Andres Sevtsuk is a Professor of Urban Science and Planning at the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, where he also leads the City Form Lab. Maroš Krivý is a professor of Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts.They shared their insights on current state and challenges of Estonian architecture.

What are your observations about recent Estonian architecture?

Andres Sevtsuk:

I think Estonian architecture has really matured in the last decade. There has been a considerable leap in detailing and the quality of construction. While the 1990s and maybe early 2000s were characterized by conceptually very interesting work but poorer technical quality, we now see more projects that are both conceptually interesting and technically well executed.

Estonian architecture and urban design appear to share commonalities with Northern European regional particularities. There is considerable interest in quality public spaces and public projects—libraries, schools, day-care centres, sports complexes, concert halls etc.—which are receiving new and notable buildings. This is largely thanks to state commissions and funding, but such projects are also defining a new modern landscape in smaller cities across the country. But unlike Scandinavian counterparts, there are also more interesting post-soviet sensibilities that come through in the projects (e.g. the Estonian National Museum, Aparaat (Widget factory) or Tiit Sild’s Garage Residence in Tartu). We seem to be finally valuing, or at least exhibiting, the recent decades of Soviet history through contemporary design.

Historic references and a more acute context sensitivity have also more generally crept back into architecture and urban design. Kavakava’s work offers perhaps the most poignant examples—many of their projects seem to be driving by an urge to create a dialogue with place history (e.g. Tartu Health Care College, Narva College, Tallinn Main Street). But unlike historic motifs in post-modern architecture, we are now dealing with more nuanced, less iconic complexity and contradiction in architecture. I think Alver, Trummal and Kaasik’s views from the 1990s helped to pave the way for this (i.e. De la Gardie shopping complex, Freedom Square).

Finally, we have to also admit that market interests have co-opted architecture that attempts to communicate history and complexity. Districts like Rotermann Quarter and Noblessner, which are visually stunning and historically complex, have been strangled by blatant capital greed. Their architectural diversity is not matched by socio-demographic or functional diversity. Rather, the most socially diverse spaces are architecturally completely mundane shopping centres on the urban edge.

Are there any unique features about Estonian architecture and spatial culture that you would like to point out? What are the values of Estonian architecture to draw attention to?

