Where is the line between genuine development and pointless construction? How to use concrete reasonably rather than wastefully? In what form should concrete figure in contemporary architecture?

In 2016, a group of women moved into a building in the borough of Barnet on the outskirts of London—a building that had been developed and built in collaboration with them and specially for them. Thus culminated a process that had begun in 1998, when some of these women founded the Older Women’s Co-Housing (OWCH) group.

The aging population requires nothing less than a radical retooling of the territory, with architects and urban planners at the forefront of this transformation.

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS

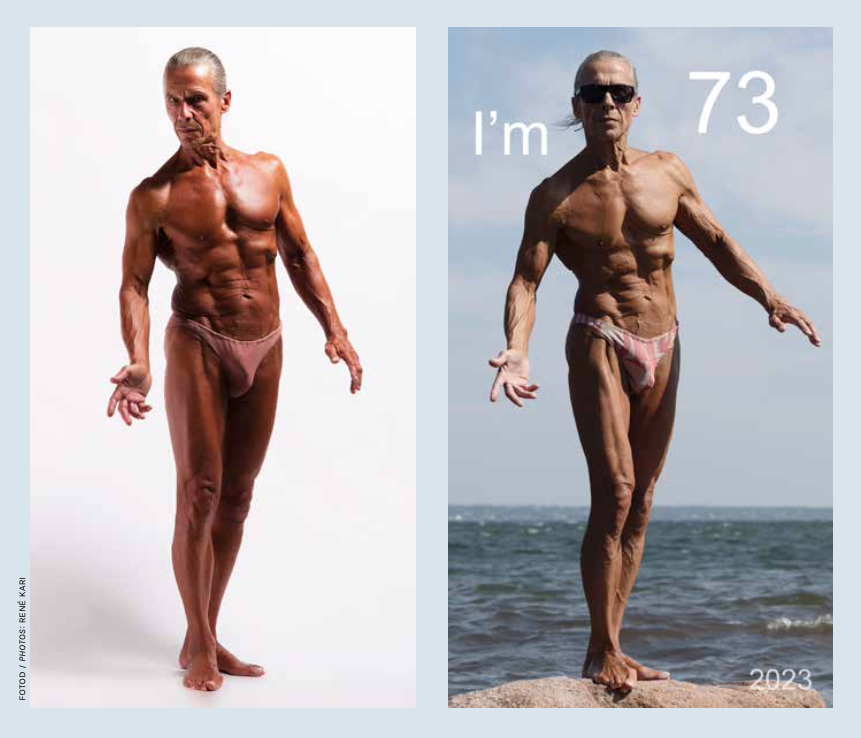

How should we understand age? Or old age? In some cases, it is perceived as a value—something good, like in wines that improve over time. Old cities and old works of architecture likewise comprise a number of values that new-made ones can lack, and even in people, it is generally taken to be a positive thing that they become wiser, more mature, and more experienced with age.

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, collectively known as the Baltics, are three small countries that most of the world finds pretty much indistinguishable. As a geopolitical term, ‘the Baltics’ took root only in the 20th century. The more distant past and cultural history of the three countries differ on several levels.

Perhaps it is namely in defiance against externally imposed homogenising simplifications that we tend to turn to more distant places for inspiration and view local trends and tendencies as something confined only to national borders. However, anxious times encourage unity, urging us to discover and interpret our identities ourselves instead of letting others define us. In order to be carried and consolidated not only by fear, but also joy, pleasure, and curiosity we invite to discover commonalities and peculiarities of the Baltic countries!

Wide breadth, blurred boundaries, ambiguous endings and beginnings—the charm of the Baltic condition is not easy to grasp. But as Latvians say, per Reinis Salins: ‘Katram savs stūrītis’ (‘Everyone has their own corner’).

Architect Johan Tali, landscape architect Merle Karro-Kalberg, architect Siiri Vallner, project manager Priit Õunpuu and interior architect Hanna Karits discuss their experiences of using limestone in recent projects.

