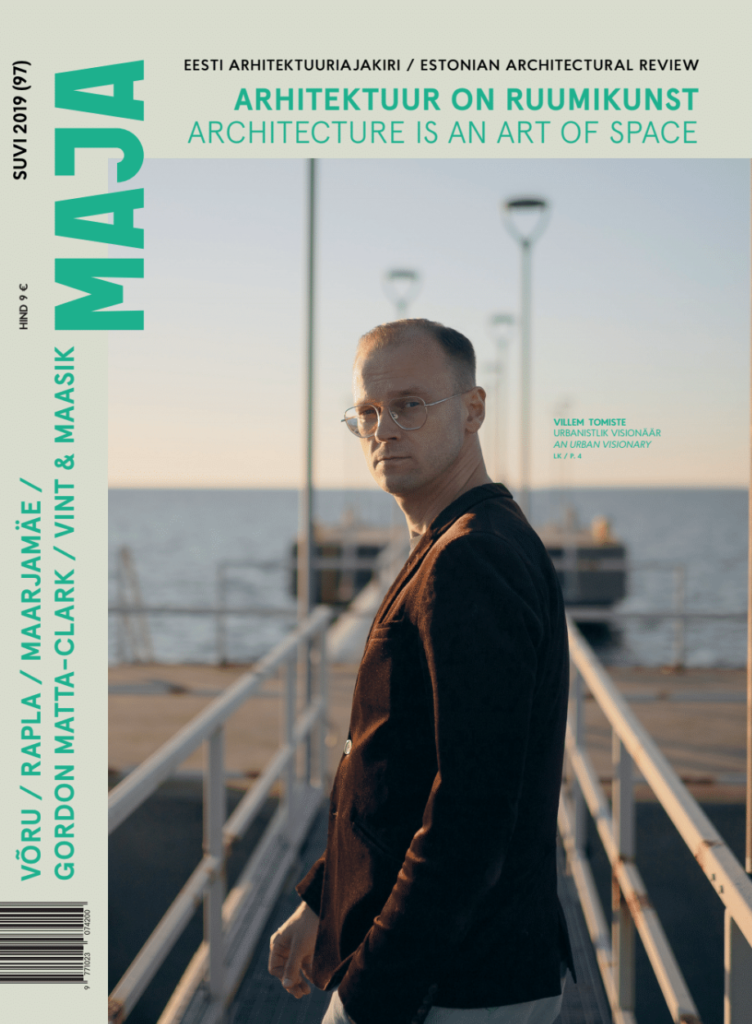

PERSONA

An Urban Visionary Villem Tomiste 〉 Interviewed by Ingrid Ruudi

AN ART OF SPACE

Move Me 〉 Maria Pukk

Streets and Squares 〉 Leonard Ma

Showdowns and Standoffs — Between Art and Architecture 〉 Kaja Pae

Enigmatical Architecture 〉 Kaja Pae

Victims of Communism Memorial at Maarjamäe 〉 Leonhard Lapin

Vint and Maasik, or, the Love of Geometry 〉 Jaak Kikas

A Photo Etude Villa Valeri II 〉 Paco Ulman

The Simple Pleasures of a Fun House 〉 Triin Ojari

Uglyness Can Sometimes Be More Powerful Than Beauty 〉 Merle Karro-Kalberg

Architecture is an Art of Space

It is not only customary to view art as inherently concealing of conflict and enigma, it is something we purposefully look for in it. These qualities are often what bring a piece to life – conditioning the work as an unsolved problem establishes a temporal dimension and a perpetuating connection to the viewer. Yet, what about conflict in architecture? How many open ends can we design into an architectural project? Is there any room for them at all? Public space entails an array of contradicting objectives and intents. The aim of public space projects is to look for ways these can coexist. Occasionally, oppositions are so deeply rooted that atoning for them and tying loose ends overtakes the entire focus, neglecting the creative side of spatial design. Decisions over practical concerns need to be made and accounted for, details require most if not all of the attention.

Yet, this space, where contradictions have been (seemingly) reconciled and everything is “in place” and “solved”, may lose its relevance in the light of new emerging necessities. The phrase, “boring Nordic public space” has found a place in our vocabulary over time. Why is it boring? Is it because attempts at rationalisation have not reached their optimal peak? Or is it because rationalisation always contains some surplus – an enigma, an unatonable standoff forever elusive from the mesh of rationalisation?

This surplus can be included and appreciated in an architectural project by an appropriate flex that grants the architecture with a dimension of art. By keenly examining the surroundings and avoiding attitudes triggered by prior knowledge it is possible to notice the vastness of contradictions, the multiplicity! That which rationality cannot perceive, can be conceived and delivered aesthetically, mediated by the optically observable, visual realm. Thus, the issue of aesthetics is not something shallow or inconsequential, but quite on the contrary. Furthermore, that which we fathom as superficial is, therefore, not harnessing the true potential of aesthetics. Aesthetical “thinking” is thus one way of sensing reality. Since it is a sensory experience, it is available to anyone and is capable of touching society as a whole. How often then, could an artistic image – an unconcealed contradiction – outweigh a rational attempt to solve and communicate?

Built architecture is inevitably making physical decisions for us because that is what it was built to do – to enable, to facilitate, to embody, to shelter… Yet, conceiving architecture can also be regarded as a means to point toward specific matters. Architectural history is rich in projects that sketch out inherent conflicts or difficulties, where the “solution” is more of a sharp postulation of an issue rather than an answer to a problem. Of course, it is not a matter of creating ostensible aesthetic displays of conflict or antinomy or making them covetable. It is a matter of their undeniable presence, which awakens us to a part of reality.

The ability to epitomise contrariness by means of an aesthetic reference can be considered a source of power for architecture – a display of contradiction can be more influential than a seeming solution to a puzzle.

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae

July, 2019