ARCHITECTURE

Architecture: Arhitektuuribüroo Studio Paralleel (Jaak Huimerind, Kadri Viltrop). Interior architecture: Pink (Tarmo Piirmets, Inna Fleišer).

Rotermann Quarter stands out for the diversity of its new-builds and reconstructed former industrial buildings. There is probably no other area in Estonia awarded with as many prizes as this one. Mathilda Viigimäe and Kristi Tšernilovksi shed light on the architectural development of Rotermann Quarter.

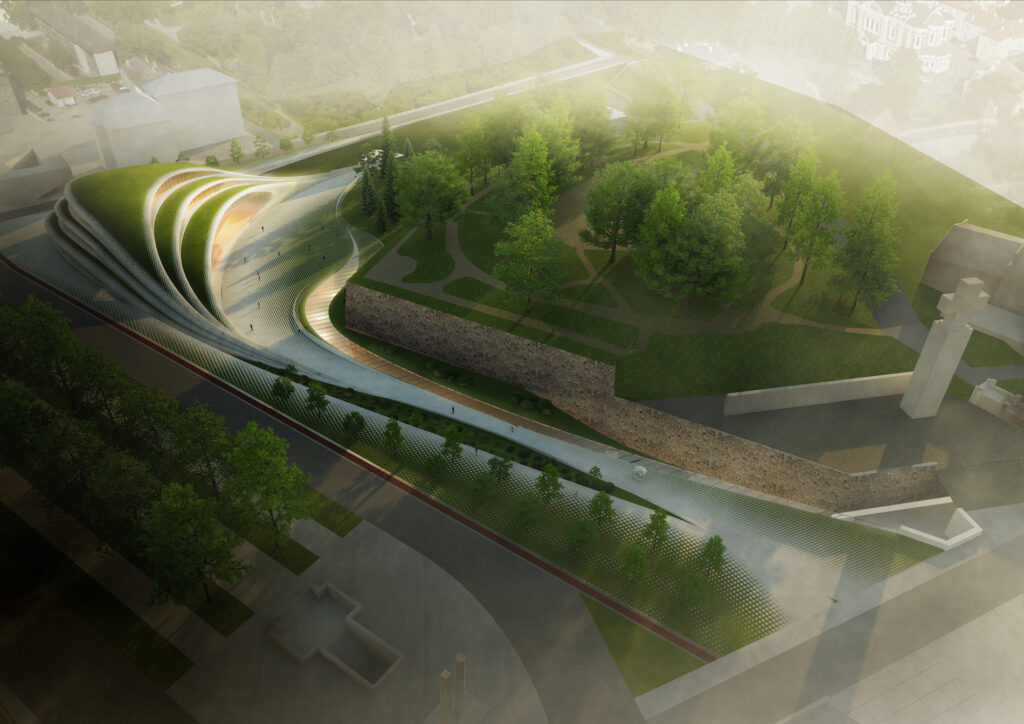

The bastion belt should be a park with its use activated by a building.

‘Heliorg’ explores the possibilities for reviving the bastion belt surrounding Tallinn Old Town.

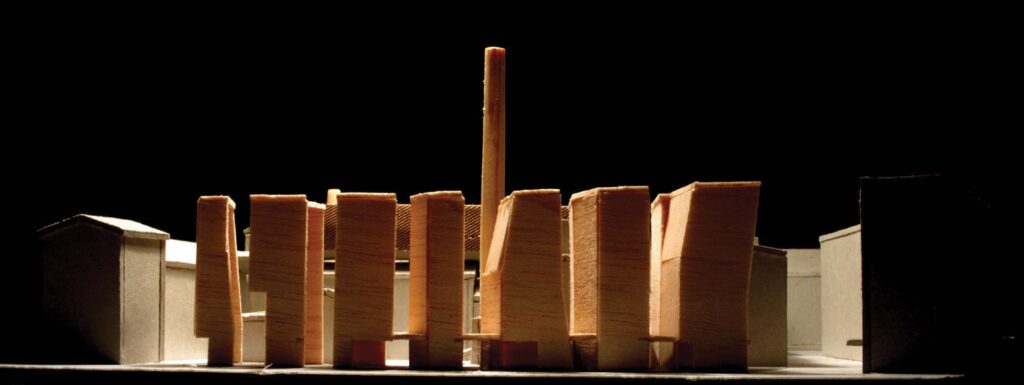

The work marks a reaction to a personal and scary experience with the highrises in central Los Angeles. When I was living and studying in LA in 2010, I imagined a dystopian degenerating city characterised by overwhelming monofunctionality pushing out the weak, increasingly higher and denser office buildings and the street space sinking into darkness.

The current work explores the role of the architect in the face of changing environmental conditions. The Arctic area is confronted with dramatic social, economic and environmental changes. The increasing pressure on the Arctic natural resources and Arctic Ocean waterways sets higher demands for the otherwise sparsely populated area. In order to ensure more efficient search and rescue competence and nature protection, a new infrastructure is needed.

The hybrid building merges the library and botanical garden into a spatial whole, a symbiosis of design and high technology. It is located in Burggarten in Vienna – the historical imperial private garden of the Habsburg family, between the Austrian National Library and Palmenhaus.

The aim of the work is to achieve harmony and universal beauty. I value milieus and particular atmospheres carrying it. Sometimes I convey it with a single line or a geometric detail that can evolve into a deeper spatial gesture.

A building with a strong character is easy to hate. Or to love. Take, for example, Tallinn City Hall—few are indifferent to it. Many see the City Hall as an ingenious artificial landscape and urban stage, while others consider it a relict of the Soviet occupation that is unfit for a free Estonia, just like the Sakala Centre that was demolished in 2007. There are many other lesser or better known buildings from the Soviet period that are architecturally ambitious, but unacceptable to many for aesthetic or ideological reasons.

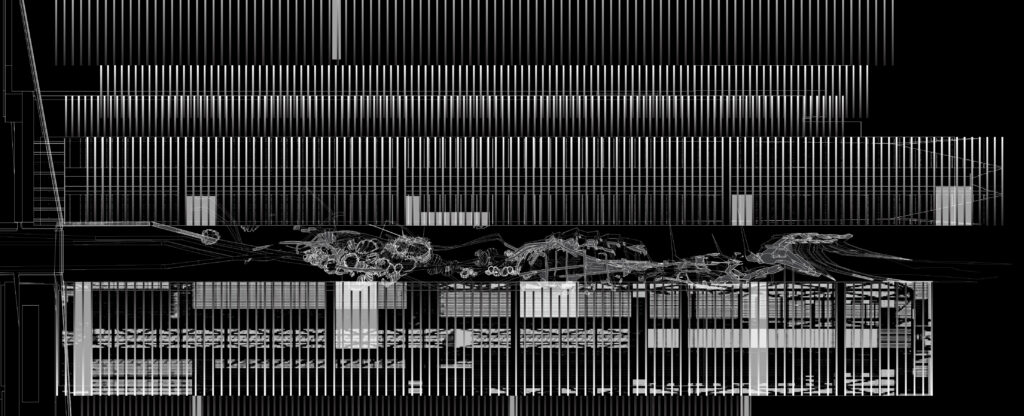

The new terminal is not just a building, it is above all an urban act, showing the way to and perhaps even anticipating the integration of the harbour and the entire seafront area.

Postitused otsas

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS