SPATIAL DESIGN

It is no news to architects and real estate developers that the design of a new spatial environment usually begins with parking spaces as if it was the fundamental value. More and more practitioners, however, complain about the outdated mindset related to parking norms and the need for a new approach allowing to implement more sustainable decisions. Tartu city architect and the head of the spatial design department Tõnis Arjus discusses the city’s new ambitious online app considering the parking spaces according to the actual need.

Contradictions of spatial planning are caused by the time required to process comprehensive and detailed plans as well as (spatial) gap between the two. How to better make sense of planning processes and to alleviate rigidity of the aforementioned?

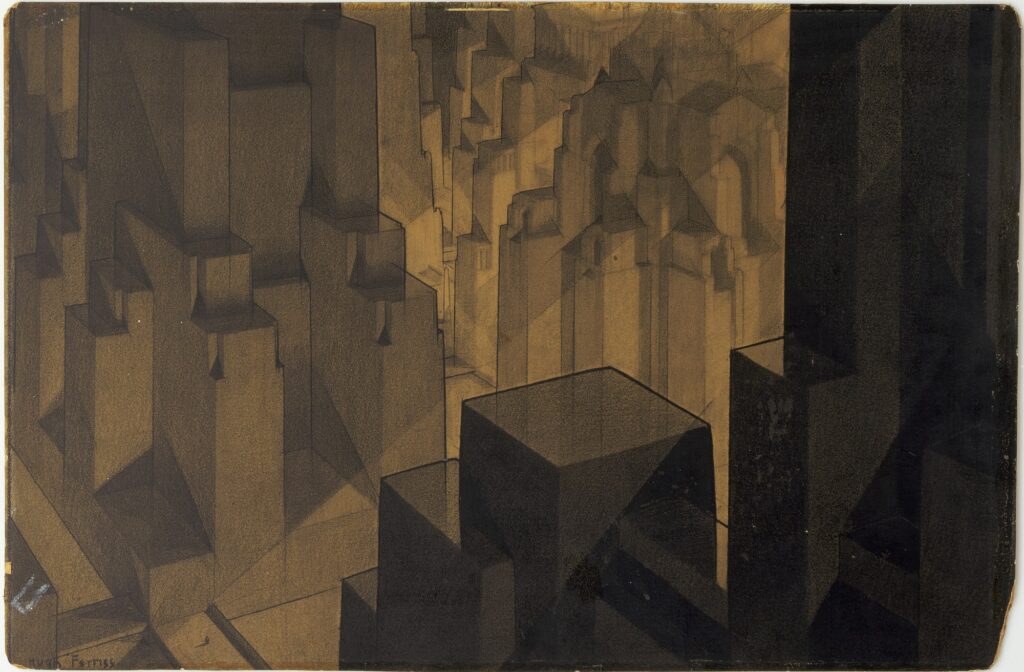

If there is any feeling of blandness, or risk aversion, or scant sense of place, it is not due to insufficient bike lanes or pedestrian squares, but rather because the larger questions of what is produced and who gets to have how much have already been decided.

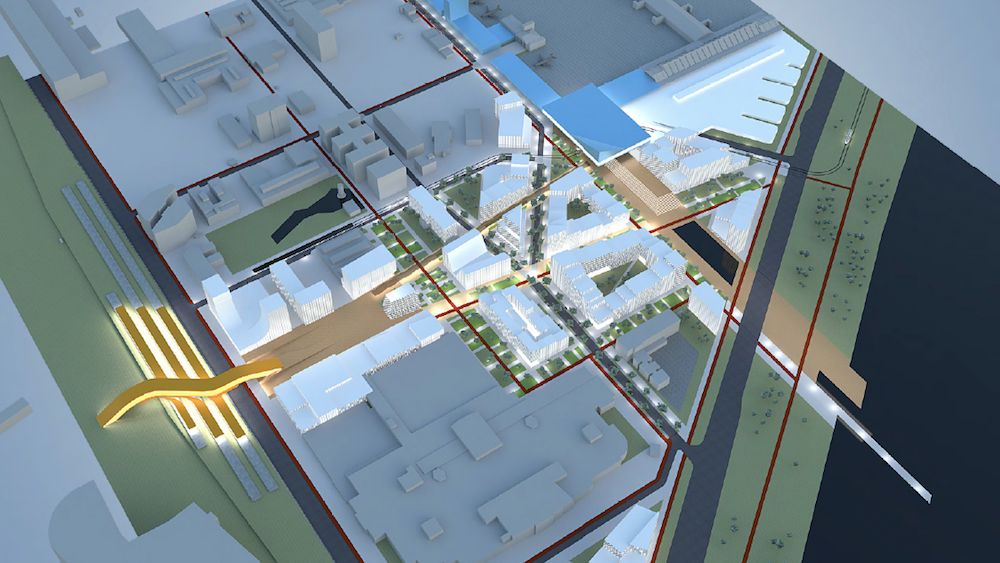

The general plan for the Põhja-Tallinn city district is headed in the overall direction of diminishing the proportion of industry, increasing openness to the sea, developing the mobility environment via public transportation and bicycle traffic, and strengthening the blue-green network of the district.

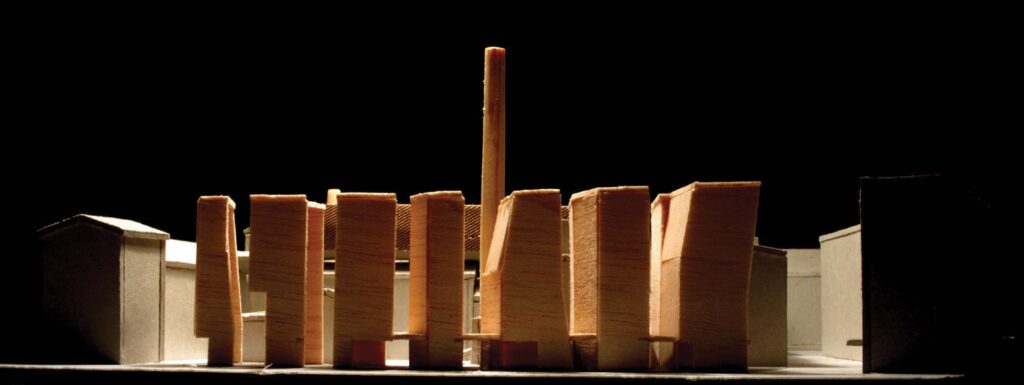

Rotermann Quarter stands out for the diversity of its new-builds and reconstructed former industrial buildings. There is probably no other area in Estonia awarded with as many prizes as this one. Mathilda Viigimäe and Kristi Tšernilovksi shed light on the architectural development of Rotermann Quarter.

We are asking how the European Union, local government and the architectural office can contribute to the development of architectural thought?

What kinds of forces bear upon the process of creating a new urban area today? What urban development questions do we already have a grip on? What issues are we still grappling with and how? Indrek Allmann recounts the journey toward climate-neutral Paljassaare.

A building with a strong character is easy to hate. Or to love. Take, for example, Tallinn City Hall—few are indifferent to it. Many see the City Hall as an ingenious artificial landscape and urban stage, while others consider it a relict of the Soviet occupation that is unfit for a free Estonia, just like the Sakala Centre that was demolished in 2007. There are many other lesser or better known buildings from the Soviet period that are architecturally ambitious, but unacceptable to many for aesthetic or ideological reasons.

In the last few years, several public buildings with unexpected combinations of functions have been built in Estonia due to practical reasons, and soon, a series of state houses combining a kaleidoscopic array of institutions in smaller towns will follow. How do these public buildings reflect our present times, and how should they?

Over the course of the past thirty years, designing school spaces has migrated from being a marginally positioned subject matter to the centre of focus in the field of architecture, supported by scientific studies and continual research and development. The spaces for learning have acquired a new image and meaning.

Postitused otsas

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS