MATERIAL AND NOVELTY

How to Reach Novelty? 〉Rachel Armstrong, Manja van de Worp, Jelle Feringa

As You Call the Forest, So the Forest Calls You Back 〉 Andrus Laansalu

Not to Make a Concrete Ruler 〉 Karl-Eerik Unt

Luther Machine Room: a Temple of the Industrial Era 〉 Darja Andrejeva

The Green Garden of Building Materials 〉 Tõnis Arjus

Algorithmic Craftmanship for Bespoke Timber Architecture 〉 Sille Pihlak

The Algorithm of Craftmanship 〉 Kaiko Kivi

Digital Material 〉 Gilles Retsin

Coffee Morphoses 〉 Annika Kaldoja

Combinatorics of Local Materials on the Example of Peat and Oil Shale Ash 〉 Märten Peterson

Ground 〉 David Grandorge, Jonathan Lovekin

PERSONA

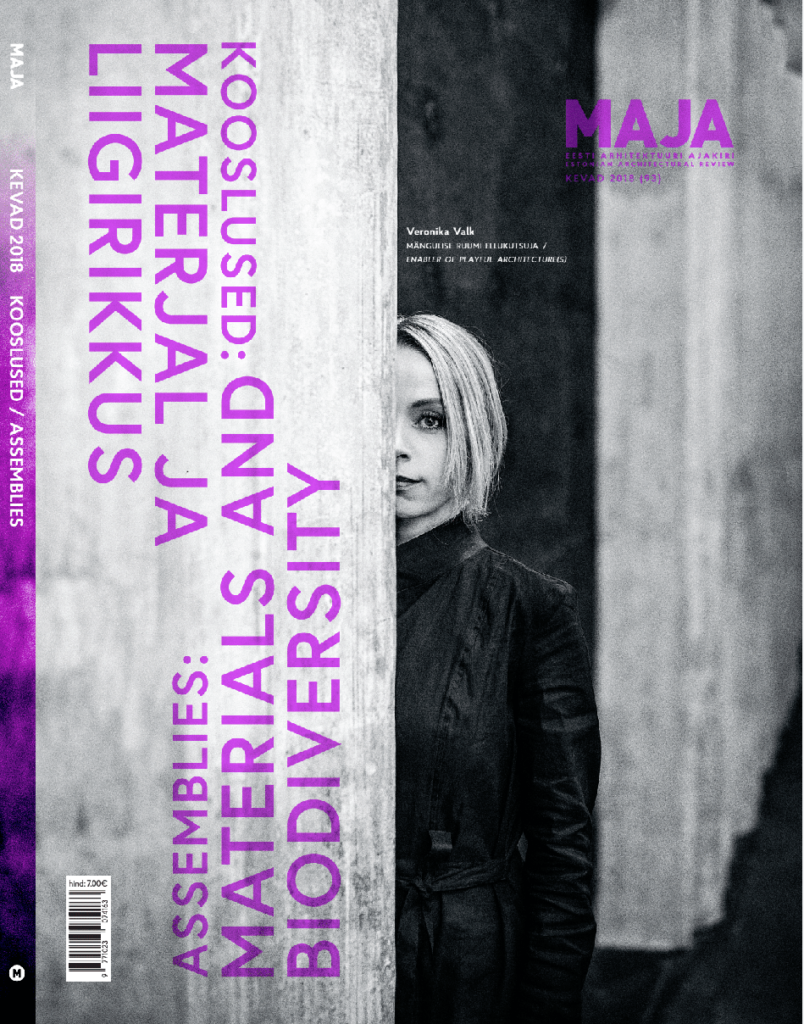

Veronika Valk. Enabling Playful Architecture 〉 Interviewed by Hans Ibelings

URBAN NATURE AND BIODIVERSITY

Urban Observations: Fenced garden City 〉 Eve Kiiler

Urban Nature — For Whom and Why? 〉 Aveliina Helm

Urban biotope landscapes 〉 Johan Paju

Biodiversity at stake 〉 Madli Linder

Urban gardening and nature through the eyes of a landscape architect 〉 Rea Sepping