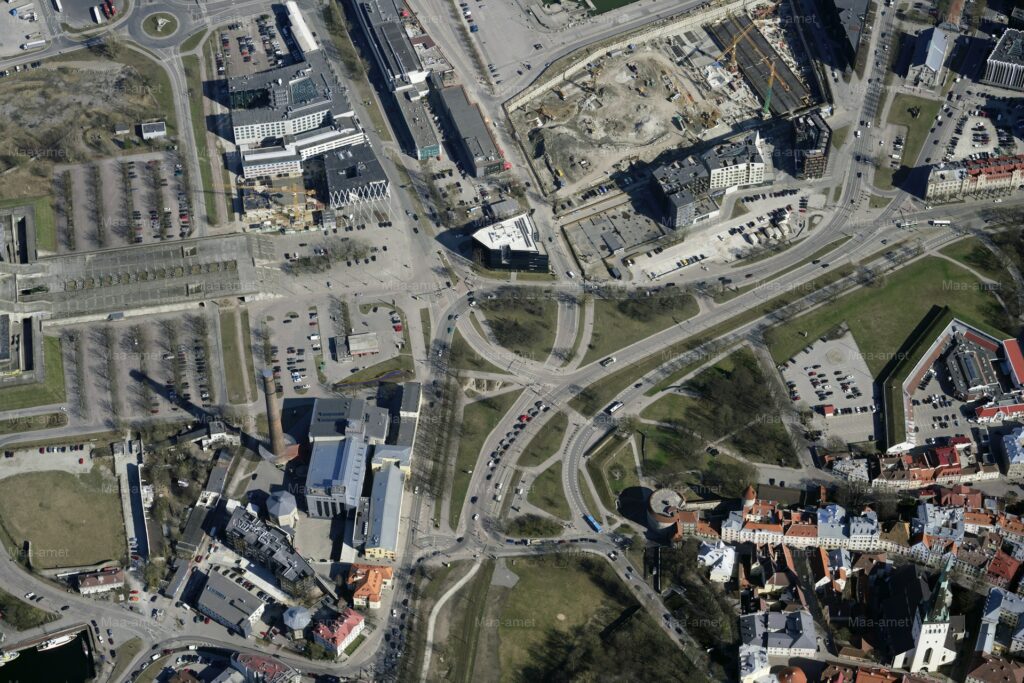

I think Estonian cities are uniquely characterized by a series of unfinished megaprojects from the past. Tallinn in particular has a complex urban fabric, full of historic discontinuities—Rävala Boulevard, City Hall, rather poorly used Bastion Belt, and highly contrasting residential plattenbau districts like Lasnamäe.

What stands out even more from the last ten years is the government’s greater emphasis on virtual space than on physical space. Estonia has become world-renowned for its e-governance solutions that provide a great deal of convenience to everyday transactions between people, institutions, companies and government. At the same time, the physical public spaces have been less of a priority. When I remarked above that a series of architectural projects, largely commissioned by the government, have helped re-energize town centres across the country with modern icons, the same cannot be said about typical streets and public spaces. Instead, the Estonian street-scape has been increasingly defined by motorization and car culture. Traffic engineers dominate street renovations and the vast majority of public sector transportation investments have targeted vehicular traffic, not public transport, pedestrian or bike improvements. This is one of the reasons that the profession of landscape architect still remains undervalued in our society.

What are the most interesting contemporary Estonian buildings/urban projects/architectural activities or events for you and why?

I will mention six projects that have personally affected me in the last decade, in no particular order of importance.

Baltic Station Market (KOKO Architects) for re-introducing a beloved and time-tested activity—open air market—to the city with contemporary twist and at a great location.