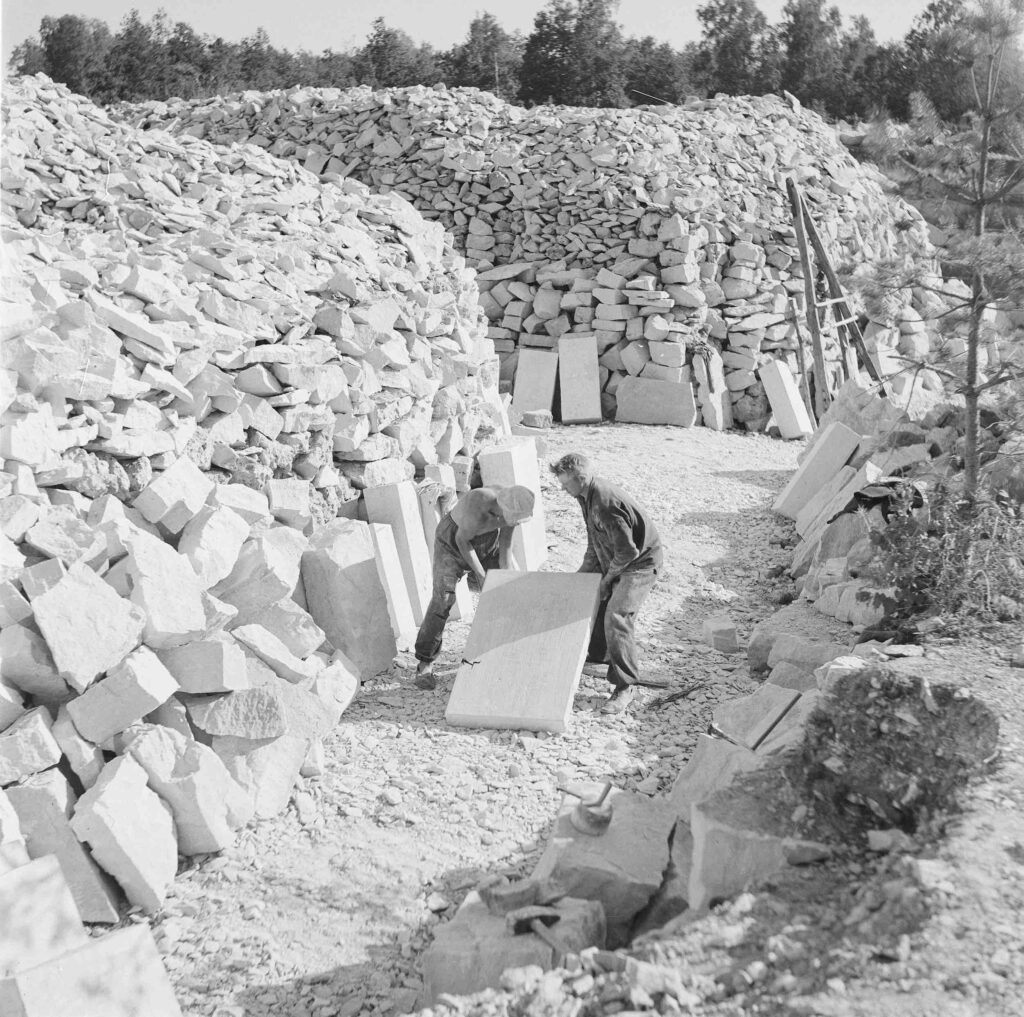

Limestone in Estonian Construction and Architecture in the 20th Century.

