Authors ask: how to talk about a railway that currently exists only in our imagination, but is nonetheless very present in our daily lives?

Infrastructure qua base structure underlies or serves the superstructure. Superstructure must take into account the load-bearing capacity of the base and must not exceed it. The variety of connections and dependencies gives rise to sustainable and resilient bio- diversity, whereas simplifying it makes life vulnerable.

In contemporary discourse, the term 'infrastructure' typically conjures images of roads, bridges, and utilities—physical systems essential to the functioning of our societies. However, the concept of infrastructure can be extended beyond its tangible form to encompass networks of care, healing, and empathy. As a community initiative, an ‘infrastructure of care’ transcends mere functionality, weaving connections that nurture the human spirit and foster collective healing.

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS

All new hard infrastructure should be engineered to double as social infrastructure, writes Mattias Malk.

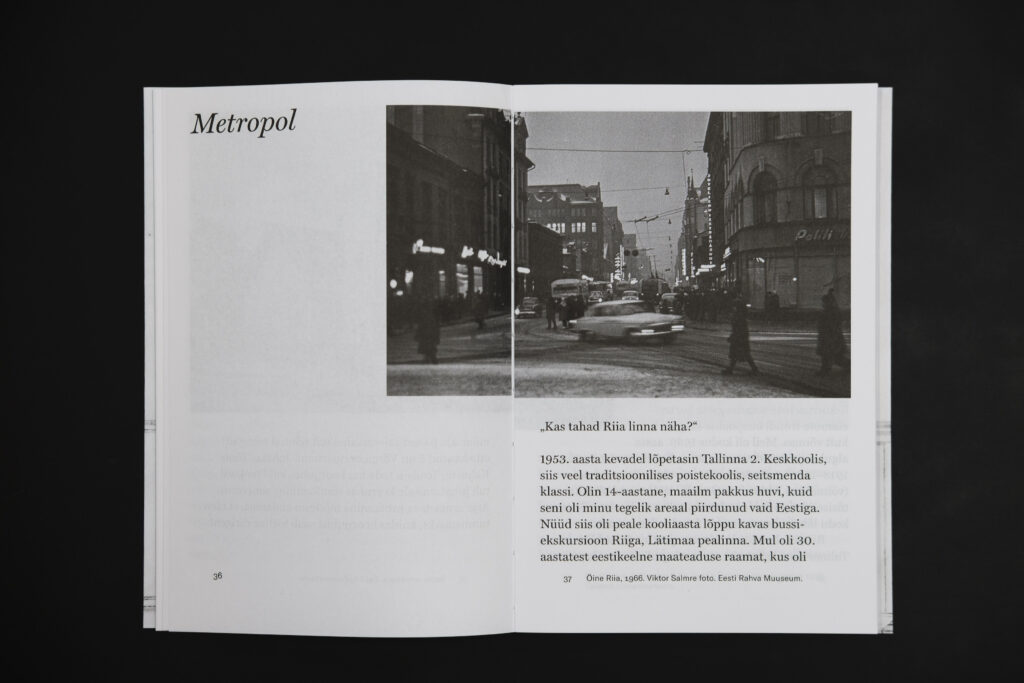

Ingrid Ruudi discusses architects’ relationship with time and the various ways in which architects in their later years record their doings as history.

When a certain building technology or material is sidelined for an extended period, one is bound to get the impression that it is intrinsically obsolete. This has happened with natural stone, which architects, when asked about its potential for use, describe only as being too expensive, too labour-intensive, incompatible with the public procurement system and, as can be witnessed in renovation projects, simply too complicated to build with. The inability to imagine a future different from the present is typical to the 21st century, and hence, the main use of limestone in Estonia remains blasting it into rubble that can be utilised as landfill and concrete aggregate.