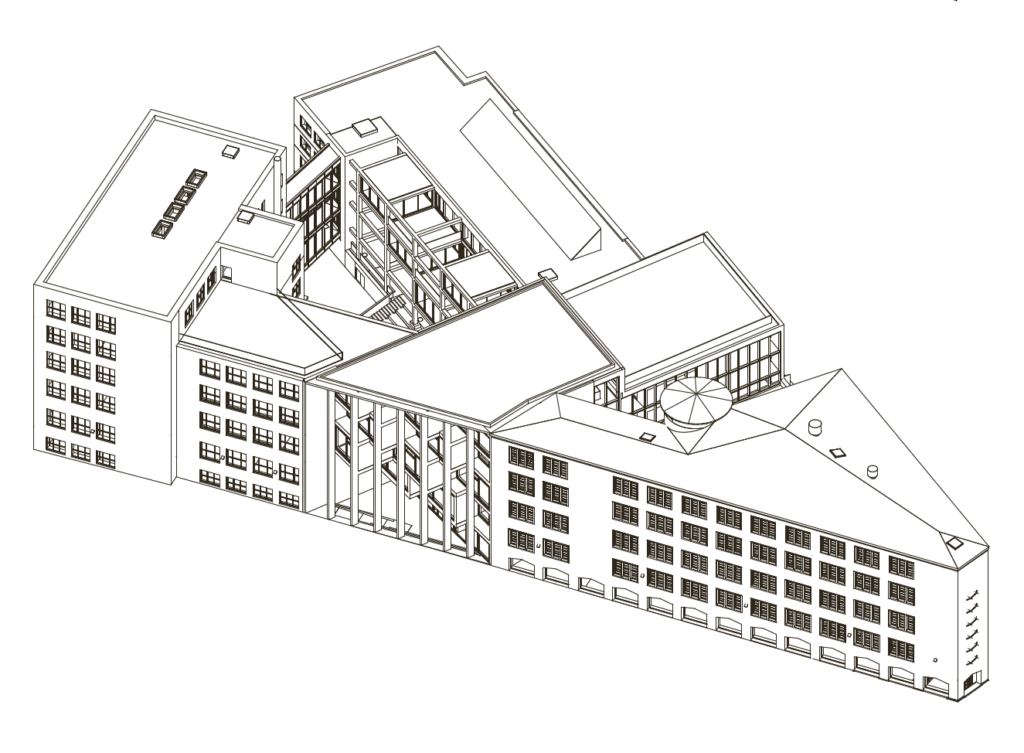

The renovation of the Estonian Academy of Arts (Kuu Architects and Eik Hermann) for demonstrating a creative and sensitive approach to reusing historic buildings not as soulless museums but as energetic environments for contemporary thought.

The renovated public promenade of Annelinn in Tartu (Tajuruum, vision process curated by Kaja Pae) for showing us that no place is hopeless.

