ARCHITECTURE

Suure-Jaani Gained a Chunk of a Town (centre) 〉 Toomas Tammis.

Fertile Architecture 〉 Karin Paulus

A Heated Sanctuary 〉 Kadri Roosi

Estonian Farmstead – a Compass Pointing to Both the Past and the Future 〉 Madli Maruste

Maschinenwerke 〉 Ott Kadarik

LANDSCAPE

A Travelogue of Mäetaguse 〉 Katrin Koov

Reviving the “Indutrial Backwoods” of Tudulinna 〉 Kaur Sarv

Small Town Hues 〉 Elo Kiivet

From the City to the Countryside 〉 Andres Rõigas

How to Make Villages Smart? 〉 Edith Wouters

A Glance at the Oslo Architecture Triennale 〉 Madli Kaljuste

Empty Coats 〉 August Krogan-Roley

TALLINN ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE

Beauty Matters Thanks to Faith in Human 〉 Kaja Pae

Space and Digital Reality 〉 Siim Tuksam

An Interview With Avatars 〉 Johan Tali

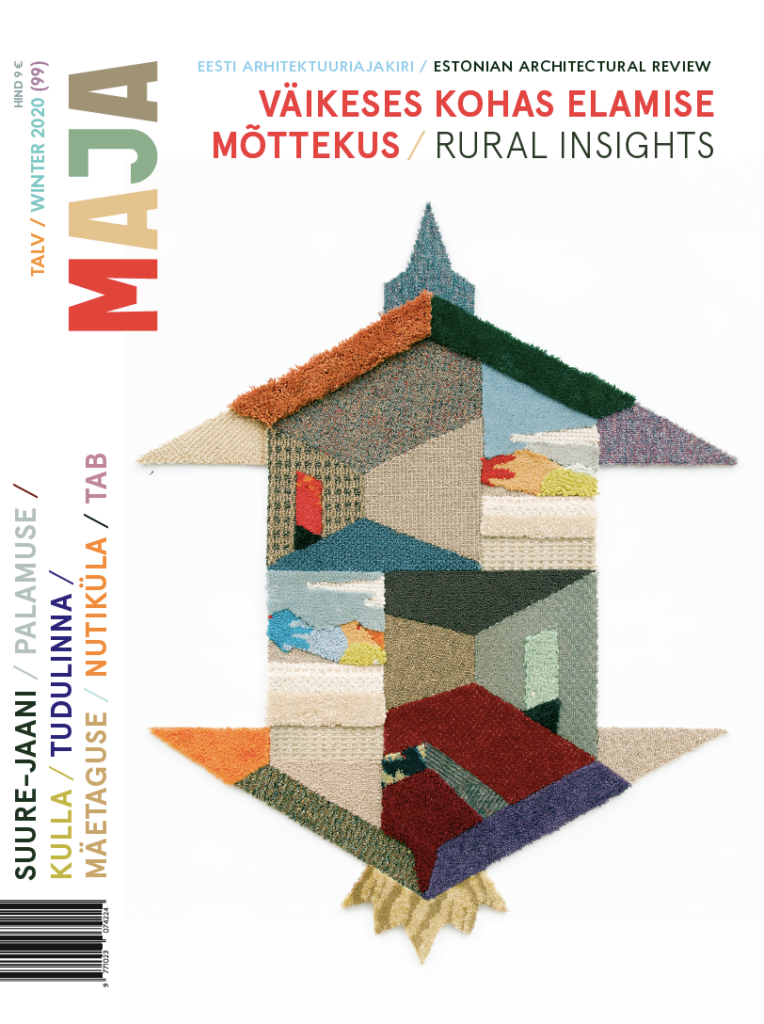

Rural Insights

Small Estonian boroughs and rural areas are facing similar challenges as numerous other European non-urban areas. The spatial policies of such places are mostly focussed on the phenomena accompanying the ageing and declining population. In case of shrinking small boroughs, the densification of the town, defining the central area and bringing public functions under one roof have proved a fairly functional solution. The impact of depopulation on spatial design was explored by Maja exactly two years ago.

Despite the objective problems, we have inadvertently adopted the rhetorics of absences when talking about small towns and rural areas and tend to compare them with larger places. But what are the unique values of small places? We will take a closer look at the most vivid examples of the architecture and landscape architecture recently created in places with small populations and the kindness provided to their users. What are the special features of these architectural examples and is there anything to learn from small places when dealing with larger ones? Or perhaps they carry values that would not even be possible in larger areas? Courage to experiment is often more common there than in cities. The church hill in Tudulinna represents a phenomenon of its own – the wooden church has lost its tower and the windmill its wings, but people still sense the unique quality of the place and aim to turn it into a small cultural centre.

We have set out to cover a number of public buildings and objects of landscape architecture that have been created and shaped on the initiative and in cooperation with the local people. One common feature of the new objects is their moderation – their sufficient size creates a sense of cosiness and comfort. They have particular accuracy and precise necessity about them and so it seems that nothing has been made for an average anonymous user. Every serious and in-depth spatial experience is preceded by an experience of cosiness.

The buildings made in small places also seem very fragile – it is mostly based on the work of one local person with vision and passion that can easily subside once the person leaves. The health centre in Suure-Jaani is a good example of a long and successful process with the comprehensive vision upheld from the search and conceptualisation of the location up to the construction.

In the context of population decline, we may ask if the objects built in the countryside at the moment stand for the so-called contemporary minimum or the contemporary archetype representing the current values and delineating everything that we are not willing to give up? Showing our bare soul? It is surprising how expressive these samples of (landscape) architecture built in small places can be in describing the modern times.

The last section of the issue is dedicated to Tallinn Architecture Biennale “Beauty Matters” focussing on beauty as a human decision criterion in design process and exploring the future relations between digital technologies, architecture and man.

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae

January, 2020