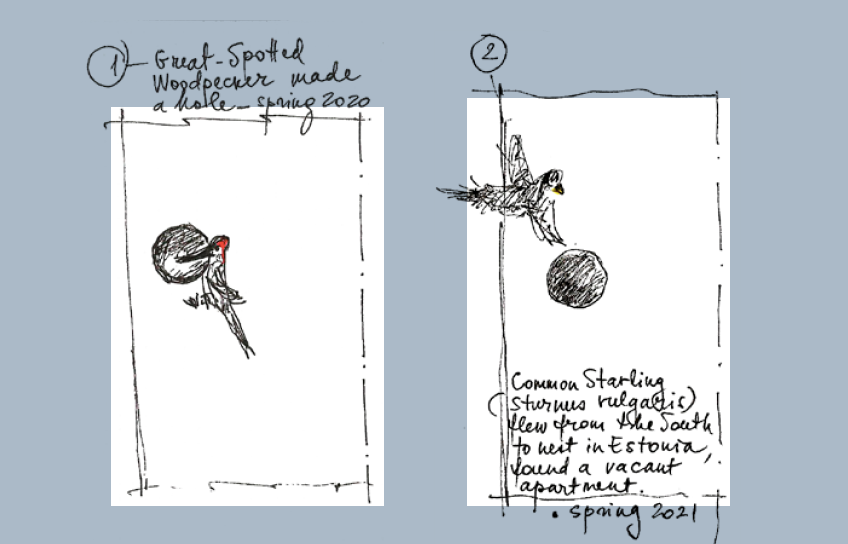

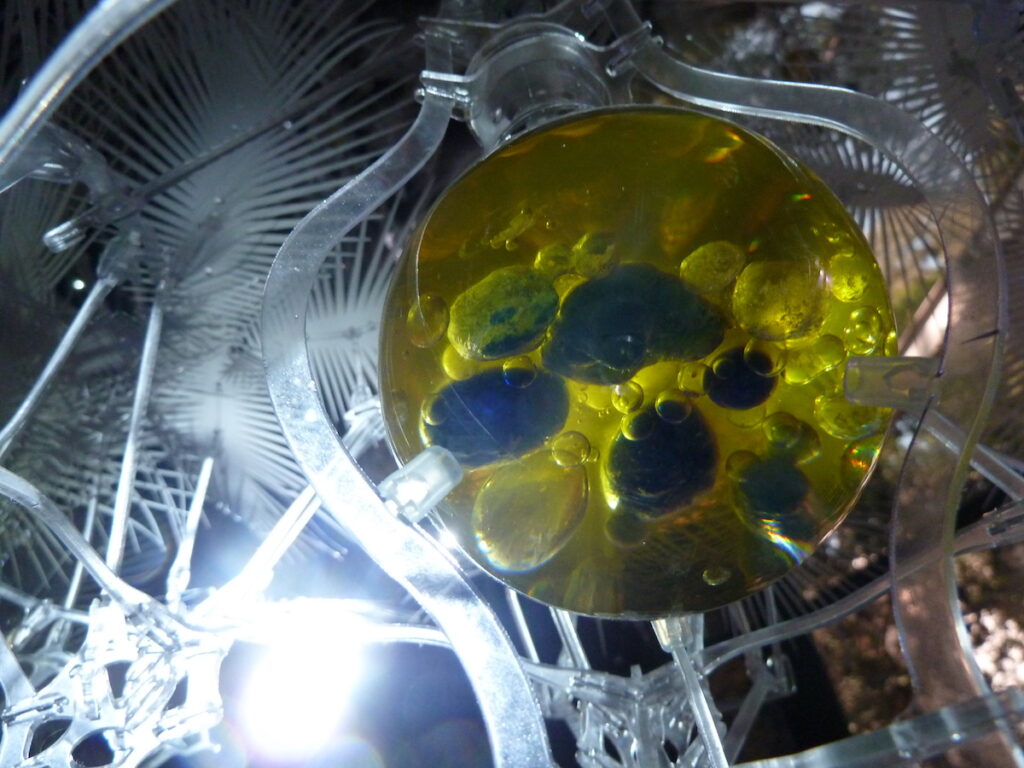

What is happening in the freshly insulated walls of author's home?

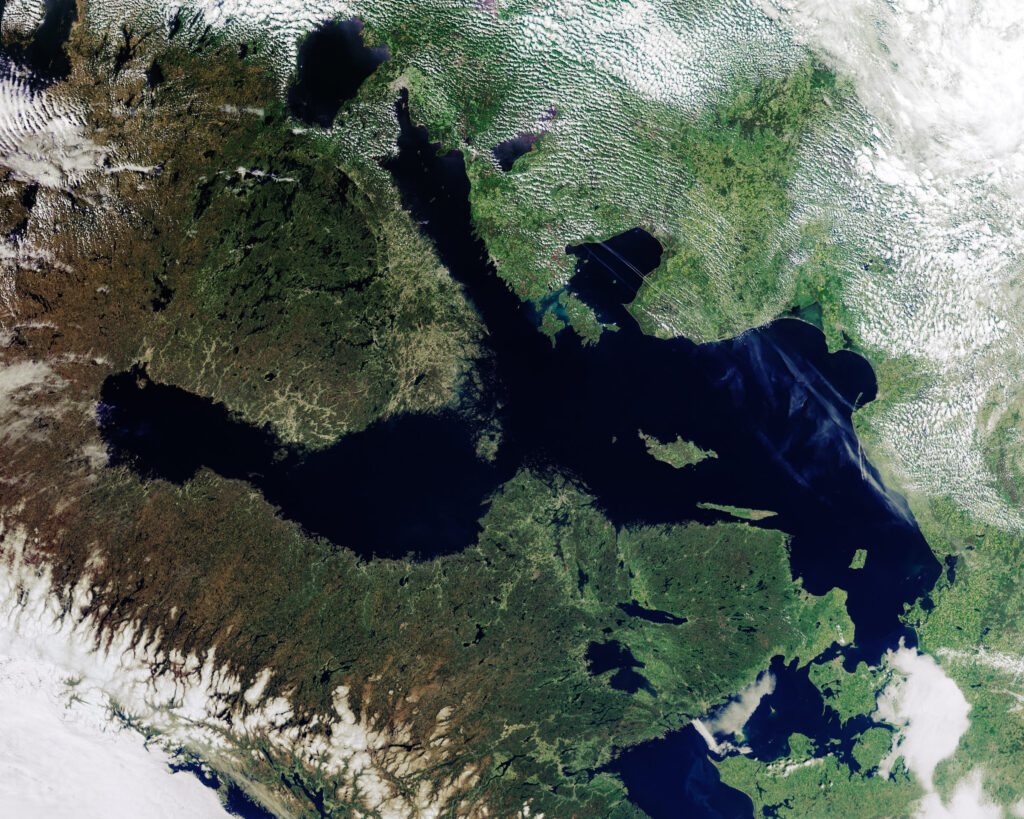

One of the ways to alleviate environmental problems might lie in architecture that brings people closer to their environment again. Estonia as a maritime nation has plenty of opportunities for this.