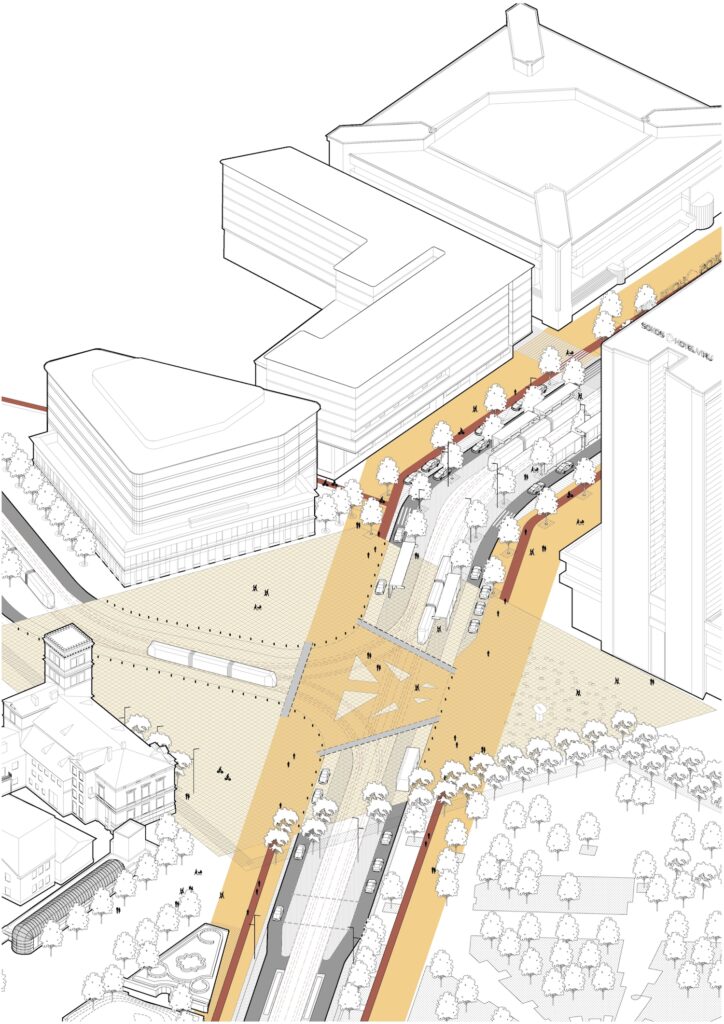

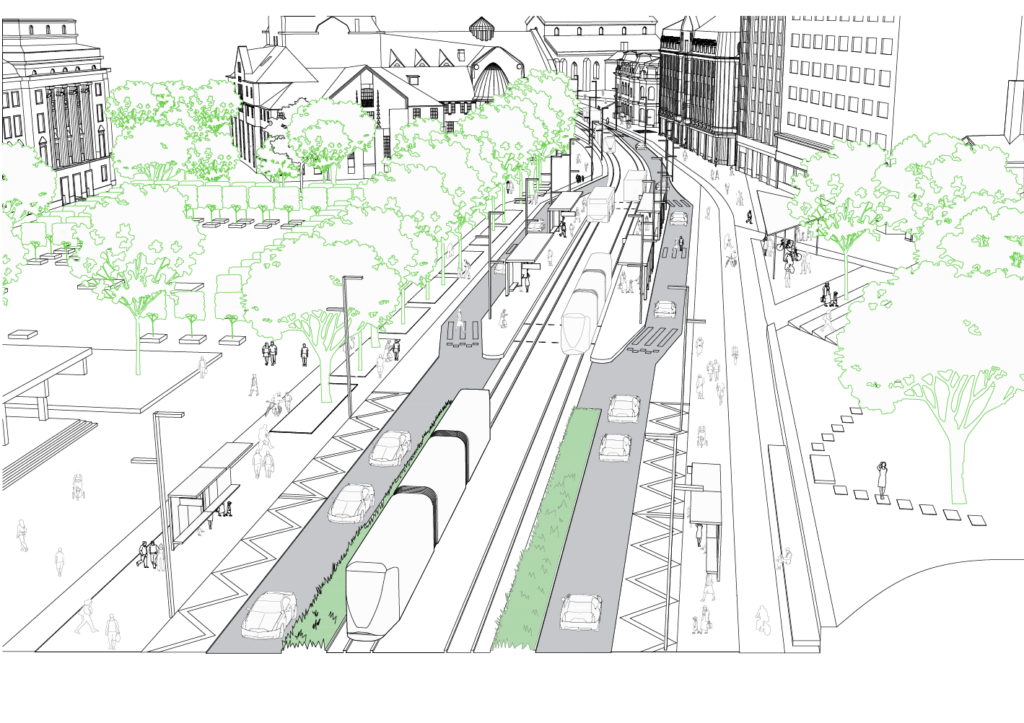

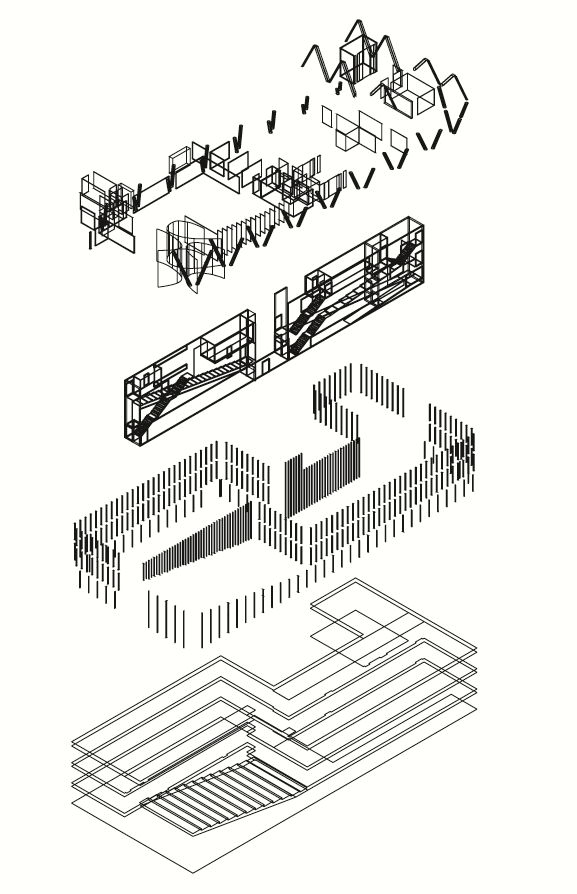

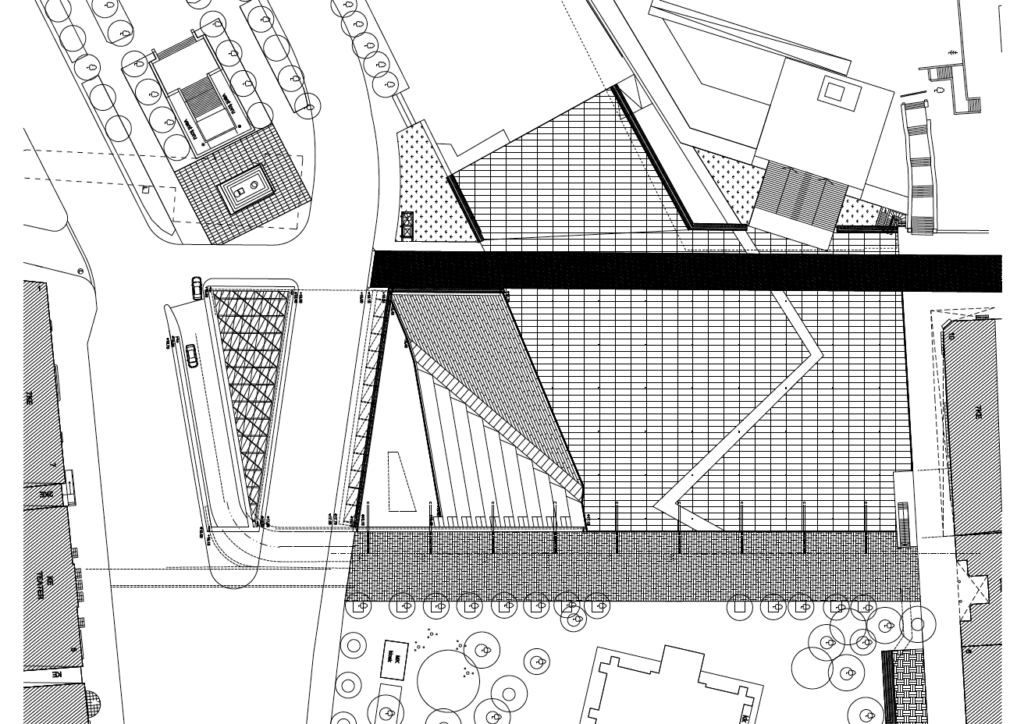

Tallinn’s Main Street project (Kavakava Architects and Toomas Paaver, prior process curated by Tiit Sild) for showing the kind of care that should ideally go into every street in the city.

