EXPERIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE

Humbly Majestic. Arvo Pärt Centre 〉 Triin Ojari

The Super Transformer. Elering 〉 Karli Luik

A Monumental Enigma. The Narva College of Tartu University 〉 Carl-Dag Lige

Continuous Strangeness 〉 Merilin Kaup, Mariann Tihane, Liina Soosaar

Vana-Vastseliina Pilgrim’s House 〉 Karen Jagodin

Architecture That Invites You to Move 〉 Terje Ong, Risto Kozer

Wasteland 〉 Paco Ulman

Weak Monument – What For? 〉 Kaja Pae

A Catalogue of Good Taste 〉 Kaja Pae

Karlova Obscura 〉 Johan Huimerind

PERSONAS

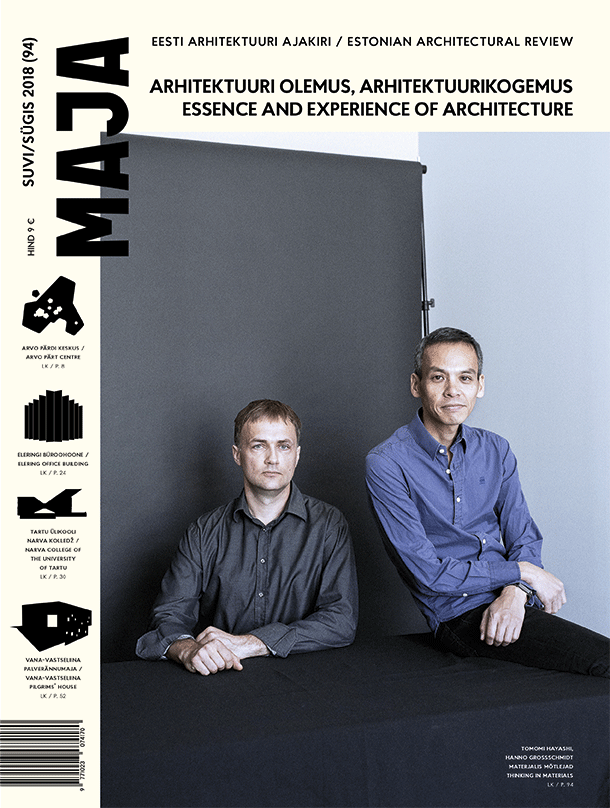

Tomomi Hayashi and Hanno Grossshmidt. Thinking in Materials 〉 Kalle Komissarov

ESSENCE OF ARCHITECTURE

Four Spaces 〉 Anu Vahtra

Of the Obscure Component 〉 Indrek Rünkla

Pleasure of Beauty 〉 Yael Reisner, Siim Tuksam

But Why 〉 Siim Tuksam

Of the Measurable and Unmeasurable in Architecture 〉 Urmo Mets

These Walls, They Talk 〉 Marianne Jõgi

Shelters and Forest Cabins – from Polemical Approach to Media Machine 〉 Alvin Järving

Houses as Zones 〉 Sven Vabar

ESSENCE AND EXPERIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE

A number of decisions are made during the creation of architecture that the architect does not verbalize or rationalize, and usually doesn’t discuss later either. Today, we tend to speak about architecture either “above its physical scale” – discussing its functionality, social impact, role in urban space or similar factors, or “below its scale” – architecture is seen as something that consists of materials, surfaces, economical construction units. Of course, both of these scales are important and reflect the reach of architecture, but justifying the usefulness of architecture via these aspects, one might start to think that non-verbal decisions are random or not so significant. However, every architect knows that in cases of powerful outcome, they are the backbone of architecture, without which their creations won’t stand on their own two feet. The desire to speak about objects of architecture at the level of the object itself – its influence, aesthetics or beauty – is rarer that we might think.

The first half of the magazine takes a look at the experience offered by specific architectural objects. Carl-Dag Lige writes about the phenomenon of the building of Narva College, completed 6 years ago, and its impact on Narva and its people – there could be more retroactive architecture criticism like this in Estonia. What does the recently completed Arvo Pärt Centre offer us and does it meet the high expectations? Triin Ojari gives her opinion on this.

The second half of the magazine probes the depths of the work of an architect and touches the essence of architecture. A couple of thousand years ago, Vitruvius formulated the issues of creating architecture as follows: “Wherefore the mere practical architect is not able to assign sufficient reasons for the forms he adopts; and the theoretic architect also fails, grasping the shadow instead of the substance. He who is theoretic as well as practical, is therefore doubly armed; able not only to prove the propriety of his design, but equally so to carry it into execution. /…/ Like all areas, architecture also has two sides – the idea and its expression. The idea is spoken of and expressed by means characteristic of scholarship. Anyone who wants to call themselves an architect must know both sides. /…/ He should be a good writer, a skillful draftsman, versed in geometry and optics, expert at figures, acquainted with history, informed on the principles of natural and moral philosophy, somewhat of a musician, not ignorant of the sciences both of law and physic, nor of the motions, laws, and relations to each other, of the heavenly bodies.”

These paragraphs remind us how difficult it is to combine abstract thinking and practical outputs, how easy it is to get stuck in the one that feels more natural and how essential this art of combination is for the birth of great architecture. The word that Vitruvius uses allows us to understand the word translated as “idea” not only as rationality, but as anything that manifests itself.

Like multilingual people may switch languages according to the topic, architects switch from thinking in the visual language to thinking in the verbal one. Architecture is what architects do, said British architect Cedric Price. This definition, which seems trivial at first, no longer makes it possible to question whether the amazingly graphic illustrations of Daniel Libeskind or the cosmic paintings of Zaha Hadid are architecture. They are also a step in the development of their personal language. Architects themselves are not eager to translate their creative language into words, many of them preferring to consider it untranslatable and hiding behind a veil of secrecy. A young architect at the start of his or her professional life after graduating from the academy, who has only learnt to defend their project in front of professors who silently understand their graphic specialist language, may find him- or herself facing the question of how to discuss this with people who are not architects. How do you speak about the diversity of architecture, the decision-making process, including its obscure parts? The first article of the second half by Indrek Rünkla also tackles this question. Yael Reisner,the main curator of Tallinn Architecture Biennale 2019, shows how to bring talking about beauty back to architecture and why this has been overshadowed by rationality.

The diversity of the architectural languages and switching between the languages used to create architecture are some of the most fascinating parts of architecture and nevertheless, as also writes Yael Reisner, an architect instantly recognises the moment when everything falls into place, in sense of all possible translations.

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae

October, 2018