The cultural shift towards using materials and energy that are contained within planetary boundaries requires a reconsideration of the most fundamental assumptions about how buildings interact with the world.

Designing with a territory values connection over extraction. Clara Kernreuter from Atelier LUMA and Maria Helena Luiga from kuidas.works discuss bioregional design.

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS

If we could overcome the paradox of meat and make the hidden realities of the animal industry even slightly more visible, it is conceivable that we might begin inching towards dietary practices that do not require the exploitation of animals.

Although dictionaries define the term ‘plateau’ as a stable, fluctuation-free state, they also include a caveat: it only lasts for a certain period of time. So, what comes next?

Vertikal Nydalen, a mixed-use building in Oslo designed by Snøhetta, pushes the boundaries of a modern natural ventilation system, writes Ott Alver.

In the UK, a number of councils have adopted the passive house method in order to realise their growing ambitions in the housing sector. Could this also lead to an increase in spatial quality?

Authors traced the bigger processes that are connected to the production of engineered wood - these materials are produced from industry leftovers, but also from trees that are cut for that purpose only.

In addition to being home to trees, cities or urban environments are also home to 70% of the Estonian population—are these people not entitled to clean air as a human right?

Hence the main question of this article: what power does stench have? And who gets to feel the stench? Who talks about the stench? Who gets to decide where it stinks?

No more posts

Editors' choice

What kind of relationship between a space and its surroundings would help to avoid the objectification of space—i.e., treating buildings or areas as sculptures or fully controllable objects?

Paide State Secondary School is an excellent example of the mutually complementary dialogue between a historical space and contemporary architecture.

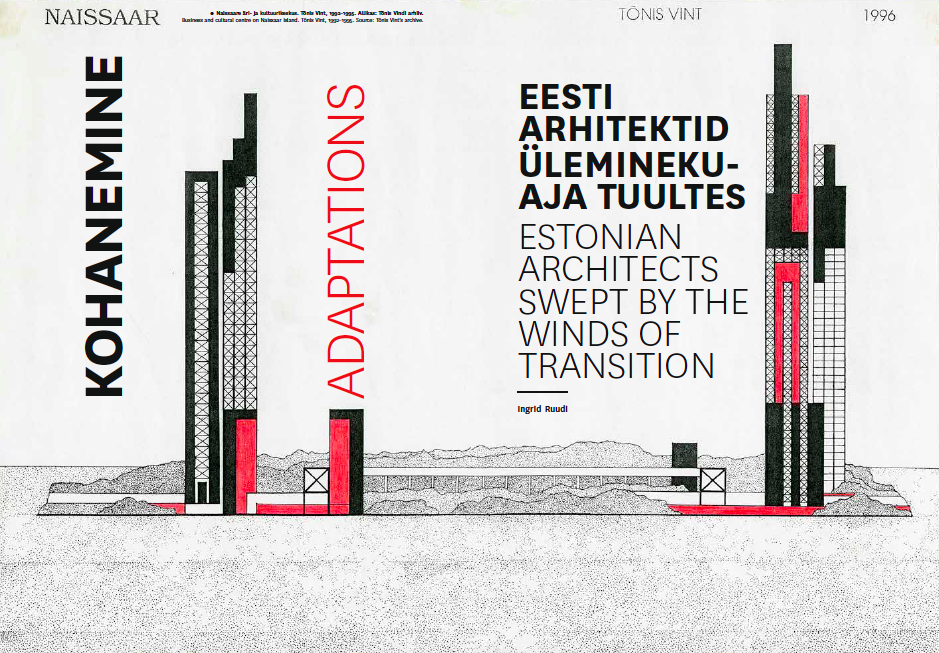

Little was built following the re-establishment of Estonian independence in the early 1990s, however, the debates held and practices established largely came to set the foundations for the dominant issues in the architectural field in the past decades.

What kind of relationship between a space and its surroundings would help to avoid the objectification of space—i.e., treating buildings or areas as sculptures or fully controllable objects?

No more posts

Most read

Tänasel kujul on Kultuurikatel aga otsekui pommitabamuse saanud. Protsessi käigus on sealt minema pühitud nii ideed kui ka autorid ja valminud hoonest on kärbitud viimanegi avalikku kasutust toetav arhitektuurne struktuurielement. Kultuurikatlast on saanud keerulise logistika ja põhjendamatu ruumiprogrammiga elitaarne A klassi rendipind, mille on kinni maksnud Euroopa ja Tallinna inimesed.