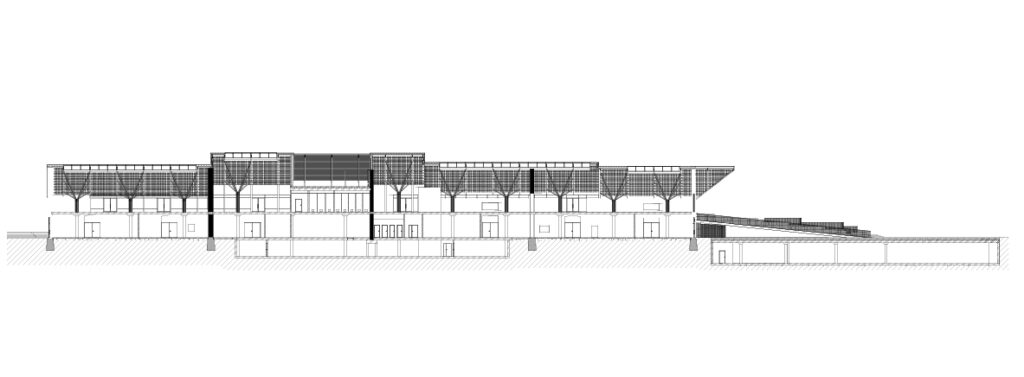

Pärnu Library (3+1 Architects) for its unapologetically modern yet context-sensitive and delicate insertion of public values into a historic city centre.

Toomas Tammis’ house in Tallinn for redefining public-private relationships in a typical courtyard of a historic perimeter block.

What are the current challenges for Estonian architecture?