n Kärdla School in Hiiumaa, designed by Arhitekt Must, outdoor recess is not some laborious ideological effort, but simply an ordinary and natural idea, writes Kadri Klementi.

Mihkel Tüür writes about the wooden slat house that he built on the island of Muhu fifteen years ago.

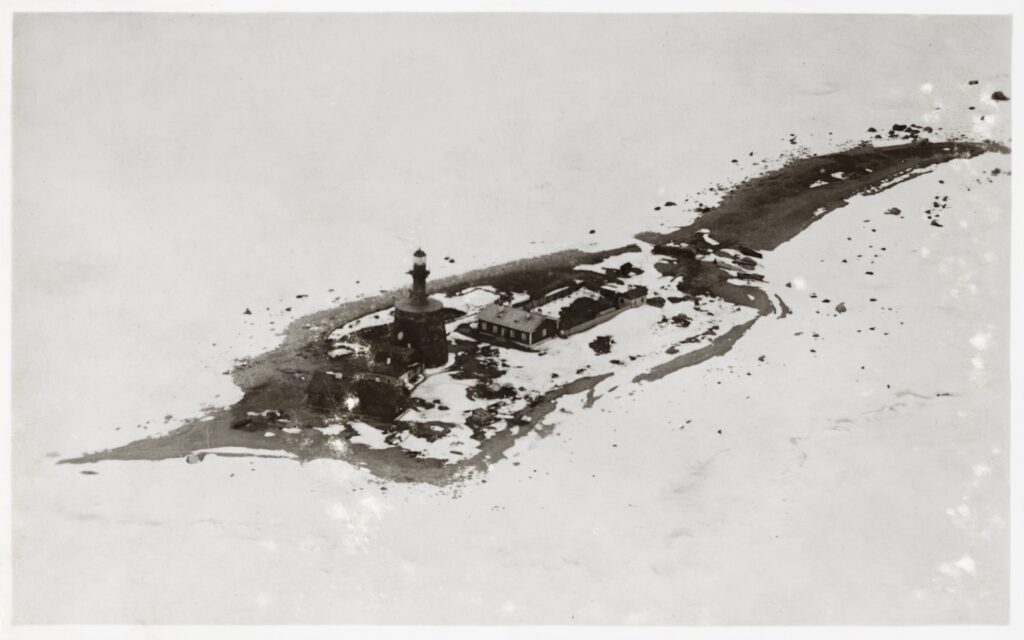

I believe that many a reader will imagine islands in the form of a curled-up coastline—after all, often there is little else there besides sea foam and bird screeching. Although Estonian islands are slowly growing in size, we still have a very large number of small islands—reefs, rocks, islets—whereas not so many islands where people would live all year round.

Hiiumaa municipality architect Kaire Nõmm takes a look at what life could be like on one of Estonia’s main islands.

No more posts

Editors' choice

Most read

Norway is a country characterised by high voluntary activity, 78% of its 5.4 million inhabitants are members of at least one voluntary organisation, 48% are members of two or more. Volunteering is and has been an important aspect of Norwegian society, and in recognition of that, 2022 has been designated as the Year of Volunteering.1 During this year NGOs and smaller volunteering associations together with local, regional, and national governments have collaborated in highlighting the value of volunteering in Norway.

Life-centric approach in architecture and spatial planning may pave the way for more symbiotic relations between nature and the city.

Peatoimetaja Kaja Pae.

Rannamõisa funeral home has taken a highly interesting path since its opening. Namely, the opening of the building was accompanied by a change of identity. Was the change of identity brought about by the author through the architecture or the client through the functions of the building? What does this say about our culture of death and the development of the respective architecture?

A Research Study on Urban Planning in Tallinn at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts

The Estonian National Museum’s own home was completed thanks to three very simple underpinnings: belief, trust and cooperation.

The new terminal is not just a building, it is above all an urban act, showing the way to and perhaps even anticipating the integration of the harbour and the entire seafront area.

Thinking through stone opens up a fresh perspective on construction culture (and the lack thereof), availability of local building materials and their untapped (economic) potential, and, ultimately, on building truly long-lasting buildings.

In Tallinn, we have had quite a lot of good visions for the future: development plans, studies, and strategies. Yet, we have not acted according to these ideas which has resulted in a different environment than envisioned—especially if we look at our mobility and the quality of public spaces. Our colleagues in Vilnius have created a simple street manual and it seems that they are successful at implementing it. We gathered Jonas and Anton from Vilnius to find out how they have done it.

No more posts