For Veronika Valk-Siska, architecture neither begins nor ends with a design or a building. Her career in architecture until now can be read as a reflection of an increasingly expansive understanding of what architecture could be.

When it comes to housing policy, we talk about something very dear to all of us—our homes. Now is a good time to review what we have already accomplished, and to detect the main shortcomings and obstacles but also the missed opportunities in developing the housing sector. The topic is discussed by the Head of Housing Policy of the Ministry of Climate Veronika Valk-Siska.

For many years, a dumb witness to the rich history and architecture of Narva on the wasteland bordered with Soviet brick apartment buildings, the Town Hall of Narva is about to be revived, Madis Tuuder accounts.

Why is it no longer possible for 21st-century Estonia to continue without a spatial development office, and what kinds of new values would the new office create?

Spatial design of a city is not a project with a clear beginning and end, but a continuous process, and a wickedly slow one at that.

We are asking how the European Union, local government and the architectural office can contribute to the development of architectural thought?

Life-centric approach in architecture and spatial planning may pave the way for more symbiotic relations between nature and the city.

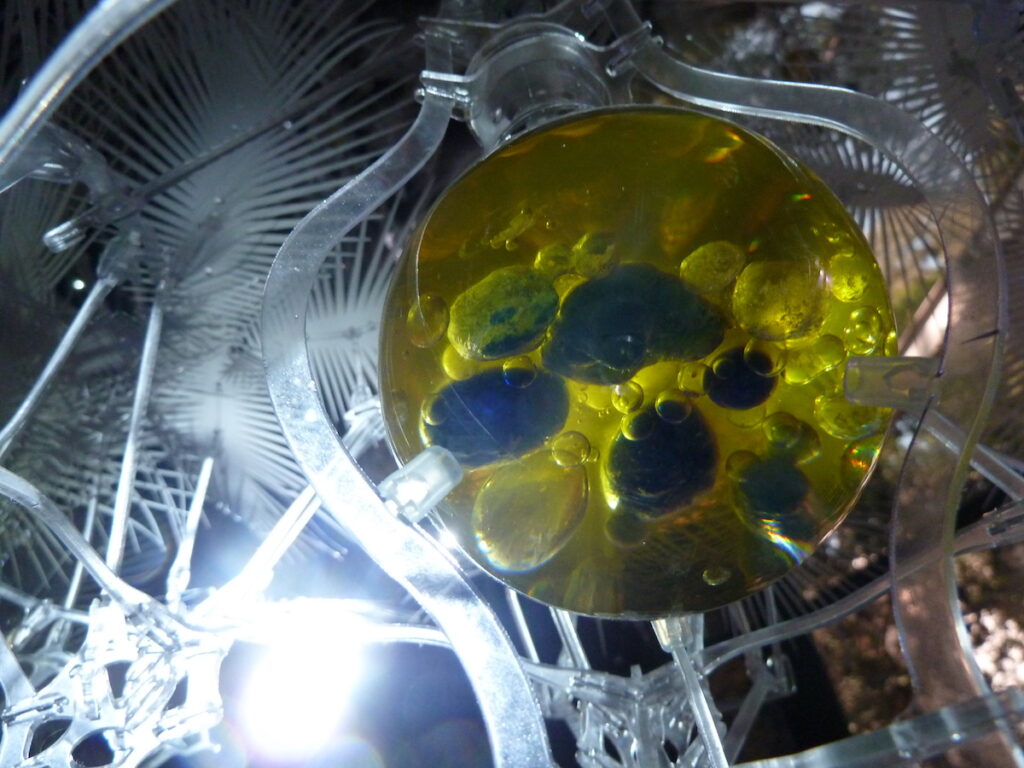

Smart cities are not merely for people and robots. Due to climate change and biodiversity decline, the combination of the physical and the digital is increasingly related to the needs of all species. Combining the natural and built worlds can be assisted by biotechnology, for instance, the use of bioreactors as a source of energy and by the smart application of landscape data in urban design, for instance, by means of biodigital twins or augmented reality. It shifts our perspective and poses the most critical and intriguing challenge of a smart living environment—how to adopt a life-centred rather than human-centred approach.

Villem Tomiste is like a figure from the beginning of 20th century Young Estonia movement – genuinely European, deeply urban, and as such, slightly suspicious for the local conservative community. Unlike many architects who preach social benefits, he actually lives by what he promotes in his civic visions – urbanistically to the core, commuting on foot and by tram, avoiding over-consumption, and with a refined aesthetic sensibility. Contemporary spatial culture is, for him, a field of opportunities: extending from urban planning and landscaping projects to dialogues with contemporary music, the visual arts and various exhibition practices.

No more posts