I think good environmental design requires both construction craft – the tactile know-how of making quality objects — and an intellectual grounding that breathes identity and meaning into the objects. Mens et manus, like the slogan of my home university MIT states. I think we are currently doing pretty well on the craft side of architecture in Estonia. Even conceptually, the architecture of the last decade is often interesting and compelling. But I think we have some distance to go towards a more theoretically grounded architecture.

Sure, we are blessed to have a remarkable set of local, young and talented architecture critics — Andres Kurg, Ingrid Ruudi, Carl-Dag Lige, Triin Ojari among others — but we have fewer practicing architects who also theorize about their work. We had Alver, Trummal and Kaasik as well as Künnapu doing some theoretical writing in the 1990s and their views certainly influenced the course of Estonian architecture throughout the past two decades. But who are the practicing architectural theorists today? I think it will be important for Estonian architecture to promote more intellectual approaches to design and more theoretical work as well.

I also think we have room for growth as a society in developing an urbanistic culture — a set of basic shared understandings and ideas of whether and how the design of the built environment matters to us all and which types of design approaches work best towards tackling contemporary urban challenges. All too often, even our political leaders appear to lack the basic understanding of how urbanistic decisions are interlinked and what externalities or consequences certain choices can bring in the longer term. I think we will slowly but steadily build up a more mature urban culture, where even the average informed discussant will have a rather nuanced and complex understanding of urban phenomena. Countries like Holland, Finland, France, Germany and Switzerland are still far ahead in that regard but we will get there too. I am encouraged by the vibrant public argumentation and debates we are seeing over large projects in the media these days.

What are your observations about Estonian architecture? Are there any unique features about Estonian architecture and spatial culture that you would like to point out?

I moved to Tallinn in 2012, when I was invited to manage and develop the Urban Studies program at the Estonian Academy of Arts. I have thoroughly enjoyed the experience so far! The changes that struck me most relate to urbanism and the way in which architects think about and intervene in space: the significance of ethno-cultural nationalism to architectural culture; late-socialist postmodern architecture influenced by regionalism and brutalism; gentrification driven by deregulated real estate and historic preservation; and the simultaneous stigmatization, regeneration and “rediscovery” of socialist mass housing neighbourhoods.

I would describe contemporary Estonian architecture as a blend of pragmatic neo-modernism, introverted expressionism, and what can be described as an industrial-chic style. I would situate it on the intersection between, on the one hand, the imaginary Nordicness focused on simplicity, convenience and comfort, and symbolized by crisp, clean compositions enveloped by nature (the forest, lake) and, on the other, the reality of the neoliberal transformation driven by financial and real estate capital, which is continuous with uneven urban development and the absent debate on social equality and justice. The ways in which contemporary architecture in Estonia produces, transforms and reflects desirable styles of life illustrates the fact that Estonians have looked to Nordic countries as to the imaginary West. Even as this architecture rediscovered the value of urban density and urbanity, in its symbolic expression it turns towards the utopias of the non-city: the historicizing one of untouched nature, and the forward-looking one of digital networks. Architecture and spatial culture in Estonia could be characterized as a complex process of negotiating these expectations and realities.

What are the most interesting contemporary Estonian buildings/urban projects/architectural events for you and why?

I will use the term “interesting” not in the sense of good or bad but to refer to objects/events that I think register or speak to contemporary socio-political developments. I have been very interested in the process of transforming Kultuurikatel and the surrounding area, and how contrasting conceptions of culture have been manifested in this process.

I want to mention one particular aspect of this process of which Kultuurikatel is a good example, and that is the popularization of the industrial-chic interior style in the context of smart economy narratives. My article “The Smart and The Ruined”3 explored, through the case study of Kultuurikatel, the interior style focused on exposing corroded surfaces, defunct industrial machinery and battered walls. Why is such a style compelling in a factory renovation project? I have suggested that it provides a symbolic backdrop to what the Italian political philosopher Paolo Virno calls “social factory”, a form of capitalism where value production is dispersed across the entire social body. The kernel of social factory is the entrepreneur of the self4, and I think the unflinching belief in Estonia that start-up economy and the digital future will do wonders provides a fascinating image for the concept.