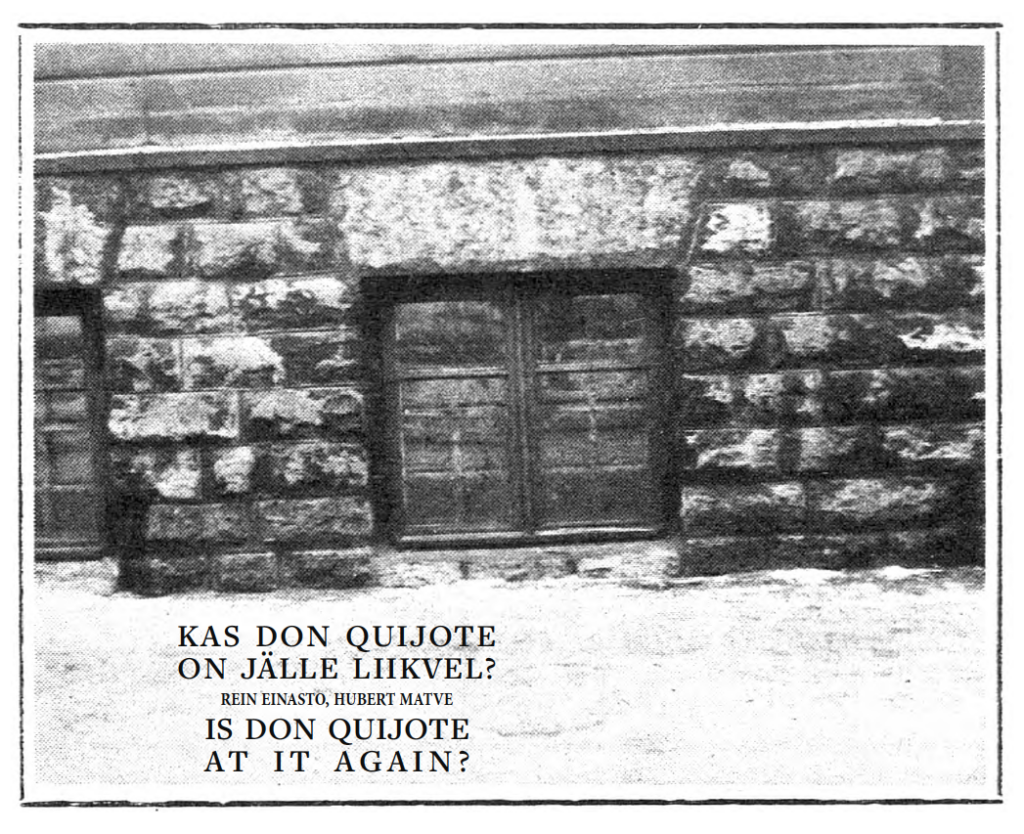

This piece by geologist Rein Einasto and engineer Hubert Matve was first published in newspaper Sirp ja Vasar on the 13th of July, 1987. Forty years later, Rein Einasto maintains that sustainable and multifaceted use of local stone is a necessity without an alternative, and a wide open road of possibilities.

Case Study - 4 social housing units with 68 apartments in Switzerland, architecture Gilles Perraudin and Atelier Archiplein.

Case Study - apartment building in Paris, at 62 Rue Oberkampf, architecture by Barrault Pressacco.

Case Study - office and apartment building in London, 15 Clerkenwell Close, architecture by Groupwork.

Acting as material broker, Amaya Hernandez writes about saving more than 100 million years old stone from being ground into aggregate for a concrete planter.

No more posts

Editors' choice

Paide State Secondary School is an excellent example of the mutually complementary dialogue between a historical space and contemporary architecture.

No more posts

Most read

Material use which takes advantage of its specific properties lessens the chance of later unwanted changes in the original architectural design and guides the user experience. What stops architecture from taking the helm in material innovation?

The interview is based on Yael Reisner’s lecture Why Beauty Matters in Architecture; the cultural bias, the enigma, and the Timely pursuit of New Beauties given at the Estonian Academy of Arts in February 2018. She was also chosen to be the head curator of Tallinn Architecture biennale in 2019 with her chosen title Beauty Matters, The Resurgence of (the temporarily dormant) Beauty.

