to the office building at Rävala 8 along with the row of buildings at the beginning of Estonia Avenue is rapidly disappearing. Only a couple of architectural monuments will remain and all apartment buildings. They are by no means in a better technical condition or with better building quality or architectural value than the office buildings from that era – quite the contrary. However, unlike other building types, the individually privatised apartment buildings have a keen sense of self-preservation that grows with every new homeowner and small investment accumulated in in the flats.

Any attempt for preservation, including the designation as a valuable individual object is in broad terms merely an effort to balance out the weighing pans tipped by the pot luck of the ownership reform and to bring also the architectural and historic value of the building to the decision-making table.

TRIIN TALK is a restorer and heritage conservationist, former Inspector-General of Architectural Monuments of the National Heritage Board.

HEADER photo by Reio Avaste

PUBLISHED: Maja 96 (spring 2019), with main topic Spatial Diversity

1 Martti Preem „Miljööalad – mis ja milleks“, (Areas of Cultural Value – What and Why?) journal Maja 3/ 2008. http://www.arhliit.ee/uudised/artiklid/miljooalad/