Photos from series “Shanghai, the last plane” portray gardens in Hiinalinn, Tartu. Maria Kilk, 2017

MATERIALS, BIOLOGICAL COMMUNITIES AND BIODIVERSITY — MATERIAL CONSCIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE

‘Brunelleschi was the Elon Musk of his time,’ writes Jelle Feringa, an architectural robotics entrepreneur. Why is there so little innovation to be found in architecture and why is it usually limited to experiments in university labs? Considering that the primary purpose of architecture is to offer protection and shelter, do we need innovation in materials and technology so urgently after all? Although this core function of buildings, to provide protection and shelter, may seem perpetual and immutable, the ways how it has been accomplished have still changed over time. The problems we face every day, although they may often appear timeless or universal, inevitably reflect the times we live in. The construction sector today accounts for the largest share in carbon dioxide emissions and energy consumption in many countries. By innovating the construction sector, we can also improve the fortunes of our environment.

Professor of architecture Rachel Armstrong, civil engineer Manja van de Worp and entrepreneur Jelle Feringa will speak about the horizon of architectural innovation with a focus on materials and production. Armstrong, who visited the biology-themed Tallinn Architecture Biennale, takes special interest in the opportunities offered by protocell technology. Synthetic adaptive protocells are sensitive to their environment and can be used in building materials. Engineer Karl-Eerik Unt writes about the role of materials in architecture and asks what stops architecture from taking the helm in material innovation. We also provide an overview of some of the more recent Estonian Timber and Concrete Buildings of the Year. Art historian Darja Andrejeva shows us around in the renovated Luther’s Machinery Hall, which can be regarded as an outstanding example of the use of reinforced concrete in early 20th century civil engineering.

Digital modelling tools and computer-controlled machine tools offer opportunities for the creation of novel forms and special solutions whose price tag still remains in the same range with standard solutions. Sille Pihlak, PhD student at the Estonian Academy of Arts, writes about the cooperation platform of Estonian log house manufacturers, civil engineers and architects that adds value to local timber. Architect Kaiko Kivi tells us of his work where he combines algorithmic design and robotic machine tools to create such solutions whose manual realisation would be inconceivable. We have not created anything new when a milling robot cuts out a medieval sculpture, says architect Gilles Retsin, and looks for a discreet, easy-to-manufacture material that would correspond to discreet digital logic and would be suitable for use in residential buildings.

In different times, the application of the principles of biology in architecture and spatial planning has either focused on metaphors or on the logic of how things function. The approach named after the Rebuild by Design project carried out in New York in the wake of the climate crisis focuses spatial planning on the sustainability of cities. But how are things in Estonia? The natural biological communities in Estonian cities have retained their relative species-richness only here and there. Maybe the first thing that we should do is to pay more attention to our urban biological communities and investigate what can be done for their preservation and increased biodiversity. Do we really know how much they contribute to our living environment? Botanist Aveliina Helm writes about the benefits of urban biodiversity from the perspectives of nature conservation and health of city dwellers. A roof landscape, which combines a place of recreation with plant communities characteristic of local nature, thereby offering an experience of freely developing urban nature, has been prepared under the guidance of Johan Paju, a landscape architect of Estonian origin who works in Sweden. Landscape architect Rea Sepping writes about the unique and resilient urban gardening culture of Tartu. Her article is illustrated with Maria Kilk’s photos of the hidden culture of the gardens in Hiinalinn, Tartu.

The person of the issue is architect Veronika Valk-Siska whose work across a range of architecture-related fields is driven by her desire to be involved in different stages of spatial planning and design and to initiate architecture-related processes on different levels, thus arriving at a unique combination of aspects in her work.

Although the two topics of this issue of MAJA – materials and biodiversity of urban nature – may seem to have little in common, the articles in the issue are characterised by a way of thinking that connects different scales, an astute perception of completeness and a precise vision of how to make a conscious contribution to the system. These stories are about responsibility.

Kaja Pae, Editor-in-chief

May, 2018