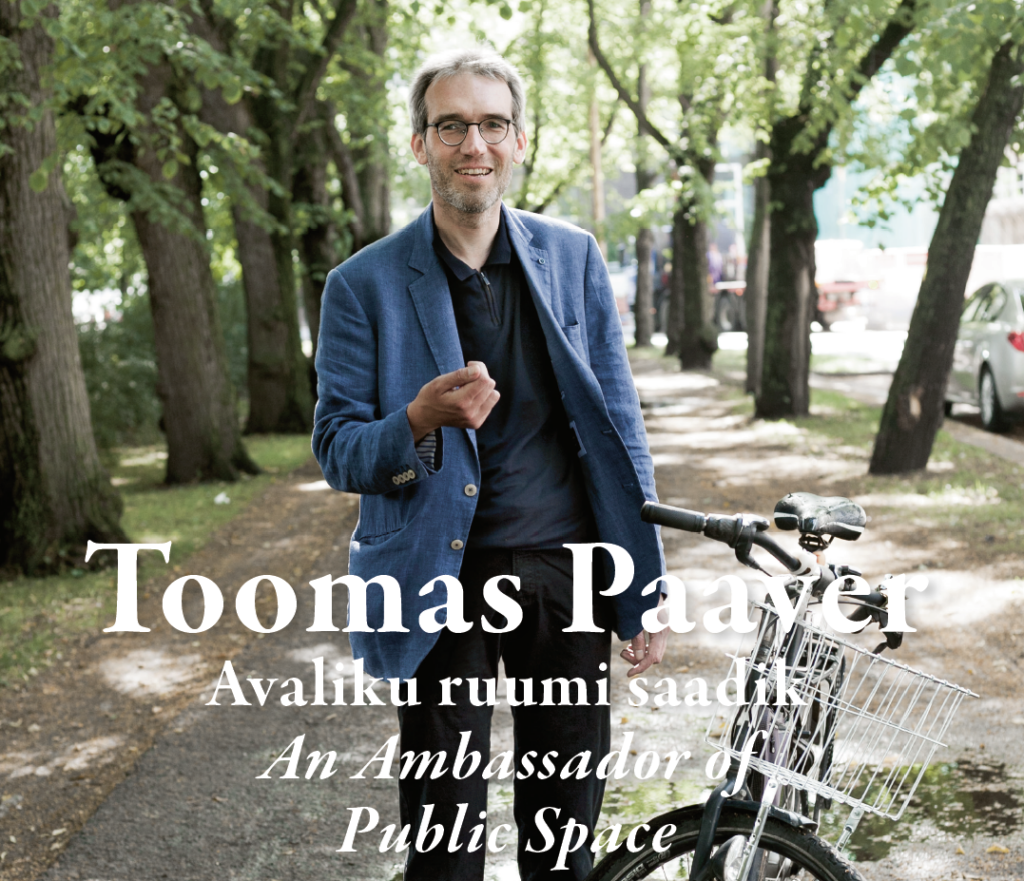

Toomas Paaver admits that solving some problems of spatial planning may indeed seem impossible, however, the self-same impossibility has always intrigued him. His way of thinking is marked by spatial structuredness and ability to find causality in complex connections providing his perception and argumentation with a particular grasp. Would it be possible to work with such a versatile topic as a functioning common space in any other way?

The genesis of Kalarand is a search for novel urban ideals. Amidst arduous planning and controversy, a number of urban activists matured and professionalised. In a prototyping-like process, several expectations we consider fundamental today on the subject matter of public space and spatial justice were made visible, and solidified. Johanna Holvandus writes on the changes in urban activism and urban processes.

The Urban Forum held on June 14th–15th was looking for the subtle balance between the activities of visitors and locals as well as the old and the innovative new.

All pioneering and innovative projects need support to prevent them from getting stuck in the old rut under the pressure of red tape.

Living close to water is good for our health: it reduces the risk of premature death, obesity, and has a generally restorative effect on people’s mental and physical health. 1 In the city, water is often so near, yet so far. Did you know there are more canals in Birmingham than there are in Venice, but people have been separated from the water by bad urban space? Tallinn has a long coastline but there are very few places in the centre where you can access the sea at all.

Spatial design of a city is not a project with a clear beginning and end, but a continuous process, and a wickedly slow one at that.

What kinds of forces bear upon the process of creating a new urban area today? What urban development questions do we already have a grip on? What issues are we still grappling with and how? Indrek Allmann recounts the journey toward climate-neutral Paljassaare.

In the last few years, several public buildings with unexpected combinations of functions have been built in Estonia due to practical reasons, and soon, a series of state houses combining a kaleidoscopic array of institutions in smaller towns will follow. How do these public buildings reflect our present times, and how should they?

After the slow-burning and partly contestable success stories of Rotermann Quarter and Telliskivi Creative City, the eyes of Tallinners interested in urban design or just longing for a better urban space turned to Noblessner—the privately developed waterfront set to become one of the first chapters on the road to open the coastal areas of Tallinn to its citizens. Though far from complete, the lively quarter already offers a chance for a status report and an insight into the entrenchment of certain spatio-social tendencies in the Estonian real estate landscape.

Andres Sevtsuk is a Professor of Urban Science and Planning at the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, where he also leads the City Form Lab. Maroš Krivý is a professor of Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts.They shared their insights on current state and challenges of Estonian architecture.

No more posts

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS