We have gained an unprecedented amount of trust from our employers. Work has suddenly become dispersed, taking place asynchronously at different locations and different times. One gets a sense now of deeper reflection on how companies should organise their work and inspire their workers. This has led to a shift in understanding—what takes place within the environment has begun to affect the environment itself and its fundamental idea, which in turn guides the aesthetic decisions on space.

How does change in society reflect in architecture? In order to answer this question, we look back on the spatial design in the thirty years of regained independence. What kinds of spaces have accommodated us in the last three decades at work, in school and while enjoying culture? What have our homes been like?

What is the image conjured up by the phrase ‘the industrial heritage of Tallinn’? Is it the Creative Hub (Kultuurikatel), Rotermann Quarter or perhaps Noblessner Foundry (Valukoda)? Henry Kuningas resorts to outstanding examples to describe the main features implemented in the reconstruction of the industrial heritage in the past two decades.

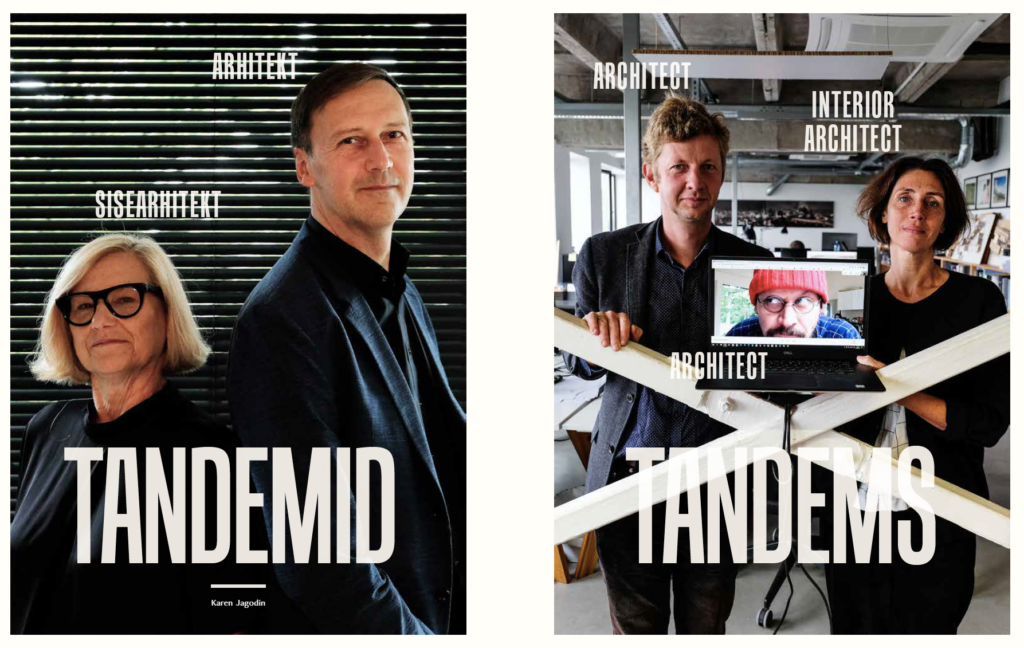

For the current article, I spoke with two architect and interior architect tandems whose cooperation has become their preferred form of creative effort: Kalle Vellevoog and Tiiu Truus as well as Mihkel Tüür, Ott Kadarik and Kadri Tamme.

How can human well-being and cognitive processes benefit from evidence-based design? We discuss it on the example of teaching and research facility in the Delta Centre of Tartu University and the creative house Vita of Tallinn University.

Andres Sevtsuk is a Professor of Urban Science and Planning at the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, where he also leads the City Form Lab. Maroš Krivý is a professor of Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts.They shared their insights on current state and challenges of Estonian architecture.

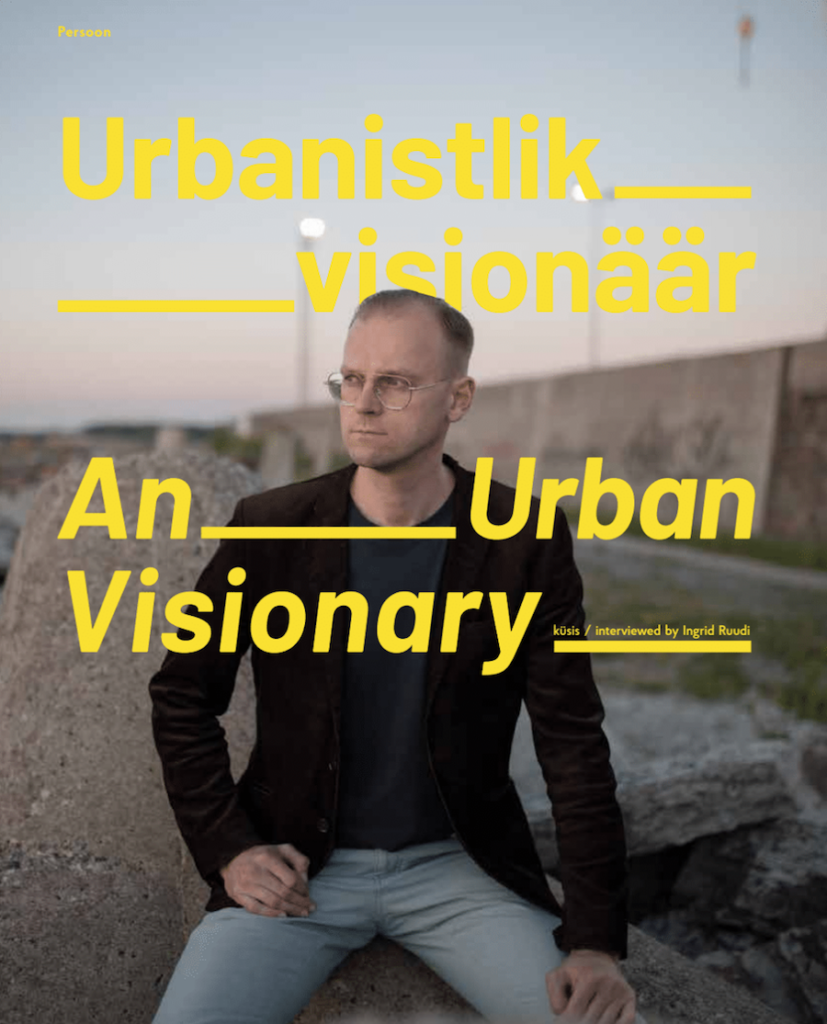

Villem Tomiste is like a figure from the beginning of 20th century Young Estonia movement – genuinely European, deeply urban, and as such, slightly suspicious for the local conservative community. Unlike many architects who preach social benefits, he actually lives by what he promotes in his civic visions – urbanistically to the core, commuting on foot and by tram, avoiding over-consumption, and with a refined aesthetic sensibility. Contemporary spatial culture is, for him, a field of opportunities: extending from urban planning and landscaping projects to dialogues with contemporary music, the visual arts and various exhibition practices.

To what extent does the administrative reform correspond to long-term settlement changes and the National Spatial Plan Estonia 2030+?

European Union assistance has had a very strong influence on the appearance of Estonian towns, villages and landscapes in the last decade. Much has been done, but the real question is what has been done, and how. At the start of the previous European assistance period, local governments were encouraged to be active in asking for support. Something akin to a mentality became widespread: if money is being handed out, it has to be accepted and spent.