How does change in society reflect in architecture? In order to answer this question, we look back on the spatial design in the thirty years of regained independence. What kinds of spaces have accommodated us in the last three decades at work, in school and while enjoying culture? What have our homes been like?

Toomas Paaver admits that solving some problems of spatial planning may indeed seem impossible, however, the self-same impossibility has always intrigued him. His way of thinking is marked by spatial structuredness and ability to find causality in complex connections providing his perception and argumentation with a particular grasp. Would it be possible to work with such a versatile topic as a functioning common space in any other way?

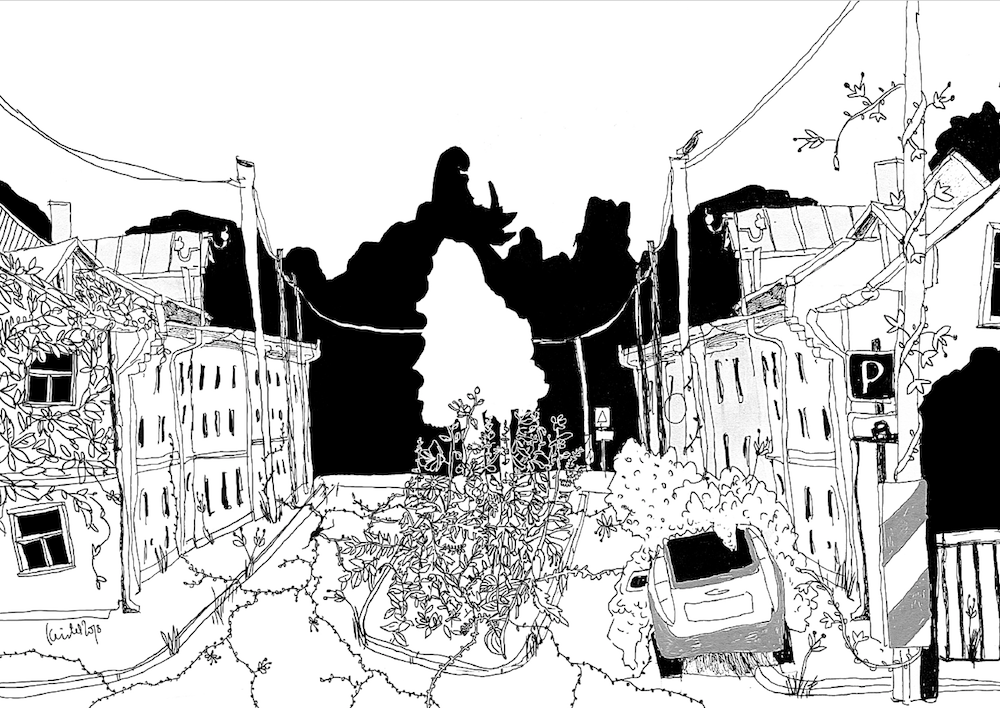

The order of nature is complex, interesting and beautiful. However, mankind’s understanding of order and beauty tends to be somewhat primitive and thus we are increasingly losing the sense of balance that could direct our activities. Green areas are meant for public use, but in reality they have become neatly mowed lawns that people never walk on and that we have consequently made unsuitable for other living organisms.

Every act of redesign, renaming or shift, especially in downtown, always bears reference to choices and decisions with a broader ideological background.

Maxime Cunin of Superworld writes about designing infrastructure of and for sharing.

Case Study - apartment building in Paris, at 62 Rue Oberkampf, architecture by Barrault Pressacco.

Jenni Partanen, the Future City Professor at TalTech, discusses the challenges in planning a smart city and introduces her research plans, using Ülemiste City in Tallinn as an example.

No more posts

Tänasel kujul on Kultuurikatel aga otsekui pommitabamuse saanud. Protsessi käigus on sealt minema pühitud nii ideed kui ka autorid ja valminud hoonest on kärbitud viimanegi avalikku kasutust toetav arhitektuurne struktuurielement. Kultuurikatlast on saanud keerulise logistika ja põhjendamatu ruumiprogrammiga elitaarne A klassi rendipind, mille on kinni maksnud Euroopa ja Tallinna inimesed.

No more posts