I was struck by the use of Kultuurikatel in 2017 as a host venue for events related to Estonia’s EU Council presidency, especially the Digital Summit. Smartly dressed high-level officials discussed the future of digital economy surrounded by gigantic defunct boiler, while instructions how to access the conference Wi-Fi network entitled “FreeTheData” were displayed on digital panels juxtaposed against the pockmarked, graffitied walls.

My suggestion is that Kultuurikatel and other carefully restored industrial ruins — restored as images of ruins — can be seen as retroactive monuments to the fancied heroism of the digital age, whose infrastructural components — underwater sea cables, the Global South’s rare-earth metal mines, or e-Estonia’s servers — are devoid of monumental symbolism, and it is unlikely they could be monumentalized in any collectively meaningful way.

The struggle around the use of adjacent Kalarand, where activists contested a private luxury project, is another interesting case — sadly now only as a historical study. However, it continues to speak to the challenges of urban activism in a post-socialist context. The activists embraced the designation “wasteland”, which was seen as a positive marker of socio-environmental alterity. Assimilating the site’s spontaneous ecology, Kalarand was thus a kernel of an alternative public — self-organized from the bottom up. Yet the case also illuminates the limits to post-socialist urban activism in Estonia in that there is a lack of capacity to articulate these concerns in terms of inequality and power. It is wonderful that urban wastelands have evoked interest as spaces of alternative politics and ecology, however, Tallinn urban activists have not so far been able to address how class, ethnic or gender relations shape the capacity to appreciate wastelands as interesting, valuable or generally beneficial (which is what justifies calling it post-socialist). Such activism runs the risk of exacerbating green gentrification and playing into the hands of real estate developers, who have turned to “wasteland aesthetic” as an urban design trend.

I would also say that one very interesting contemporary project is Tallinn. This is not only to highlight that all projects are based on a certain idea of the city and they negotiate the interface between architecture and the city but also to appreciate the way in which the urban has become again a challenge in the Estonian architectural arena. While for the time being, the urban question has been posed primarily as a question of urban design, physical public space and urban platforms, it is to be hoped that the intellectual traffic between the fields of architecture and urban political economy/ecology will increase in the future. The question of power relations in the neoliberal city should be put on the table. Architects cannot avoid asking if we want more or less equal cities? And what should be done about it?

Regarding events, I would definitely highlight the Baltic Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale. This was interesting for several reasons: bold conceptual approach, urgent theme and impressive use of space. The pavilion also challenged the habit of thinking architecture in national terms. What does the qualifier “Estonian” (or “Latvian”, “Finnish”) mean when it is applied before the word “architecture”?

If you press me to mention one object that is not only interesting to me but that I also thoroughly enjoyed, it would be the now-closed Patarei café (definitely not pop-up!).

Interviewed by Kaja Pae, Maja’s editor-in-chief 2017-2022

Header: The Estonian National Museum. Dan Dorell, Lina Ghotmeh, Tsuyoshi Tane (DGT Architects), 2016. Photo: BTH Studio

Published in Maja’s 2020 spring edition Maja 100! (No 100).

1 The EU funded EV100 town square renovation program offers a noteworthy exception.

2 Alver, A., Kaasik, V., & Trummal, T. (1999). Üle Majade. Alver & Trummal Arhitektuuribüroo. p. 104.

3 Krivy, Maros (2019). The Smart and the Ruined: Notes on the New Social Factory. Thresholds, 47, pp. 75−90.

4 Foucault’s term ‘entrepreneur of the self’ from his lecture series “Birth of Bioplitics” (1979) stands for neoliberal, self-centered subject, outside from the social field. It conforms to the incomplete information of the market and is in constant adaptation due to the power relations of neoliberal society.