In the last five years, one hot topic for experts in the field of green transition, which has been cropping up at international conferences as well as on the desks of pertinent officials, is the handling of spatial heritage.

A rooftop landscape in Stockholm is a case study to create natural biotope in urban public space for people to use it and gain a year-round experience of the city's nature.

Thinking of design as a service means bringing into focus the user and user needs. The impact of user-specificity is steadily increasing in how the processes of spatial design are approached. Ave Habakuk from the Living Street movement writes about how to think of the street as a service.

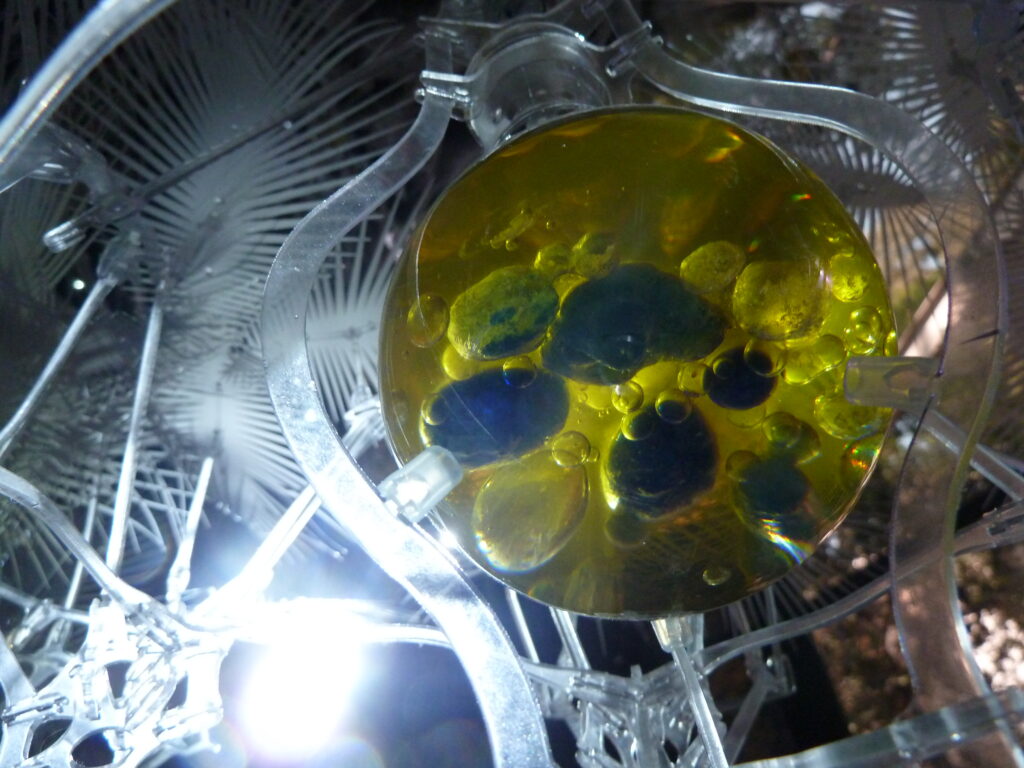

There is an ongoing discussion how to reach novelty in architecture with computation-driven tools, combining material knowledge with fabrication possibilities. In an attempt to seek for the new spatial qualities emerging and deepening the collaboration between the stakeholders of construction, we discuss it with experimental architect Rachel Armstrong, fiery engineer Manja van de Worp and innovating fabricator Jelle Feringa.

Maja's summer edition soon available!

Estonian mobility entrepreneurs are on their way to the top. Kaja Pae asked Estonia’s flagship mobility entrepreneurs about their innovative practices and how they portray the future of mobility.

No more posts

There are tumultuous times in the seafront development in Tallinn with variously motivated changes. This is the moment when architectural institutions must perceive their sense of responsibility and contribute to the big picture with their expert knowledge.

No more posts